The Shah's Legacy

It almost seems as if Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, aka the Shah of Iran, wasn’t ruling a great nation so much as auditioning for a blockbuster miniseries. He had it all: a beautiful queen, mistresses galore, absolute power, corrupt kin, and a hedonistic daughter turned Islamic fanatic.

The archvillain in this drama, Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, made Lex Luthor look like a milquetoast.

In reality, the Shah, who fled Iran in 1979 and died the following year, was a serious ruler whose successes and failures have had a profound effect on the world right up to the present. He was instrumental in turning oil into a geopolitical weapon and bringing the bugaboo of nuclear power to Iran. Had he staved off Khomeini, the Middle East might be far less tumultuous today.

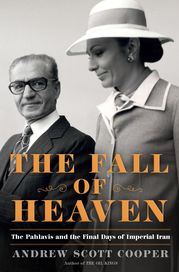

In "The Fall of Heaven" (Henry Holt, 499 pp., ***½ out of four stars), Andrew Scott Cooper brings the Shah, along with his colorful retinue and turbulent times, back to life. It is revisionist history in parts — and mostly sympathetic to the king and his queen Farah. She was among the many people the author interviewed for this thoroughly researched and richly detailed account.

The Shah, according to Cooper, was nothing like the blood-soaked tyrant portrayed by the Western media in the 1970s. Rather he was a predominantly beneficent autocrat whose White Revolution raised his people’s incomes and expanded literacy and women’s rights.

There clearly were abuses, including the torture and death of political opponents, but they were substantially less than were claimed by regime opponents and reported by many journalists. The author cites investigations by the Red Cross and the Islamic Republic of Iran itself to support his thesis. He also points out that the ruthless Khomeini made the Shah look like a piker when it came to human rights violations.

In fact, the Shah was something of an old softy according to many observers: reluctant to unleash his security forces on violent protesters not just before his fall, but also during previous uprisings in 1953 and 1963. He repeatedly offered concessions to Khomeini and his rampaging mobs.

In late 1978, King Hussein of Jordan flew to Iran to buck up his fellow royal, even volunteering to lead the fight against Khomeini’s followers. The Shah politely declined the offer. He would not slaughter his people to save his throne.

Earlier, in August, an even more astounding offer came from none other than Saddam Hussein, a true tyrant if there ever was one. He told the Shah to just give him the word and he would kill Khomeini, then in exile in Iraq. The Shah said no thanks.

Two years hence, Saddam’s Iraq and Khomeini’s Iran would fight a brutal eight-year war that killed an estimated 1 million people on both sides.

America was largely clueless about Iran. The CIA had not listened to the tapes of Khomeini’s virulent sermons that were on sale in Tehran. “The Americans were sure that Khomeini was a moderating influence over the leftists and radicals in his entourage,” Cooper writes.

Compounding this intelligence failure was President Jimmy Carter’s preoccupation with brokering peace between Israel and Egypt and the Shah’s reluctance to use the overwhelming power of his security forces to stay in power.