Born Again & Again

When she was growing up in Missouri, hard by Route 66 and in the shadow of the Ozarks, Susan Campbell was completely immersed in that old-time religion. In fact, she took the full-body plunge twice to make sure she got it right.

She noticed early on that you could never tell for certain if you had this religious business right. There were so many rules, prohibitions and great expectations. Thank you for not dancing, for one.

The author went to church three times a week, and the Sunday morning service was a three-hour marathon. Summers she attended church camp.

In her family’s eventual house of worship, the church (yes, lowercase “c”) of Christ, she was taught many things. Women were to keep silent in the assembly. It said so in the Bible.

Boy, did they have the wrong girl. At 10, she was rewriting divine scripture, punching up the parts that women played and selling the result to her grandmother for cold cash.

When one of Campbell’s older brothers ascended to the pulpit at the tender age of 12, she should have been happy for him, but she wasn’t. The highest level a grown woman could aspire to was the title of “baptized believer.” They let her teach Sunday school, but not to pubescent boys. They told her that she couldn’t instruct boys once they reached 12 years of age, just the girls. So she stopped teaching Sunday school.

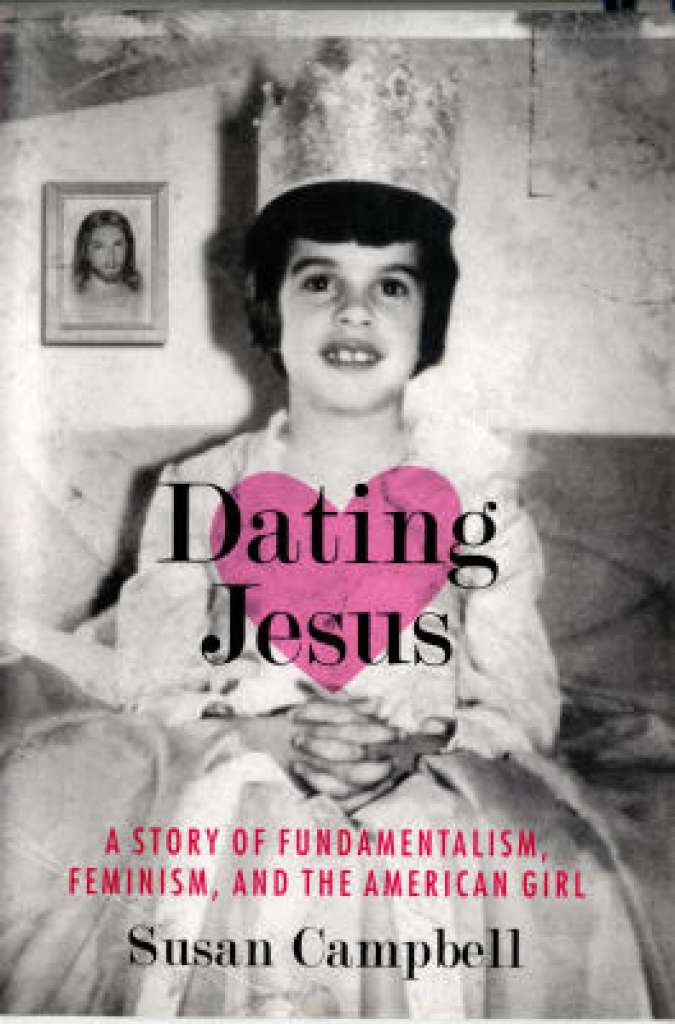

"Dating Jesus: a Story of Fundamentalism, Feminism and the American Girl" is a mesmerizing, funny, impressionistic memoir of a spiritual and thoughtful person, one who has spent her life wrestling with religion, the meaning of faith and her feelings for the Divine. In her first book, Hartford Courant columnist Susan Campbell has not come to bury religion. She is trying to understand it and the effects it has had on her and on others. (She gives credit where credit is due, such as the myriad good works that churches brought to bear in New Orleans after Katrina.)

The process of discovery involves not only her life experiences but also intermittent discourses on religious history, Biblical scholarship and politics. Unlike many devout people, she knows her Bible, chapter and verse.

In straightforward, down-to-earth prose, Campbell stalks her past like a prizefighter cutting the ring in half before launching short, telling jabs. To inflict punishment, she is willing to take her lumps as well. After fleeing north to Connecticut, and now churchless, she returns to Missouri for a visit with her brother. They attend services with his new “religion lite” congregation. There are instruments (gasp), clapping and even some swaying. Most tellingly, the parishioners appear blissfully happy.

“The treacly sweet love of God coats everything here like cotton candy, and I hate myself for thinking that way,” she writes, adding a bit further along: “I know I am mean and judgmental, but this religion doesn’t seem real to me if they feel so damn happy about it.” As she starts to cry, her brother, who is now simply a congregant himself, says to her, “Fundamentalism broke off in us, didn’t it?” She writes in reply, “Yes, it did. Like a sword, fundamentalism was plunged into our bodies, and then it got broken off in us so that we will never, ever heal from the wound. Like Perpetual Jesus on the Perpetual Cross, we are the walking wounded.”

All is not pain and anguish, however. The author recalls with fondness experiences like “knocking doors” for Jesus, going house to house soul searching. And once she even gets one gentleman half-converted to the True Way before he backslides.

But the effort isn’t about the destination; it’s about the quest, about the big one that always gets away: “Bagging a Methodist would be nice, but a Roman Catholic — or a Jew, if we could find one! — is even better ... with Catholics’ bells and smells and standing up and sitting down and rote memorization of man-made words? Now that’s a soul.”

As Campbell goes to the mat with organized religion, her tag-team partner is none other than Jesus Himself. She still loves him, and to untangle her life, to find out who she is, or should be, she has to figure out who the real Jesus is. In her amply footnoted ruminations on the true meaning of the Christ, Campbell is at her best. Besides caring for the sick, the poor and the dispossessed, Jesus, she insists, was a feminist.

Though relegated to lowly status akin to slaves or children, women felt comfortable with Jesus, approaching him, talking with him, following him. And he felt comfortable with them in return.

He consorted with harlots, touched a woman who was bleeding, drank from a Samarian woman’s water jug and spoke with women as he spoke with men. As even the disciple Paul, known for his misogynistic musings, conceded, “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Jesus Christ.”

Jesus had come to change everything, Campbell asserts, or at least to try like hell.

It is enough to make a lapsed Catholic cry.