Ben and George

It would be difficult to conjure what the United States of America would have become without George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. One can argue it might have been stillborn. Such is the impact that these two men had on the Revolutionary War and its aftermath.

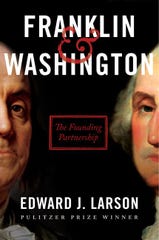

“Franklin & Washington: The Founding Partnership” (William Morrow, 352 pp., ★★★½ out of four) by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Edward J. Larson, is a dual biography that examines the decades-long relationship of these two remarkable patriots, who put their lives and fortunes on the line to create a nation.

Washington was first in war and the presidency. The expectation that he would be the new nation’s first chief executive inspired skeptical delegates to sign the document that established a more viable federal government at the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. Franklin’s efforts helped that eventuality as well.

Before that, while Washington was leading American soldiers for eight years, without leave or pay, in the Revolutionary War, Franklin was in France persuading its monarchical government to help the upstart colonists defeat King George III. It is hard to imagine America winning the war without French military, material and financial support.

France’s loans to the colonies – in total, more than $60 million in today’s currency – that Franklin negotiated are less well known than the battlefield exploits of Rochambeau and Lafayette, but the infusion of cash was critical to the cause. It turned out that Americans were not simply against taxation without representation: They were against taxes, period, including those desperately needed to prosecute the fight for independence.

For more than three decades – from 1754, when they were loyal British citizens during the French and Indian War, until Franklin’s death in 1790 – the duo assisted one another, corresponded and periodically met, most often to ponder critical matters of state.

Drawing extensively on the work of other historians, Larson presents a concise yet engaging narrative that illuminates how individuals can have as much impact on events as broader societal or economic forces.

The author also is good at seasoning his work with compelling details and delicious trivia. For example, Franklin was a sometimes vegetarian who wrote newspaper columns under the gender-bending byline of Silence Dogood. His illegitimate son was the royal governor of New Jersey whose loyalty to Britain never wavered.

Washington gratefully accepted the help of accomplished Prussian military officer Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, who arrived at Valley Forge “with a young male companion” and was widely suspected of being gay, Larson writes. Washington was ahead of his time in adopting a policy of “Don’t ask, don’t tell.”

Washington, however, was on the wrong side of history when it came to slavery. He lost the battle to exclude enslaved or free blacks from the fight for freedom. Larson writes that a tenth of the Continental Army eventually consisted of black soldiers. Franklin, on the other hand, had freed his house slaves by 1787 and presided over a Pennsylvanian abolitionist society.

When Washington called on Franklin at his Philadelphia home at the start of the Constitutional Convention, he walked rather than traveling by carriage, which would have entailed arriving with a retinue of slaves.

Washington already seemed to have seen the handwriting on the wall regarding human bondage. During the war, the British offered freedom to slaves who would leave their masters and join their forces; many did, including 17 from Mount Vernon. Washington wrote of this trend: “There is not a man of them, but would leave us, if they believ’d they could make there escape."

He added, “Liberty is sweet.”