Tales from the Kitchen

Those who use Rick Bragg’s latest meander into southern life as a cookbook will need to gird their culinary loins—and not be a scared of liberal doses of Crisco, fatback drippings, lard, bacon grease, cracklin’ meat, and such.

Never mind recipes for indigenous fare like “Squirrel Brains and Scrambled Eggs” or “Baked Possum and Sweet Potatoes.” The latter requires not simply the acquisition of a marsupial, but a live one to be fed “for a week or so” to “flush the nastiness from its system.” Talk about long prep time.

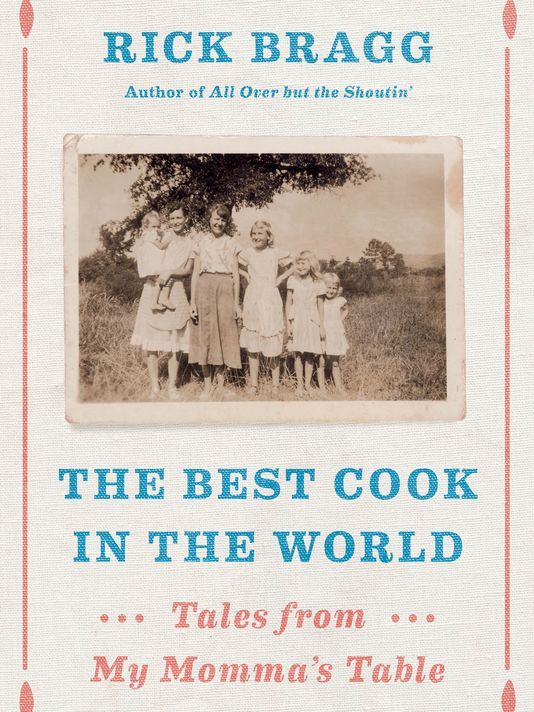

But this isn’t really a cookbook, or even a “food memoir” exactly, as the author suggests. "The Best Cook in the World: Tales from my Momma’s Table" is a collection of stories—wonderful, rollicking, poignant, sometimes hilarious tales about how generations of Bragg’s extended family survived from one meal to the next.

To families like his, in the hardscrabble foothills of the northeastern Alabama, food was a many splendored thing. It was love and reward, survival and joy, identity and adventure—an example of the last being the practice of “noodling,” or catching big river catfish barehanded.

Food from the skillets of cooks like the author’s mother, Margaret Bragg, was akin to an established religion: for her the greatest sin, according to her son, was “bland food carelessly prepared, devoid of salt, seasoning, and crisping fat.”

Bragg, a bestselling author and previously a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, is a storyteller of the first water. But translating his mother’s meals into recipes presented a challenge, even to a person who grew up on her cooking. She never opened a cookbook, not once, didn’t own one; her recipes were all in her head, passed down generations, some from before the Civil War. Plus, she didn’t measure out ingredients by cups and teaspoons, but rather by dabs and smidgens and handfuls. She had no use for a timer: she could tell when the cracklin’ cornbread, or what all, was done by smell.

Somehow her son got it all down on paper, sitting with his mother, watching her cook and listening to the stories of who taught her what when, and who taught it to the people who taught it to her.

In fact, the reader can skip the recipes altogether and concentrate on the stories wrapped lovingly around them—and still get a cooking lesson, how Margaret Bragg made plain food well seasoned taste like a preview of kingdom come.

Take the story of Clem Ritter. Margaret’s father, Charles, was racing home with her and her siblings one evening, hoping against hope not to be too awful late for a dinner his wife had been laboring over most of the day.

Well, wham, he ran straight over Clem Ritter as she was crossing the road, his tire going directly over her head, which Margaret described as being “all whomp-sided.” There wasn’t much they could do for her. So they laid her down by the side of the road, and made a beeline for dinner. Such was the allure of southern home cooking.

The story startles the author, hearing it for the first time from his 80-year-old mother, as it does the reader. They just laid her by the side of the road? And Clem Ritter, it is revealed at the tail end of the telling, was part of the family. She was Margaret’s dog, named after the victim in a true crime magazine story—named a full three years after she was whelped. How they got her to come before that is not clear.

And, happy to report, Clem Ritter was up and around after dinner, although she was whomp-sided for a spell.