America's Veeps

The federal office of the United State Vice President is one of those rare human creations that is difficult to libel. Before lowering himself from Senate majority leader to accept the post, Lyndon Johnson termed it a "part-time job." Thomas R. Marshall, Woodrow Wilson's inept understudy (a Hoosier, like our current veep) described it this way: "[The vice president] is like a man in a cataleptic state: He cannot speak; he cannot move; he suffers no pain."

When Vice President Marshall did manage to speak, he often said the wrong thing, prompting The New York Times to rail in 1915: "If Indiana cannot raise men of presidential caliber, she should at least try to train them to keep silence . . ." This is still good advice.

The most telling comment on the office, however, is that it has been vacant 16 times for a total of 37 years, almost one of every five in our constitutional history, and the nation has neither cared nor suffered.

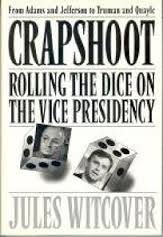

Jules Witcover, Evening Sun columnist and veteran Washington reporter, is the author of "Crapshoot: Rolling the Dice on the Vice Presidency" with help from a colleague, Jack W. Germond. They do a workmanlike job of recounting the evolution and intrigues of this peculiar institution, from John Adams to J. Danforth Quayle. Mr. Witcover's immediate inspiration for this opus is obvious, although the current vice president is just the latest in a long tradition of dismal second fiddles. Spiro T. Agnew was chased from office because of evidence that he took bribes both before and after Richard Nixon made him his running mate.

Mr. Nixon himself was not exactly a household name when, at the tender age of 39, he was paired with Dwight Eisenhower in 1952. Twenty-two years later, the Nixon-Agnew double disgrace should have been a wake-up call to the nation: Let's be a little more particular about the second-stringers we nominate and vote for.

Unlike the last century, when nonentities like Hannibal Hamlin served for a term and then disappeared into political hyper-space, this century has seen the No. 2 spot become a stepping stone to the Oval Office. Of the last nine presidents, five (Truman, Johnson, Nixon, Ford and Bush) first served as veeps. Since 1900, 16 of our 20 vice presidents have actively sought the top job.

It is remarkable, however, that while the post has clearly become more significant -- if only as a degrading means to a lofty end -- the people who are chosen to run for it have not improved in caliber. The head of the ticket, who almost always picks his understudy nowadays, will insist that Alexander Throttlebottom is presidential timbre; in reality, we are often presented with splinters, also-rans plucked from obscurity, like William E. Miller, for narrow political purposes. Remember him? No? Don't feel badly. There's no reason to.

Even more mainstream choices, like Geraldine Ferraro or Robert Dole, don't pass muster either. A third-term congresswoman, Ms. Ferraro was hardly a national figure with the sort of varied experience necessary to lead the nation. She was chosen, of course, for other reasons. Mr. Dole may have had the requisite credentials on paper, but his temperament was far from presidential. During his 1976 debate with Walter Mondale, his opposite number, he responded bitterly to a reporter's question about Watergate by describing the nation's four major conflicts in this century as "Democrat wars" that resulted in 1.6 million American casualties. His stunning vituperation may have cost Mr. Ford the election.

So what's an electorate to do about this national disgrace? Arthur M. Schlesinger has proposed that we simply eliminate the office. He argues that the original intent of our Founding Fathers was not to have the vice presidency evolve as it has, particularly as the automatic replacement for the president. A vice president was supposed to take over the president's duties if need be, but not become the president himself. He blames this historical misunderstanding on sloppy prose in the 1789 document and on John Tyler's forceful assumption of power in 1841 upon the death of William Henry Harrison just one month after his inauguration. If we need a new president, Mr. Schlesinger proposes that we simply hold an election while a cabinet member baby-sits the office.

Mr. Witcover has another perfectly rational solution to our "second banana" affliction: Have the president-elect pick his helpmate after the election -- subject to congressional oversight, as is the case with appointments to the cabinet. Of course, we Americans will do nothing unless presented with a crisis, a crisis like President Quayle.