Beer that Made New Haven Famous

http://www.courant.com/new-haven-living/food-drink/hc-hm-nh-hulls-march-20150303-story.html

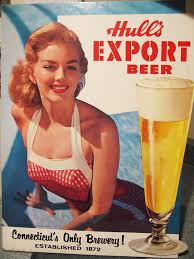

Back in the 1970s, Hull's Export was the freshest beer for miles around. It was brewed in New Haven, and despite the name it didn't travel far. Why would it? It was doing fine close to home. From the Hull Brewery at 820 Congress Ave. it was a hop, skip and a jump to Jocko Sullivan's on Chapel Street.

"On St. Patrick's Day, we'd move 100 kegs at Jocko's," says Richie Cahill, who managed Hull's draft systems in bars throughout the state. "I'd set them up early and then help them drink it. A 12-ounce glass was 25 cents. Back then you'd have a shot and a beer. You could get a six-pack of Hull's Export for under a dollar. A case was $3.15."

To provide some perspective: 100 kegs is more than 3,000 gallons of beer: in one bar, on one day, OK, a pretty special day, but still ...

Cahill, who is 66 and lives in New Haven, began working for Hull's in the 1960s, when its draft beer was holding its own against invasive lagers like Schafer and Rheingold. Most local bars had only one draft tap back then and Hull's was the local brew. Case closed.

Hull's fresh products, among them Bock Beer, India Pale Ale, and Cream Ale, had another advantage. They were crafted from the complex waters of the legendary "Lost River," a mineral-rich freshet that still flows beneath the former brewery site. Beer, after all, is 90 percent water, and Hull's water was reputed to journey south all the way from the verdant hills of New Hampshire. "The water we used was the best," says Cahill, who estimates that back in his day Hull's brew crew totaled 100 people, many of Irish and German extraction. Cahill himself hails from County Kilkenny. They would all lose their jobs in 1977 when Hull's closed after a run of 105 years.

Hull's demise also spelled the last gasp of beer brewing for a generation in New Haven, a city once hailed as the Milwaukee of the East Coast, according to Jeff Browning. Browning is a beer historian and the longtime brewmaster at Bar on Crown Street. "New Haven had 28 breweries before 1900," he says. "There were five or six on Crown Street alone."

Hull's was the last one standing, and standing tall, according to a 100th anniversary supplement that was published in the New Haven Register in 1972. The company reported business was brisk and that it was producing close to its brewery's capacity of 150,000 barrels a year. To translate: Hull's was making about 4.5 million gallons of beer and ale per year for its thirsty Connecticut clientele, or 12 pints for every man, woman and child in the state.

In a letter to his employees and the public, company President Edward H. McGann, another son of Erin, wrote, "Over these years, loyal men, some with 35 to 40 years service, fathers, sons, and grandsons have worked here to produce what we consider to be the finest glass of beer that can be brewed."

Five years later the bottom fell out.

Longevity alone makes a good case that Hull's was at least crafting the finest beers and ales in New Haven even before it became the only major brewery in the city in 1933 – and later the only one in Connecticut when Cremo Brewery in New Britain folded in 1953. By then Hull's was settled into its Congress Avenue digs, which had been the home of Philip Fresenius' brewery from 1852 until the onset of Prohibition in 1920.

By the time the national ban on booze ended in 1933, it had stimulated organized crime but had rung the death knell for public spirited companies like Fresenius' and virtually all of the remaining New Haven hops purveyors, among them: breweries named Quinnipiac, Lion, Yale, Staehly, Weibel and Rock. Hull's acquired Fresenius and reportedly stayed on its feet during those 13 dry years by making ice and non-alcoholic malt beverages.

Beer, of course, has always been more American than apple pie. The Mayflower had dozens of barrels below decks, and one of the reasons the Puritans settled on Plymouth rather than proceeding to Virginia, their original destination, was that their "victuals being much spent … especially our beer." The home brews in the New World tended to follow English traditions but often with substitute ingredients for malt, which was hard to come by. Spruce shoots or ground ivy tended to give these early concoctions a bitter taste.

Being what H.L. Mencken termed "ombibulous" by nature, Americans turned to hard cider to get happy. But beer would make a comeback in the mid-19th century with the influx of German immigrants, such as Philip Fresenius, whose forte was crafting and imbibing fine Teutonic lagers, lighter in color and smoother than English-style ales. It was during this heady period, in 1872, that Col. William Hull opened up shop; the company, whose brewery was then located where the Trumbull Street connector to I-91 now runs, was sold in 1912 to George Jacob and Michael McGann, whose descendants ran it until the end. Hull's may be gone, but beer still rules: accounting for 85 percent of the alcoholic beverages consumed by Americans.

By the time Hull's celebrated its 100th birthday in 1972 there were fewer than 100 breweries left in the United States, where once there had been some 2,000, and omnivorous national brands were circling the regional survivors. "The big breweries would come in and undercut the smaller regional ones," Browning says. "For example, they would pay for new draft systems if the bars would agree to only sell their draft beer. Their national ads pitched the concept of sameness. If a beer was national it had to be better, and it followed that the local brews had to be inferior. In the 1950s and '60s brands like Budweiser were doing for beer what McDonald's was doing for food."

Richie Cahill says that competitors like Ballentine, which was being hawked on TV by New York Yankees broadcaster Mel Allen, wanted Hull's out of the picture. "We were keeping the price of beer down," he says. "We were moving kegs for $15; that's more than 15 gallons of beer for $15. We were shipping hundreds of kegs of Hull's Export a week to the Rockaways [in Queens, New York]."

Advertising by bigger brands and the changing beer culture would eventually diminish Hull's reputation. Its provinciality, its vat-to-tap intimacy, which today is such a point of pride for craft brewers, began to work against it. If Hull's Export didn't taste quite the same as flashier brands from cosmopolitan cities, there must be something wrong with it. One slander that made the rounds in the 1970s, Browning says, was that the water Hull's drew out of the ground beneath Congress Avenue was tainted by formaldehyde leaching from a nearby cemetery.

If Hull's wasn't up to snuff toward the end, Browning surmises, it was more likely that the company was economizing on the quality of its ingredients, or perhaps trying to dumb down its brews to taste more like its nondescript competitors. Cahill adds that as competition was increasing Hull's infrastructure and aging machinery were breaking down more often.

Michael McGann, who is the son of the last president of the Hull Brewing Company and a Hamden resident, worked there summers during college and after graduation until 1973. He points out that Hull's had become a distributor for other brands, like Schlitz, that were invading its turf. It was one way to cushion the blow of increasing competition, but it also took time and resources away from its own products. Then the Arab oil embargo struck in late 1973. "The cost of everything, like energy and grain, went up and then inflation really took off, and things got more and more difficult to manage," he recalls.

Browning says that when Hull's shuttered its doors the sprawling Congress Avenue plant was awash in unsold cans and bottles, payroll records, promotional items and the like. "That's why there's so much Hull's material for sale online," he says. "They never threw anything away. A 1934 Hull's can sold for $12,000, but you can get Hull's Export cans from the 1970s for under $10. The brewery was loaded with them, even after the fire in 1978."

The fire put an exclamation point on Hull's epitaph. It was gone and it wasn't coming back. New Haven would henceforth be importing its beers and ales. Gone but not forgotten, Hull's Export was a craft beer before craft beers became really cool.

Richie Cahill still has some Hull's artifacts, including a few cans and trays. But his memories are more valuable. "It was fun working there, a lot of work, but a lot of fun, too," he says, adding with a laugh, "You couldn't beat the fringe benefits."