Macabre Artistry

These persevering artifacts dot the landscape, here and there, in clumps, reminders of a time and a people long passed. Where else but in New England can you walk up and touch something hand-crafted by the first generations of Europeans on this continent? No climate control, no docent or admission, no rope barrier. History is there for the touching and reading, right there on a tablet — a stone tablet.

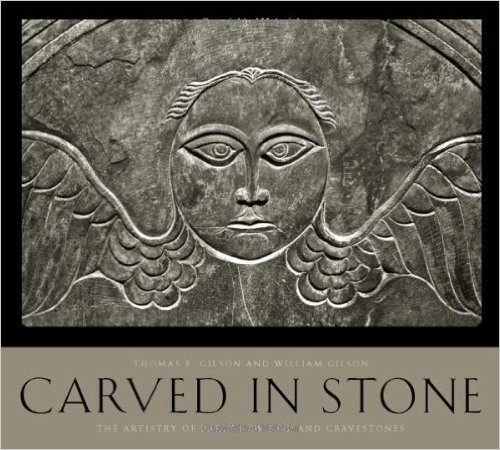

These solid chunks of the past are strange and wonderful, irresistible and repellent, sign posts to our past as well as our future. There's never a crowd. Above ground that is. If a case can be made for visiting these lonely, eerie, open air exhibits, two brothers, Thomas and William Gilson, have made it in their new book "Carved in Stone: The Artistry of Early New England Gravestones" (Wesleyan University Press, $30). Born and raised in Connecticut, the pair developed a fascination with graveyards independently, and only became aware of their shared obsession later in life. William, a University of Connecticut grad, is the writer. Thomas, who attended Southern Connecticut State University, is the photographer. He has taught black-and-white photography courses and has a previous book to his credit, "The New England Farm."

William, whose essay begins the reader's ghoulish odyssey, describes the technique his brother employs in many of his more than 80 photographs of gravestone art dating from 1640 to 1810: "By filling the frame of the picture with a single face and thus removing for the moment all the accompanying symbols, and by patient and very careful attention to the sunlight, Thomas has made the faces appear as if caught in an instant of human expressiveness. Some flicker of emotion seems to be occurring, as if the creature in the stone is trying to make contact."

This infernal inference would be particularly disturbing at dusk, so the recommendation here is to visit your local, ancient, and seemingly forgotten cemetery in glorious sunlight. There's one not a half mile from my house, where ship captains and Revolutionary soldiers and children and a lone Mohegan Indian are buried. None died in this century. Someone keeps the place up: I can't imagine whom. I find visiting it a welcome break from my frenetic, multitasking life. If you are too, too busy for that, the next best thing would be to read the Gilsons' book. There is no plot and the ending is obvious from the start. But the words and the images are compelling, and it does a body good, now and then, to think about that thing that is awaiting us all at the end of the road.

Q. You point out that because the austere faith of Puritans and Pilgrims forbade graven images, the development of the art form that you celebrate in the book is something of a mystery. Could it be simply that, as with Arthur Miller's salesman, Willy Loman, "attention must be paid"?

William: In the absence of direct documentation, words from the carvers themselves explaining the origins and motivations for their work, mysteries remain.

Thomas: I'm not certain the Puritans viewed the carving of gravestones as an art form. It was a paid job for someone with a specialized craft. They are similar to revered objects recovered from ancient burial grounds throughout the world that are now placed in museums for the whole world to admire. Similarly, these gravestone images have become for us works of art.

Q: The photographs in the book are focused on the art — on the faces, skulls and skeletons — largely excluding the epitaphs. My favorite from graveyard visits is "She did the best she could." Do you a memorable one or two that you each can recall?

William: One of my favorites from the period is "Gone Home."

Thomas: There are many variations of this common epitaph: "Remember me as you pass by/As I am now/So you must be/Prepare for death/And follow me."

Q. What is it about your upbringing or nature that has drawn you to your fascination with gravestones?

Thomas: We grew up in rural Connecticut and our parents were Congregationalists. We always visited the family gravesite after Sunday services; it was just part of our lives. I've always felt comfortable in graveyards. When I joined the Navy, to my surprise, my tour of duty included being in the National Honor Guard and burying the dead at Arlington Cemetery. That seems somehow relevant to my eventual interest in early New England gravestones.

Q. Is it healthy?

William: Yes.

Thomas: Many people are uncomfortable in graveyards and attach extreme sorrow and fear to them, but I find solace there. I'm always mystified by the stone carvings as well as the place itself.

Q. Have you ever lingered in graveyards after dark?

Thomas: No, not after dark.

Q. Along with oddness and grimness, you ascribe whimsy and even humor to some of the artwork that you include in the book. Are the carvers mocking death, or religion, or the departed, or what?

William: At least some of the carvers were first rate artists and among artists there will be mockers and jokers of various sorts. Some of the stones certainly reveal a sense of humor.

Thomas: I've never thought about any of the carvers mocking anything … From the carvers' perspective it was a very serious endeavor. However, it is difficult to know. These images create an unanswerable mystery.

Q. Do either of you believe in life after death?

William: I don't.

Thomas: I cannot imagine non-existence.

Q. Interspersed among the photographs are excerpts from preachers and divines, such as Jonathan Edwards, whose sermon, "The Eternity of Hell Torments," is not recommended for the squeamish. What do you make of him?

William: That sermon is remarkable for its thoroughness; he allows not the slightest microscopic crack for escape from punishment. To modern sensibilities he can seem somewhat crazy, but we should remember he meant to scare his listeners away from sin.

Q. What will a leisurely sojourn in an ancient cemetery do for a person: why is it a good idea?

William: Quiet, birds, grass, trees, absence of litter, stones with beautiful carvings, poignant reminders of mortality – all good for you.

Q. Have you thought about what will appear on your final markers?

William: Yes: "It Was Interesting."

Thomas: I have not.