Rick Bragg's Dog

In Rick Bragg’s world, pet owners don’t have to visit the pound to rescue dogs. The canines save themselves when they show up bloodied and bedraggled, with bits and pieces missing, exhausted at the end of dirt driveways. Two good ears would be an upset.

Bragg’s people dwell in the hardscrabble foothills of northeastern Alabama and have been collecting strays for generations. They don’t name dogs right off. The wanderers might be gone or dead by week’s end.

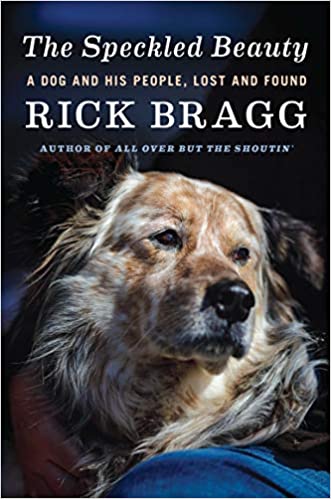

“The Speckled Beauty: A Dog and his People, Lost and Found” (Knopf, 256 pp., ★★★½ out of four) is the Pulitzer Prize-winning author’s latest foray into arcane southern mores. Speck, for short, is the family’s latest acquisition. Free range doesn’t do him justice. He is wild and crazy and incorrigible, harasses the livestock, attacks dump trucks and fights with fellow rescues, generally terrorizing his environs. He’ll stay in the house a whole half hour before he gets fidgety, perchance to roll all over a decaying deer carcass in the woods.

When a deliveryman asks the inevitable question, “Does he bite?” Bragg replies, “He even bites me.”

Bragg has done it again, focusing his lyrical prose on one aspect of his Southern roots while managing to embrace much larger terrain in the process. His cast of characters encompasses not just Speck but his 83-year-old mother, his brother Sam and enough barnyard and woodland creatures to populate a decade's worth of Disney movies.

No one in the family takes to Speck the way Bragg does, perhaps because both have been taking their lumps along the road of life. The continued survival of either is at question more than once in recent years. Both eat the same food, including collard greens and fried okra, cornbread, buttered beans and short ribs.

Meanwhile, Sam, the stalwart older brother, comes down with cancer, and his aversion to Speck softens a bit. He stops spitting on his head when he gets too close. Bragg is a master at merging misery and merriment. He tells his ailing brother that in his chemo fog he petted Speck. Sam shakes his head and replies, “That just doesn’t sound like something I would do.”

There is plenty of melancholia herein and while this may not be Bragg’s masterpiece, it still delights the senses and is as honest as the day is long. Bragg himself is in remission from cancer, and in his 60s is living in the basement of his mother’s house. He is seeing a psychiatrist, breaking an unwritten code of Southern machismo. He writes: “We do not go to therapy. We do not talk about our feelings, unless it includes a quart of Wild Turkey, or a case of Pabst Blue Ribbon, and then we mostly cry about our daddies.”

In the face of all of the above, Bragg launches his first solid laugh line by page three – and his prose can make the hair on the back of one’s neck stand up: “I know this is reading a lot into a dog who falls asleep in his food bowl, suffers shivering apoplexy when you rub his belly, and acts as if every wayward possum is a sign of the end of times. But I don’t think any dog knows home better than the one thrown away once already.”