Mobster Whitey Bulger

For a long stretch while he was on the lam from 1995 to 2011, James "Whitey" Bulger had to be content as the FBI's second most wanted man. Osama Bin Laden topped the list. But thanks to Navy Seal Team 6, in early May 2011 Bulger graduated to the top spot. The man who led Boston's Irish mob for decades and who secretly helped the FBI decimate his ethnic rivals in the Mafia, murdered dozens of people — many quite innocent and some with his bare hands — had a final exclamation point on his resume of crime.

Thanks to the FBI, which astonishingly had nurtured his murderous career for years, Bulger was certified as the bad-est man in America, at 81 years of age no less.

Bulger held the title for less than two months. On June 22, 2011, Whitey and his girlfriend, Catherine Greig, were arrested in Santa Monica, Calif., where they had been living two blocks from the Pacific Ocean in a rent-controlled apartment. Until that day, crime had pretty much paid for Whitey. He had shoeboxes full of cash and a cache of weapons hidden in the walls. He was gainfully retired.

Today he is in solitary confinement under 24-hour surveillance at the Plymouth County House of Correction in Massachusetts. The food reportedly is not to his liking; he preferred the fare at Alcatraz, where he sojourned from 1959-1962. His trial is scheduled for June.

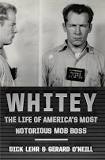

"Whitey: The Life of America's Most Notorious Mob Boss" by award-wining journalists Dick Lehr and Gerard O'Neill is their third book on crime and punishment (or lack thereof) in Boston. Lehr, a professor of journalism at Boston University, got his start in newspapering in Connecticut, at The Gazette in Old Lyme and later at The Courant before joining the Boston Globe in 1984. O'Neill is a Pulitzer Prize winner who was the longtime editor of the Globe's investigative team. The duo's previous book, the bestseller "Black Mass," was the basis for the recent movie starring Johnny Deep.

Lehr recently answered questions about their new book and Bulger.

Q. You have been covering Whitey Bulger for decades. What surprised you the most in researching this book?

Lehr: There were many surprises, really. One discovery that stands out was finding evidence of one of Whitey's major lifelong themes, his contention that he's really not such a bad guy after all. He's a Robin Hood or a good/bad guy, but not all bad. He's now writing letters from prison to his supporters pushing this notion. Of course, it's all nonsense, but we found he first struck this note at age 26 in a letter from federal prison, when he wrote: "I am no angel, but....." and then proceeded to claim he's not a hardened bank robber but someone who wants to do right.

Q. Before Whitey got away with murder with the help of the FBI, he had been arrested for committing a string of lesser crimes, starting as a juvenile delinquent, but suffered few if any consequences. Did our justice system help create this monster?

Lehr: I think so. In our book we were able to deconstruct the criminal record during his formative years in the 1940s and 1950s, and every time, for every arrest, which included an attempted rape charge, he managed to elude punishment. This certainly helped to create a sense of entitlement, that he was untouchable.

Q. For a bad guy, Whitey had some aid and comfort from quite respectable folks, didn't he?

Lehr: He did. He survived a long time, and studying him opens doors into many other aspects of the 20th century, one being politics, and the helping hand he received in the 1950s and 1960s, for example, from then congressman and speaker of the House John McCormick, one of the most powerful figures in the country. We uncovered letters from McCormick to prison officials and the Bulger family designed to improve Whitey's time in prison after he was busted for bank robbery in 1956.

Q. How has the scandal over the FBI's collusion with Bulger's crime spree changed how the G-Men treat informants today?

Lehr: The FBI and the Justice Department have revised informant guidelines to improve oversight and include federal prosecutors in the assessment of their informants. In theory, this should help, because previously the FBI was left to its own devices. But already there has been another mini-scandal brewing in Boston regarding a more recent informant for the FBI, so it's hard to gauge at this point.

Q. While in jail in Atlanta in the late 1950s, Whitey volunteered for a CIA-sponsored program that tested the effects of LSD on humans. He dropped acid some 50 times. Did you detect any subsequent side effects on Bulger?

Lehr: Whitey has claimed in letters that he suffered nightmares and sleeplessness as a result of LSD. Medical experts and scientific studies have not demonstrated any long-term damage from LSD use, particularly from pure LSD, which was used in the prison experiments, as opposed to the LSD sold on the street. The CIA had doctors test other drugs along with the LSD. We'll never know what those drugs were because the records have been destroyed by the government.

Q. Whitey was a voracious reader, which is intriguing. Do any titles stand out?

Lehr: He devoured World War II books, military history and history in general. He was a fan of Somerset Maugham and Evelyn Waugh and read other classics like "Dr. Zhivago." While hiding in Santa Monica, his interests included true crime and the handful of Bulger and Bulger-gang books published in the past decade.

Q. I understand Whitey is not giving interviews. But there is widespread speculation that he could drop a dime on the FBI and implicate others in the scandal that gave him immunity for decades in return for his ratting on rival mobsters. Can you speculate on that speculation?

Lehr: I'm not sure that Whitey could go up too high inside the FBI, because he dealt mainly with his Boston FBI handler, John Connolly, and Connolly's supervisor John Morris. He corrupted much of the organized crime squad in the Boston office, but many of the other agents' names have surfaced already in terms of gifts and money they took from him. But I do think Whitey could provide a lot more detail about the FBI corruption in Boston, a real blow-by-blow of times and places that likely would stun the public.

Q. Do you think he will spill the beans at his trial?

Lehr: Whitey is claiming through his attorney that he can't wait to tell his story, the core of which is his claim that the government gave him immunity from prosecution. In other words, a license to kill. If he testifies, it's going to be a circus, the climax of the proverbial trial of the century, and a big national story.

Q. Whitey helped hurt the Mafia, and then he and many of his associates went down. What is the current state of mobster-ing in Boston?

Lehr: The Mafia is doing its thing, and the Irish gangs are doing theirs. But it's scattered and decentralized. It's nothing like the so-called glory years of Boston's underworld, years dominated by outsized personalities like Bulger and the Mafia's Gennaro Angiulo.

Q. If Whitey granted you an interview with but one question that he would give a straight answer to, what would you ask him?

Lehr: There is one subject that remains intriguing: his brother Bill was a powerful state politician for decades who later was the president of UMass. Our book breaks new ground on the lifelong bond, on the loyalty between the two, including contact during Whitey's early time on the run beginning in 1995. Still, there is so much we don't know. My question would be: What about Bill? What was his involvement with you, if any, during all those years?

Q. Another book about Bulger by Boston Globe reporters Kevin Cullen and Shelley Murphy was published simultaneous to yours. Have you perused it?

Lehr: Not yet. Whitey and the FBI is a big topic that's warranted a slew of books going back to our own "Black Mass" [2000]. We think our new biography is the most comprehensive, in-depth take on Whitey's life and times.