Margaret Mead et al

Franz Boas, a German immigrant, was the Pied Piper of modern American anthropology. More than a century ago, he taught his students at Columbia University to look at other societies, whether the Zuni of the American Southwest or South Sea Islanders, with an open mind.

Boas challenged his charges to shed their Western cultural baggage as they fanned out across the planet to document and understand how the rest of the world lived.

His followers and successors included the likes of Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict. The latter helped the United States government understand Japanese culture on the eve its occupation of that nation following World War II.

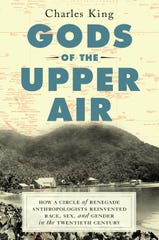

In his new book, “Gods of the Upper Air: How a Circle of Renegade Anthropologists Reinvented Race, Sex, and Gender in the Twentieth Century” (Doubleday, 448 pp., ★★★ out of four), Charles King follows the often eccentric lives of a handful of adventurous academics who trekked to isolated and oftentimes dangerous places to do their research.

In some cases, these globetrotting scholars established a society all their own. For example, Mead and Benedict were lovers, while Mead, who married three times, was known to have a boyfriend or a girlfriend (or both simultaneously) on the side.

More significantly, King ably documents the collective impact that Mead et al. had on how anthropologists and the public alike viewed their own and other cultures. Not everyone behaved like Americans, or wanted to, and some of the “primitive” people Mead and her colleagues studied and lived among clearly had things to teach “more advanced” societies. They disseminated their finding not only in research papers, but also in best-selling books, such as Mead’s “Coming of Age in Samoa.”

In Samoa, teenagers didn’t wax rebellious as they transitioned into adulthood and there was no juvenile delinquency to speak of. Sex was viewed more casually, before and after marriage, and occasional dalliances and same-sex encounters were common. In some cultures, women did the same work as men and the line of familial descent was matrilineal. These societies had figured such things out centuries ago.

What Boaz and his acolytes pioneered was the notion that there are myriad cultures and lifestyles, and that ranking them or arbitrarily separating humanity into categories based on nationality, ethnicity, gender, IQ, sexuality or religion is a mistake, sometimes a disastrous one.

Today, it is common to refer not simply to a country or society as having its own distinct culture, but also to smaller entities such as a company or a neighborhood, or even a sports team.

King points out that while these new “cultural anthropologists,” as they called themselves, were learning about non-western societies, the purported “advanced” nations of North America and Europe were proving themselves to be anything but enlightened. Never mind two devastating world wars; in the previous century, America was a bastion of the eugenics movement, which worked to prevent people deemed genetically unfit from reproducing -- by forced sterilization and other means.

African-Americans faced societal and governmental discrimination and Jews such as Boas, among other groups, also were victims of racial bias. Such practices were admired and expanded upon by Adolf Hitler.

The author, a professor at Georgetown University, succeeds in bringing Mead and her fellow travelers into sharp focus as they pioneered a new field and documented mankind’s many-splendored diversity in a positive, rather than a divisive, light.