Escape from ISIS

By Jackson Holahan

When violence becomes as routine as it has in Central Asia and the Middle East over the past decade and a half, only the most sensational and gruesome acts tend to warrant inclusion in the daily headlines. The rise of ISIS has been catalogued in detail by both its savvy internal social media arm as well as the mainstream media. Both publish videos exposing the ghastly acts of torture and violence that have come to define the group to the wider world.

The ISIS propaganda machine broadcasts a coordinated digital message that serves as a valuable recruiting tool. The distribution power of the internet has given rise to an unsettling phenomenon few people predicted; Large numbers of Europeans and North Americans are radicalized in their home countries, pledge loyalty to ISIS, and serve its will, whether on the battlefields of Syria or in support of the group’s widening operations abroad.

Dimitri Bontinck, a court officer in Antwerp, experienced ISIS’s international reach firsthand. His son Jay was radicalized by the charismatic leader of a local Islamic organization. In early 2013, Jay left Antwerp and made his way to Syria, where he joined an outfit of Dutch and Arab fighters who were one of the earliest Syrian groups to align themselves with ISIS. Jay left without a trace and, worse yet, would not respond to any messages or calls from his parents.

While desperately scouring the internet in search of his son, Bontinck spotted Jay in a video standing alongside several Dutch fighters in a Syrian field. Bontinck knew that he had to bring his son home or risk never seeing him again. He headed to Syria before the week was out.

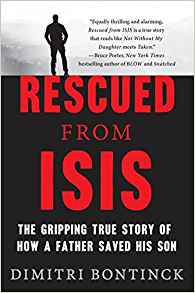

In "Rescued from ISIS: The Gripping True Story of How a Father Saved His Son," Bontinck recounts the harrowing journey to find his son. Bontinck describes his odyssey into the heart of ISIS territory with an urgent, staccato ring. You can almost picture him jotting down notes while bumping across dusty roads to the next meeting that will hopefully lead him closer to Jay.

Bontinck’s dogged persistence ultimately succeeds, after three separate trips and an exhaustive number of meetings. The very fact that Bontinck escaped with his own life, and that of his son, is amazing enough. That he did so without any knowledge of Arabic or any pre-existing contacts in Syria in the midst of a war zone is miraculous.

Bontinck accepts every meeting or call, be it with a journalist, jihadi, or any number of the opportunists who thrive in the ungoverned space of war zones. Bontinck’s success is perhaps dependent upon the power of the father-son connection that resonates with nearly everyone he encounters on his quest.

Bontinck is a unique character, and it is hard not to admire a man who took such drastic efforts to recover his son. Upon returning to Belgium with Jay, who was prosecuted and imprisoned for joining a terrorist organization, Bontinck realizes that his situation is not unique. He is barraged with calls from parents whose sons have left their European homeland for the battlefields of Syria. Their parents beg him to help. Unable to say no, Bontinck returns to Syria a number of times and leverages his network to bring their children home.

Bontinck’s days in Syria are now over, but he continues to worry about the lure of radicalism for today’s youth. He believes many Western countries are hesitant to admit that a problem even exists. Furthermore, Bontinck astutely illustrates a trend in which governments are not only slow to take preventive measures but also are unwilling to provide the rehabilitative steps necessary to integrate reformed jihadis back into society. He worries that the alienation Jay and others like him feel upon returning home will not be assuaged by societies that refuse to embrace and employ them. He’s right. We’ll need more than the bravery of one man to upend a societal epidemic that shows few signs of abating.