Madison Revisited

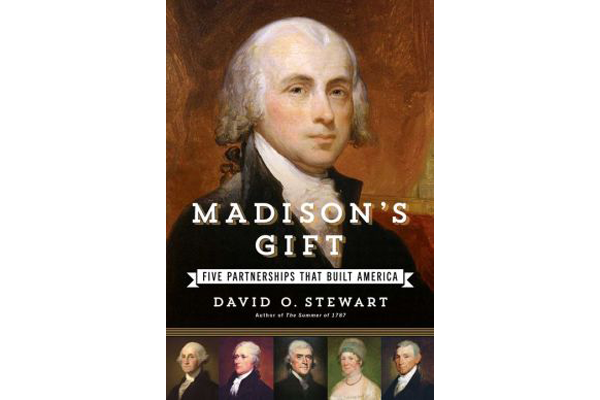

James Madison, our fourth President, is making a comeback nearly 180 years after his death. In the past six months a pair of books has chronicled his myriad contributions to his country. The more recent, and the better of the two, is David O. Stewart’s "Madison’s Gift: Five Partnerships that Built America."

The author tracks the Virginian’s career through his personal and political relationships with five other important historical figures: Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and, of course, Dolly Madison. That’s quite a network and Madison took full advantage of friends in high places.

His first major collaboration is with Hamilton, a brief and businesslike campaign that was instrumental in the creation and ratification of America’s Constitution, without which it is unlikely that 13 disunited states would have evolved into a great and enduring nation. There was talk of secession in 1787, not merely among states but within them, too. Northern and southern New York talked of splitting up. Madison was 36 when he helped to pull this national rabbit out of a hat, and if he had retired to Montpelier then and there, his legacy would be secure.

But he did not retire. Instead, he proceeded to help George Washington create a functioning government based more or less on the Constitution, while serving in the lowly House of Representatives but acting like a prime minister in all but name. This was Madison’s Federalist phase, when he feared the ineffectual anarchy of individual states more than the potential tyranny of an empowered central government. If the Constitution was a bit vague in spots – for example, on whether or not the President could fire cabinet members without Senate approval (which was required to install them) – Madison came down on the side of implied executive powers.

Stewart sums up his subject’s state of mind in 1787 succinctly: “Madison did not fear, he wrote, giving the president too much power: ‘I see, and politically feel that that will be the weak branch of the government.’ His expectation proved true thought the nineteenth century; the massive growth of executive power in the twentieth century was beyond his imagining.”

Later, Madison would join his close friend and fellow Virginian Thomas Jefferson in fearing the burgeoning federal government, switching sides in the tug of war between Washington, D.C. and the provinces. This ideological realignment would estrange him from both Hamilton and George Washington. Madison opposed the former’s plan for a national bank only to see Washington sign the bill. Two decades later, as president, Madison came to appreciate the value of Hamilton’s bank and would support its continued existence. It seems that even Founding Fathers flip-flopped now and then.

Jefferson and Madison - fellow plantation and slave owners, intellectuals, and political allies - had what might be termed today a “bromance.” They discussed everything from tobacco yields, architecture, and slavery to national security and the latest books, which they would purchase for one another on their respective travels. When they were apart, they wrote one another almost constantly. Together they created the first American political party in opposition to Hamilton and his fellow travelers, pioneering the partisanship that is so prevalent today. For example, they put a prominent journalist on the federal payroll whose job description was to write articles savaging the opposition.

While they would be termed strict constructionists today, President Jefferson and Madison, then Secretary of State, did not let Constitutional qualms get in the way of a good deal: buying the Louisiana Territory from France for four cents an acre. It is to their credit that in this case they didn’t let rigid ideology get in the way of common sense. On another front, ideology did interfere with political reality when President Madison – who disdained big government, including a robust military – led an ill-prepared nation to war against Great Britain in 1812.

Mostly, however, Madison and Jefferson got things right, and Stewart describes this dynamic duo as “the most influential political partnership in the nation’s history.” Starting with Jefferson in 1801, Virginian Republicans would dominate the national government for six consecutive presidential terms.

Madison’s relationships with James Monroe and with his wife Dolly are interesting, if not quite as compelling as the others. But throughout his fifth book, Stewart manages to bring the times and the characters he is covering vividly to life. His prose is clear and his insights are illuminating. His section on slavery telescopes the national debate down to the level of personal relations between founding fathers like Madison and Jefferson and the slaves they inherited, and would pass on to their heirs.

Slavery, indeed, was the ultimate partisan dilemma, whose solution eluded the best and brightest for fourscore and seven years. After the 1787 miracle at Philadelphia, perhaps another was too much to expect, even from the likes of Madison and Jefferson.

Stewart is a lawyer who doesn’t write like one. He weaves vivid, sometimes poignant details throughout the grand sweep of historical events. He brings early history alive in a way that offers today's readers perspective – although perhaps also, occasionally, a sense of chagrin.

Here, for instance, is Stewart's description of how the early American government functioned: “In that first Congress, floor debate featured men who prepared their own remarks, attended House sessions, and listened to each other. Few other activities competed for their attention while each chamber was in session. Committee work was performed at other times, while fundraising events and media opportunities were not yet invented.”

For readers in 2015, such lines may be surprising, but they serve as a useful reminder that much has changed in Washington, and not all for the better.