Melville's Inspiration

It isn’t known if the 72 enslaved Africans aboard the trading ship Tryal — among them eight newborns — were aware of the successful conclusion of Haiti’s long slave revolution that year, 1804, as they rose up and took control of the ship.

The captives had already endured a yearlong ordeal. They had been taken in chains from their home in West Africa by British slavers. Their ship was then captured by a French privateer (a Marseillaise-singing Jacobin no less), who sold them to a Spaniard who marched them across South America and over the Andes and put them on another ship bound for Lima, Peru.

Their 53 days of freedom aboard the Tryal were cut short by an American ship captain who made sure they would be sold back into slavery in Lima. This act freed him from mounting debts incurred during his disastrous voyage hunting nearly extinct seals.

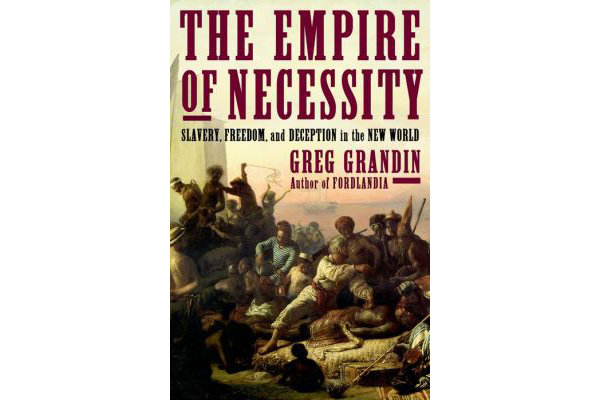

In "The Empire of Necessity: Slavery, Freedom, and Deception in the New World," Greg Grandin has chronicled the historical event that inspired Herman Melville to write the novella “Benito Cereno” in 1855. Grandin goes one step further, however, by making Melville one of his book’s leading figures, alongside the slave leaders Mori and Babo, the seal hunter Amasa Delano (the American captain who returned the slaves to captivity), and Cerreño, the hapless Spanish captain of the Tryal.

The author of “Fordlandia” and a professor of history at New York University, Grandin has written a gripping, lavishly researched account of high seas drama, as well as the trials of the slaves before and after their revolt. Equally fascinating is the thesis Grandin advances: that in 1804 human political liberty and abject bondage were both rising apace – often advanced by the very same people. It wasn’t so much irony as cause and effect, the author argues.

Slavery made the modern world, the argument goes. Slaves provided cheap labor, of course, but also substantial collateral for business investment, profits for insurance companies, and a potent stimulus to expanding global trade.

Grandin points out that the “peculiar institution” actually boomed after 1776: “Of the known 10,148,288 Africans put on ships bound for the Americas between 1514 and 1866, more than half were embarked after July 4, 1776.” In 1805, there were fewer than a million slaves in America: Within four decades there would be nearly 4 million, worth in aggregate “more than all of the capital invested in railroads and factories” in the United States.

Paralleling the historical drama is an equally intriguing examination of how Melville transformed the incident into fiction for his own metaphysical purposes at a time when debate raged in America over slavery. By 1855, most nations around the world had done the right thing and freed their slaves, including all of Spain’s former colonies in South America.

Grandin argues that scholars over the decades have had great difficulty grasping Melville’s meaning, failing to see that he is writing about bondage and freedom at a time when his country is on the cusp of the violence that will finally settle its own argument over slavery.

Until fairly recently, says Grandin, the slave leader Babo had not been viewed by most literary critics as a symbol of people yearning to be free, but rather as pure evil, the embodiment of man’s worst impulses.

A common theme uniting the historical and literary strands of this narrative is the inability to perceive reality. When Delano first boards the Tryal, he can’t conceive that the slaves have taken charge and are sophisticated enough to perform an elaborate theater to fool him. Instead, he believes the clearly distraught Cerreño, who, with Babo fairly glued to his side, insists that nothing is amiss, even though his captives are roaming freely about the ship.

Delano – and Melville’s early readers – may not have grasped it, but the Babo of “The Empire of Necessity” is smart, disciplined, and resolute in the face of privations and imminent death. Thanks to Grandin, his story has become both heroic and compulsively readable.