Broadway Joe

It is hard to think of Joe Namath without smiling. He is an American original, a flesh-and-blood natural who shone at any sport he took a shine to and guaranteed a Super Bowl win when his team was an 18-point underdog. He’s a total dude. He’s Broadway Joe.

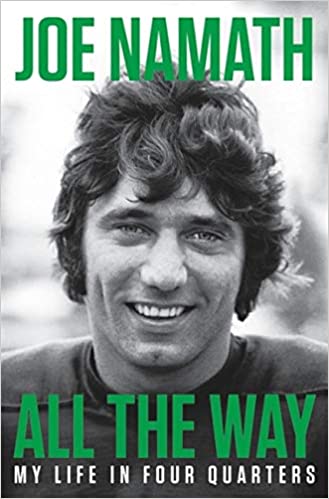

But make no mistake: the gifted athlete is not a natural author. This unmistakable fact, already known to the reader, is conceded in the "about the author" section at the end of Namath's meandering memoir, “All the Way: My Life in Four Quarters” (Little, Brown and Company, 240 pp., ★★★ out of four).

It begins: “Joe Namath has been a reluctant author since he was able to write.”

But let it go. Joe has stories to tell, and with the aid of Sean Mortimer and Don Yaeger, he does better than a passable job. His (their?) prose has a certain appeal, as in: “I hated all winds, unless I was flying a kite or they were coming at my back.”

Namath played the field in simpler times: quarterbacks called their own plays; players chain-smoked in the locker room at halftime; beefy linemen didn’t lift weights; and concussions were considered just another no-count boo-boo.

That was then (a half-century ago). Now, the author writes, without elaborating on his tantalizing declaration: “With the help of hyperbaric oxygen therapy, I still have mental access to many of my past experiences.” Such revelations come at random intervals between the author’s reliving, on film, Super Bowl III in 1969, when he led the upstart New York Jets to an improbable victory over the mighty Baltimore Colts.

Here’s another revelation: Namath, whose best friend since kindergarten is Linwood Alford, an African-American, was surprised to learn upon arriving to play football in Alabama in 1962 that the university was segregated.

He was in the crowd the following year as Gov. George Wallace stood in the doorway in a failed attempt to block the admission of two black students. Namath writes that he admired the courage of Vivian Malone, who endured Wallace’s tirade and would become the school’s first black graduate in 1965. He also admired the Crimson Tide’s legendary football coach Bear Bryant, who the author acknowledges would not give a scholarship to a black player until 1971.

The book deals cursorily with such substantive issues, leaving the reader hanging at times. He writes that his father disciplined him on occasion by taking a belt to his backside; when he was 14, the two argued and didn’t speak again for two years. But the author doesn’t linger and soon returns to the safer ground of playing fields.

The reviewer, however, doth protest too much. Even casual sports fans will find this an enthralling read. For all his flaws – and the author does not hide them – Namath is a likable and lively raconteur.

What’s more, his is a remarkable life. He not only beat the Colts, he whooped alcoholism, evolved into a doting grandfather and endures the many side effects of gridiron fame with nary a complaint.