The Human Sideshow

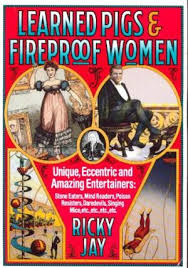

Connoisseurs of "stupid pet tricks" and aficionados of "idiot savants" must acquire Ricky Jays book. For the rest of humanity, "Learned Pigs and Fireproof Women" is prescribed as an antidote for Mondays. This is an account of some of the most astounding novelty acts in show business history, written by a man who can throw an ordinary playing card higher, harder, faster and farther than any human being ever. Step right up . . .

Marvel at pig-faced women who ate out of silver troughs, possessed fabulous dowries and could grunt in several languages (Marvel, too, that there were no pig-faced men). Let the "Human Aquarium" of the man who supped on stones expand your sense of wonder. Ponder, too, the indescribable feats of that musical Frenchman, "Le Petomane."

But, first, consider learned pigs: alias porcine prophets, sapient sows, or sagacious swine. In the 18th and 19th centuries such amazing pigs told time, read minds, solved math problems, and even elucidated the "Irish problem." These pigs did not go unnoticed by Samuel Johnson, who observed: "a race unjustly calumniated . . . we do not allow time for his education, we kill him at a year old." Indeed, the highbrow breed packed houses and even regaled kings and heads of state. Second billing in the acts went to such known draws as "turtles that fetched."

Turn now to Blind Tom, who, although apparently a complete and utter idiot, could play most tunes on the piano after hearing them once. Born to slavery in 1853, Tom was apparently the real McCoy. Complicated scores, such as Beethoven's Third Symphony, took him longer to master, but he would then stand up, turn around and play the piece behind his back, flawlessly.

Jay`s opus is a compilation, generously illustrated, of historical stage sensations. His prose is seasoned with occasional explanations of the miracles. The book suffers from trying to cover too much, including mention of numerous individuals who did essentially the same routines. Still, the author -- himself an accomplished sleight-of-hand artist -- leads his audience through the horde of bizarre entertainers who combined both physical skills and trickery to bedazzle and bewilder. Jay concludes: "People are fooled today in the same way and by the same things that fooled them four or five hundred years ago."

Like a true trouper, the author saves the best for last. Or perhaps putting the tale of Joseph Pujol, known as Le Petomane, at the end is bald symbolism. In any event, the dapper Frenchman had an unusual gift. He could make the sweetest music come from the most unlikely place on his anatomy. His melodies would drive audiences into spasms of laughter. A late 1800s press report stated: "Many fainted and fell down and had to be resuscitated."

Oh, yes, Le Petomane did impressions, too. Shall we leave it at that?