Behind the Lines

Virginia Hall was considerably more than simply an American spy. She was, to be sure, a crackerjack infiltrator, first for the British and later for her own country.

But she also was a guerrilla leader fighting the good fight against Nazi Germany four years before the allies landed at Normandy in 1944. She had been fighting Hitler for nearly two years when her country backed into the war in Europe after Pearl Harbor.

Her status, if long overlooked in the history of World War II for her contribution to the liberation of France, was well understood at the time by Klaus Barbie, the Gestapo leader known as the “Butcher of Lyon.” She was atop his most-wanted list, and, if captured, a horrific death awaited her.

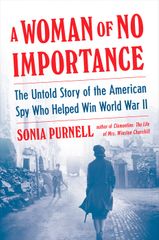

In "A Woman of No Importance: The Untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II," Sonia Purnell resurrects the compelling saga of a remarkable woman whose persistence was honed early on by her battles against low gender expectations and later on by her disability: she had a wooden leg.

The author, a British journalist and biographer, brings into focus the dramatic struggles behind enemy lines that hastened the liberation of France and saved thousands of lives. Her subject had to worry not simply about the Nazis but also their many French collaborators and condescending – and sometimes incompetent – male colleagues.

Purnell’s research is thorough, and she ably places Hall in the context of her times: women risking their lives in battle would remain controversial for more than a half century after her exploits. There is much high drama, and the book has been optioned for Paramount Pictures with Daisy Ridley slated for the starring role.

Nothing seemed to get in the way of Hall’s desire to make more of her life than simply “marrying well,” as her mother expected her to do. Twice rejected by the American Foreign Service despite speaking multiple languages, she was an ambulance driver at the front in France in 1940 when the British recruited her for the newly formed Special Operations Executive, an organization whose mission was to “set Europe ablaze” by a variety of means – some of them gleaned from tactics used against the empire by the Irish Republican Army.

James Bond had nothing on Hall. Licensed to kill, she sported pens that shot poison ink, cyanide pills, dangerous loaves of bread (when sliced), and exploding horse dung set out ahead of German convoys.

There was, however, a decided lack of glamour to the real deal. Before being deployed on a second tour in occupied France, this time by her own country’s Office of Strategic Services, Hall needed a new look to avoid capture. As part of her extreme makeover – from an attractive 38-year-old journalist to an aged peasant – “she has her fine, white American teeth ground down by a much-feared female London dentist to resemble those of a French countrywoman,” according to the author.

Clearly here was a woman on a mission.

That she was so remarkably successful was something of an embarrassment to some of her less-accomplished male colleagues. That she had not until now received her due may be attributed to a corollary to the maxim that history is written by the victors: it most often has been written by men.