Fighting the Good Fight

In 2008, seven years after America invaded Afghanistan in the wake of 9/11, it was a largely forgotten war. George W. Bush’s administration had diverted its attention — and much of the nation’s military resources — to Iraq, where a second war was not going well.

But in remote sections of Afghanistan, aptly named the “Graveyard of Empires,” American soldiers still were being tasked with holding forbidding chunks of real estate, battling insurgents, and winning the hearts and minds of local residents.

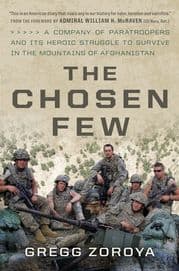

"The Chosen Few: A Company of Paratroopers and Its Heroic Struggle to Survive in the Mountains of Afghanistan" is about one such godforsaken place and the sacrifices made there by some 150 Army soldiers from “Chosen Company.” It is a remarkable story, whose telling raises myriad questions without resorting to polemics. It is unlikely that those who read it will ever utter the phrase, “Thank you for your service,” quite the same way again.

"The Chosen Few" (Da Capo Press, 370 pp., ***½ out of four stars) is a gripping, exhaustively reported account of modern warfare: The GIs versus the Jihadis. Author Gregg Zoroya — a veteran USA TODAY war correspondent, and now a member of its editorial board — cuts through the fog of war by drawing on numerous sources, among them hundreds of interviews with participants and their families, official postmortems, and videos of the action taken by soldiers and insurgents alike.

Zoroya delivers the adrenaline of combat right to the reader’s easy chair. His prose is direct and clear, and never upstages the action. He also brings the warriors to life, chronicling their trials and triumphs before, during and after three searing firefights. Some are wounded and fight on. Some die horrific deaths. Astounding bravery is commonplace. Be prepared to flinch.

Chosen Company, circa 2008, was a motley crew of mostly very young men, or “lost boys,” as the author dubs them. Many hailed from broken homes and troubled pasts, and the Army provided not only a challenge and an escape hatch, but also a surrogate family.

Ryan Pitts, who never knew his father, joined the Army at 18. Four years later — riddled with shrapnel and unable to walk or fully use one hand — Pitts gathered what weapons he could, crawled to a defensive position and fought on, fully expecting to die, either from loss of blood or enemy bullets.

Pitts was the last man alive in Topside, a makeshift observation post high above an unfinished base in the remote village of Wanat. Its residents had fled, leaving their houses as cover for the insurgents to use. They had neglected to tell the Americans of the impending attack. The local police, though they feigned innocence later, took part in the assault. It is unlikely that the hearts and minds of these people were winnable from the get-go.

The inevitable question is why the Americans were there in the first place, in the remote Waigal Valley. Previous attacks had led them to abandon two nearby posts, and, like them, Wanat was vulnerable, flanked by mountains that provided ideal cover for attackers. The Army abandoned the base three days after the deadly assault.

Zoroya doesn’t take sides. He lets the facts and comments of others fall where they may. Pitts was not among those who blamed higher-ups, whether in his company, in Kabul or in Washington. He didn’t see himself as a victim.

In a remarkable statement, reflecting a sentiment shared by many of his brothers in Chosen Company, he said, “It’s crazy to say, but I had some of the best times in my life with those guys in Afghanistan.”