Twitchell and Twain

They were an odd couple, to be sure, the Rev. Joseph H. Twichell and Samuel L. Clemens. The Connecticut Yankee pastor, Yale 1859, ministered for nearly a half-century to the upscale congregants of Asylum Hill in Hartford. Clemens, the wild and irreverent frontier satirist better known as Mark Twain, was a late convert to Hartford (1868) and dubbed his friend's sacred calling "the church of the holy speculators."

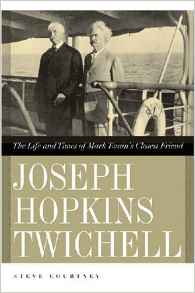

Yet friends they became, fast and for life, in myriad and wonderful ways that would be most difficult to duplicate in our frenetic, cynical society. This remarkable friendship and the life of the good reverend is the subject of a new book, "Joseph Hopkins Twitchell: The Life and Times of Mark Twain's Closest Friend" by Steve Courtney.

Joe and Mark often would walk the eight miles from Hartford to Talcott Mountain and back again, talking like boys playing hooky. And while these odysseys were healthful, they weren't about lowering cholesterol. Bucolic ruminations would run from war and politics to literature, family, friends and life everlasting.

When Clemens died in 1910, his friend recalled him at a Carnegie Hall memorial service thusly: "The impressions of Mark Twain that rule my thoughts of him were acquired in the intercourse of the fireside - his and mine - in the converse of a great many long summer afternoon rambles and in travels at home and abroad that we shared, in the close companionship of which we usually slept in the same room, often in the same bed, and hundreds of times - as I trust it is not amiss for me to recall here - said our prayers together."

Looking down (or perhaps up), Clemens' concern about Twichell's affectionate remarks would have been that the reverend had drafted him - from beyond the grave, no less - to be a Christian soldier.

Always the skeptic, even on his knees, Clemens came to view religion less kindly late in life. In a candid missive to Twichell in 1909 — one of a series that were not intended to be delivered so that the author could write freely — Clemens challenged a hallowed Christian practice:

"Joe, where is the fairness in the missionary's trade? His prey is children. . . . Would you be willing to have a Mohammedan missionary do that with your children or grandchildren? . . . 'Do unto others, etc.' is a Christian sarcasm, as long as Christian missionaries exist."

Twichell well knew what his friend thought about God and man. Clemens wrote him in 1902: "We don't know any more about morals than the Deity knew about astronomy when he wrote Genesis."

As important as this remarkable relationship is to Twichell's biography, the book is first and foremost about the minister. Clemens appears in full only midway through, and Twichell's own life and times were nothing to sneeze at.

Courtney has ably mined all the available sources, including his subject's journal, sermons, books and letters. A longtime writer and editor for The Hartford Courant, Courtney brings a wealth of local knowledge and obvious passion to the task. The book grew out of an article he wrote for the late Northeast magazine in 1996.

Like any good journalist, Courtney knows what to lead with. In 1858, as a junior at Yale College, Twichell and two classmates were returning from dinner when they faced off against a larger group of local firemen. Such "town-gown" confrontations were not uncommon and sometimes turned violent, even deadly. Each college boy was packing a pistol. In the melee, shots were fired, and one person died.

Nonetheless, Twichell graduated on time and, having had his "conversion experience" before college, set his sights on becoming a Congregational minister. It was a time of great moral ferment, as America wrestled with the issues of slavery and rebellion.

A Lincoln Republican, Twichell supported John Brown's abortive raid at Harper's Ferry. When war erupted, he volunteered to minister (although not yet ordained) to a regiment consisting largely of rowdy Irish Catholics. His duties involved assisting at gruesome battlefield surgeries, and the war's terrible carnage tested his belief in God's plan.

In 1865, Twichell ascended to the ministry of Asylum Hill Congregational Church, a position he would hold until 1911. He married, fathered nine children and watched a modest provincial city transformed over the decades. He would nudge his conservative flock toward good works, charity and acceptance of new arrivals who were not so fortunate - and who seemed so very different from his spiritual charges, Hartford's WASPish business and cultural elite.

Courtney paints an engaging and thoroughly researched portrait of a man who, although born 170 years ago, seems modern in so many ways. His ecumenical and social inclusiveness was well ahead of his era.

But make no mistake, his times were different from ours in ways great and small. Consider these two tidbits: Twichell and his fellow Elis in 1859 were required to attend prayers twice daily, the first session commencing at 6 a.m. In 1878, Twichell assisted at the birth of his sixth child, but the following month he went tooting off to Europe to pal around with Clemens for two solid months.