Mitch Albom and God

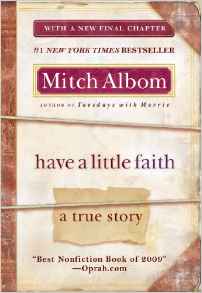

In his latest sure-to-be bestseller Mitch Albom, author of “Tuesdays with Morrie,” describes his growing involvement with two men of faith: his Rabbi from the old neighborhood, Albert Lewis, and the Rev. Henry Covington, former convict and drug dealer turned evangelist at a down-and-out inner city congregation.

Albom, a longtime sports columnist for the Detroit Free Press, is surprised when his eighty-something Rabbi asks him to do his eulogy. Although the author returns home to his New Jersey temple periodically, generally on High Holidays, it is largely out of nostalgia.

He is even a little put off by the request, wondering “Why me?” He has wandered from the regular exercise of his faith, which he has come to view as a vestigial, if quaint, appendage left over from his youth.

Besides, he only knows Rabbi Lewis in the distant, formal way that people tend to relate to clerical personages. To do the eulogy, Albom will have to get to know more about the stooped and ailing person who once stood so tall between him and God.

The eulogy-building sessions began in 2000 and stretch into eight years. They discuss all the great questions of the cosmos. What is happiness? Is there really a God? Can we prove it? Or disprove it? Why doesn’t God answer our eminently reasonable prayers? Why so much pain and suffering in this world?

While the author is getting to know his Rabbi, he is also forming a parallel relationship with Rev. Covington and his ragtag congregation in the tumbledown (literally) church called I Am My Brother’s Keeper. The two meet as journalist and story subject: what exactly is this mountain of a man up to in his outsized house of worship with the big hole in the roof? Albom’s initial skepticism of the preacher eventually evolves into admiration. Outwardly different in so many ways, Rev. Covington and Rabbi Lewis, have much in common.

In addition to bestsellers “For One More Day” and “The Five People You Meet in Heaven,” Albom has written six books on sports and several plays, hosts a daily radio in Detroit, and is a panelist on ESPN’s “The Sport Reporters.” A pianist, he performs in the Rock Bottom Remainders with Stephen King, Dave Barry and Amy Tan, and has founded several charities. He talked with me by phone.

Q. Have you settled on the reason why Rabbi Albert Lewis asked you to do his eulogy?

A. No, I think that is one of the great mysteries of the thing. I have always wondered that. I even wondered when I walked up the steps to do it. He did say once that he felt that a clergyman could in some ways best be evaluated by a member of his congregation. I’m still not sure why it had to be me.

Q. Could it be that you represented a challenge to him, you being the archetypal lapsed believer who grows up, moves away, marries a Christian, becomes successful, gets really busy, and wanders from the faith?

A. The prodigal son, huh? Well, it could be. I sometimes have thought that he sort of knew that by asking me he was going to get me to start coming to visit him. Maybe he felt he would slowly start pulling me in again. If that was his plan it worked.

Q. Was he a fan of your work? Had he read “Tuesdays with Morrie”?

A. Actually, not only did he read “Tuesdays with Morrie,” which he really liked, but he read the manuscripts for “Five People You Meet in Heaven” and “For One More Day” because I was working on those during the time I visited him. They became the basis of some of our discussions.

Q. I got the impression from the book that you came to the conclusion that believing in God can be very helpful to some people, like Rev. Henry Covington, who need help, and that was as good a reason as any for them, if not you, to believe in God.

A. I think if I say it can be helpful to other people I have to say it can be helpful to me. I don’t think I ever doubted a belief in God. I never became an atheist or an agnostic. I became an apathetic, just to stay in the “a” family. I wandered away out of laziness and lack of need. I had the belief in God, I just wasn’t doing much with it. I think it’s about believing that there is something bigger than we are, and then believing that everyone has a piece of that in them, a piece of divinity, of being a creation of God, then you feel a sense of being united with other people. It should be unifying. It’s not just about believing in something, it’s believing in other people.

Q. You write that beginning with Adam, people have tended to hide or run from God. Aren’t they in many cases simply running from religion, as you did?

A. I think a lot of people run from God because they don’t want to live up to any standards. You’re right, there are a lot of churches that are bad news. There are synagogues that are bad news, there are cults that are bad news. None of that makes God bad news or faith bad news. You shouldn’t run out of fear of believing in something bigger than you.

Q. You wrote that at one time you viewed religious customs as “sweet but outdated, like typing with carbon paper.” How do you feel about them today?

A. I don’t anymore. That’s some of the cynicism I had that has just washed off of me. There is something beautiful in some of these customs. It’s not like I’ve become ritualistic since, I don’t want to claim that I have. It’s not like all of a sudden I’m growing long sideburns or lighting candles on every occasion and the rest. But I don’t look at it cynically anymore. The symbols are about connecting with the people who did it before you.

Q. Have you returned to the faith of your youth?

A. In some ways. I was so adamant back then it would be hard to. I was going to school and being indoctrinated in religious studies three hours a day. If I ever returned to that I probably wouldn’t be on the phone with you. For the years I was visiting with Rabbi Lewis and writing the book, I had to do a lot of studying and re-reading Biblical verses and the rest of it to be prepared for my discussions with him and Henry. It reintroduced me to a lot of things I had let go. I go to Temple when I’m in New Jersey, and I go to church a lot at Henry’s. I haven’t changed my religion, but I feel very comfortable there. It gives me a place to pray.

Q. How has your everyday life changed – what you do, what you think about – as a result of your relationship with Rabbi Lewis and Rev. Covington?

A. It has made me more comfortable talking about faith. I used to bite my tongue when the subject came up. I didn’t want to talk about mine, and I really didn’t want to hear other people talk about their faith. I just wanted it to go away. The book has changed all that. Everyday I’m talking about faith and religion now. I feel now that it’s an important subject. I also feel much more of a kinship with people. I don’t think I realized that when you are breaking down the world into different faiths, that when people are of a different faith you don’t really feel like you can associate with them, I think I was shutting out a lot of the world in terms of getting involved. What I’m doing through my charity with the homeless shelters in Detroit, a lot of that is being done through Christian church-based groups. I think that’s fine, they’re doing good work. I have broadened my world.

Q. If you could talk to God and get a straight answer, what would you ask?

A. I presume it would be a straight answer. I think what I would ask, “Is it true that we have everything inside of us to make the world perfect and we just haven’t figured it out yet?” If he said “yes” I think I would live with much more hope.