Elvis, Elvis, Elvis

The very title—“Dead Elvis”—is liable to inspire a laugh, but this book is no joke. At one point the author, Greil Marcus, likens Elvis to the white whale in "Moby Dick." Remarkably, this is not a joke either.

Marcus, who has written on pop culture for publications like Rolling Stone and the Village Voice, takes Elvis very seriously, as perhaps well he should. Like many other Americans, his initial reaction to the first coming of the King of Rock 'n' Roll in the late 1950s was ambivalent: "He was thrilling, but he was also weird, and I kept my distance."

After Elvis' comeback in 1968, the author began getting closer to his subject. In the years since he has frequently written about Presley, and many of the essays in this collection are based on articles that first appeared elsewhere. The point of pulling them all together is to document and analyze the late Elvis' third comeback, which began over a year ago and is going strong. Like virtually all things Elvis, no one knows why Elvis is suddenly everywhere again.

To quote the chorus from Mojo Nixon's 1990 hit ballad "Elvis Is Everywhere:" "Elvis, Elvis, Elvis, Elvis, Elvis, Elvis," etc. At one point Mojo has Elvis in the Bermuda Triangle and sings: "Elvis needs boats." (He apparently got them because he sure hasn't disappeared.) The question is do we need another book on Elvis, one that spends a good deal of space dissecting other books on Elvis?

Marcus' point is this: The King may not be gaining weight anymore, but we simply won't let him die—some of us more than others, of course, but never mind. More significant than the startling phenomenon of the living Elvis, the highest paid dead entertainer on Earth, is the notion that before we let him rest we have to understand him. That may take quite a while yet.

Just exactly who was this guy? Why did so many of us flip for him? (Even the ones who didn't know more about Elvis than they do about the Constitution.) And why won't he go away? He sang songs that no one knows the meaning of to this day—and a whole bunch didn't have any meaning—and it was as if he invented the cure for cancer and polio and showed us how to turn tin cans into Cadillacs in our basements.

The first thing we noticed about Elvis was his body. As Marcus puts it, his movements were characterized by "the absence of constraint." Black rhythm and blues singer Bo Diddley noticed. After Elvis' death, he told a radio interviewer of his initial reaction to Presley: "He's doing my legs." Elvis was doing a little bit of everything: country, blues, schmaltz, but it is far from clear that he was specifically copying Diddley or anyone else. After all, he claimed his idol was Dean Martin.

Rather, it seemed as if he absorbed diverse elements the way a sponge will suck up different liquids and make a new concoction. Some argue that Elvis didn't understand some of the blues songs he sang—the ones that were understandable. Who knows what Elvis understood? One thing is clear: He could sing. He didn't sing white and he sure didn't sing black, not the way many white artists have mimicked black music since.

When Elvis first walked into Nashville's Sun Records in 1953, to pay to record a song, he was asked "Who do you sing like?" Elvis replied, "I don't sing like nobody." Maybe Elvis knew more than he's been given credit for. Marcus believes his subject was conscious about what he did, a calculating actor who knew he had something unique to put across.

When he strolled onto the stage of the Ed Sullivan Show, when he strolled into our living rooms, cocky as you please, he smiled a smile that said he knew folks were screaming all over America, knew others were squirming, knew it was a little silly, but, shoot, here I am. I'm what all the fuss is about.

Damn, Elvis was flat-out cool. Thermometers don't measure low enough for early Elvis. Yet in 1956, on Ed Sullivan, he was already a parody of himself—and he knew it. Elvis, my friends, was the first Elvis impersonator. It was already way too late to just be himself.

Elvis would absorb America, all its good and terrible impulses, and become lost in our adulation. The stories are now part of our collective memory: drugs, orgies, gunplay, Cadillac gifts, binges upon binges. Early Elvis was late Elvis in no time.

It is the one question that this book doesn't address: how long are we going to be reading, talking and thinking about Elvis? Like so many things Elvis, no one has a clue.

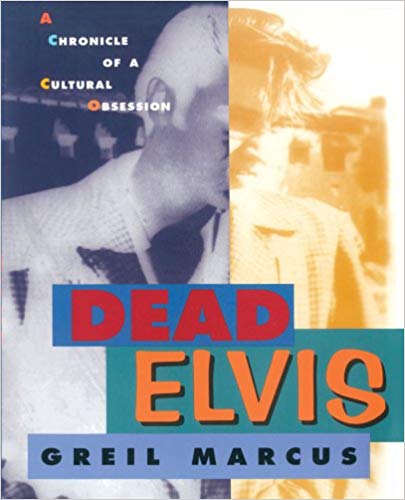

Marcus' book is worth reading for its subject alone, for its moments of inspiration and insight. The illustrations are first rate, often hilarious: images of Elvis as seen by others. Marcus himself is a bit too much at times, his chapters sometimes hard to follow. One gets the impression that the author thinks about Elvis everyday, when every other day would do nicely.