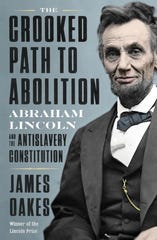

Abe & Abolition

Both Abraham Lincoln and the institution of slavery were eminently complicated. Lincoln hated slavery but he was not an abolitionist, according to Civil War historian and author James Oakes in his latest book, “The Crooked Path to Abolition: Abraham Lincoln and the Antislavery Constitution” (Norton, 288 pp.).

And remarkably, neither the word slavery nor its derivatives appear in the United States Constitution, which both pro and antislavery proponents cited prior to 1860 as backing their cause. The enslaved are referred to euphemistically as “persons” who are “held to service.”

Words matter. Slaveholders would argue that the Constitution guaranteed their property rights and that slaves were chattel, while antislavery proponents would point to the words “persons” and "liberty" in the founding document.

Lincoln was a lawyer and a politician, and he sought to use the law, including the Constitution, as well as his political gifts, to advance his anti-slavery agenda. In the end, he was more successful than the abolitionists, whose soaring rhetoric he deemed unhelpful to forming a more perfect union.

In “The Crooked Path to Abolition,” Oakes delineates early on the many things that Lincoln was not: “He never called for the immediate emancipation of the slaves… he never denounced slaveholders as sinners and never endorsed the civil or political equality of Blacks and whites… He never opened his home to fugitive slaves… he endorsed voluntary colonization of free Blacks… He certainly spoke at colonization meetings… but never at an abolitionist meeting.”

Oakes ably guides the reader through the Byzantine legal labyrinth of slavery American style – perhaps Gordian Knot is a better metaphor. If the author’s narrative occasionally waxes repetitive and academic, all is forgiven: Most often Oakes brings clarity and insight to a political conundrum of bewildering complexity.

In the beginning, in 1788, when the Constitution was adopted, there were 13 American states, all permitting the enslavement of human beings.

But there were stirrings of emancipation. The Constitution, whose preamble touted the “Blessings of Liberty,” banned slavery from American territories and empowered the federal government to ban the importation of slaves in 1808 – which it did that year.

But slavery did not wither away, as many of the Founding Fathers –including slaveholders like Thomas Jefferson – had hoped it would. In fact, the institution became more entrenched where it existed, and the debate over its future more contentious.

The can that was kicked down the road in 1788 landed, in 1861, at the feet of Lincoln, who was very clear that he was not in favor using the federal government to ban slavery where it existed. The Constitution left that power to the individual states. Indeed, during his lifetime, his home state of Illinois, a free state, passed laws discriminating against free Blacks, including their rights to move into the state, vote, marry, or serve on juries. That was perfectly legal, too, until the Constitution was amended following the Civil War.

But Lincoln was dead set against the expansion of slavery and in favor of using the lawful power of the federal government to limit the practice to places where it already existed. In 1849, as a U.S. Congressman, he introduced a bill to abolish slavery in Washington, D.C., a federal district. It failed.

As adamant as the slavocracy remained, time and history were not on its side. On the eve of the Civil War, free states outnumbered slave states 18 to 15. During the war, three more free states joined the union: Kansas, West Virginia and Nevada. In 1864 Arkansas abolished slavery, the first state to do so in 60 years. By the close of the Civil War, there were 27 free and nine slave states, just enough to change America’s founding legal document to ban slavery and extend civil right to Blacks, in theory anyway.

As Oakes points out: What was inconceivable in 1960 was feasible in 1865.