Lust, Lucre and Lunacy

The love triangle of Evelyn Nesbit, Stanford White and Harry Thaw ushered out the Victorian Era with a big bang. The trio’s tangled tale is, in fact, a thoroughly modern one, rife with powerful men behaving badly, abused women, tabloid headlines and way too many lawyers.

In 1901, Evelyn and her widowed mother migrate to New York City from Philadelphia, where the captivating teenager had been earning her keep as a model. She soon lands a part as a chorus girl in a Broadway musical, Florodora, and the plot thickens.

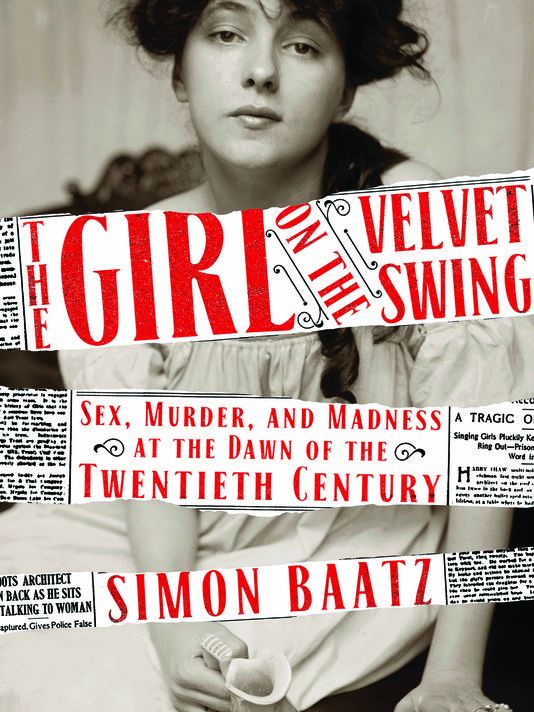

Historian and author Simon Baatz has resurrected a forgotten saga of lust, lucre and lunacy that would seem improbable if it were merely fiction. In "The Girl on the Velvet Swing: Sex, Murder, and Madness at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century," he ably recounts this topsy-turvy drama. No clues are necessary: Mr. Thaw kills Mr. White, at a Broadway play, with a pistol.

Stanford White is 47 and the acclaimed architect of Madison Square Garden when he spies Evelyn’s photo in the newspaper and invites her to his lair, where he pushes the 16-year-old back and forth on a velvet swing that hangs from the rafters. It is odd, to be sure, but he seems the perfect gentleman, and there is a chaperone.

White wins over Evelyn’s mother to the purity of his intentions with tales of his influence in the theatrical world and by paying the family’s rent and other expenses. He is simply a selfless benefactor, but not for long.

Before the summer ends, White rapes the 16-year-old. Evelyn does not report the crime, but several years later, and now married, she tells her husband, Harry Thaw, about the assault. He takes matters into his own hands. Evelyn’s graphic testimony at Thaw's murder trial makes for racy reportage, inspiring calls for press censorship. Even President Teddy Roosevelt confesses to reading every word.

Using memoirs, including Evelyn’s, and contemporary newspaper accounts, the author fleshes out the characters in novelistic fashion. The transcendent power of money and the vulnerability of women in society are on full display. Thaw employs some 40 lawyers in seeking his freedom.

It is a saga with few heroes but one heroine — Evelyn Nesbit. She is not simply beautiful, but also smart, talented and resilient. When wealthy men disappoint, she perseveres, pursuing a career as a film actress and cabaret singer. Countless come-hither photos of her survive on the Internet. With the odds stacked against her, she emerges as the prototypical single mother. (She had a son while her soon-to-be-ex-husband was confined to an insane asylum, and raised him by herself.)

Conversely, the filthy rich come off poorly throughout — including the murder victim, the murderer and Evelyn’s snooty mother-in-law — and this before that plague on plutocrats, the federal income tax. They all appear to be charm-school dropouts.

If the book has a flaw, it is that some key information and pertinent ruminations by the author that would have been welcome earlier are relegated to the epilogue and the afterword. That aside, this true-life theater is packed with action, surprises and a quasi-happy ending.