The Tupperware Lady

In the 1950s Brownie Wise accomplished for sales what Elvis Presley did for music. She shook it all up.

Just like online today, consumers back then could buy what she was selling — Tupperware — from the comfort of their homes, but not from a pushy, foot-in-the-door huckster. First the hosting housewife and the salesperson partied with a sociable group of friends. They played some parlor games, like toss the Tupperware bowl full of grape juice across the living room to see if the patented seal held. Afterwards the women purchased plastic home products like there was no tomorrow.

A divorced single mother with the perky good looks of Doris Day and the positive outlook of Norman Vincent Peale, Wise rocketed into the national consciousness as the head of Tupperware’s Home Party Division from 1951 to 1958.

She was a charming Southern belle who instantly became the face of the company, the wizard who moved ever more bowls, cups and containers that were manufactured by the company founder, Earl Tupper, a cold and crusty Yankee inventor.

Wise and her party minions, more than 10,000 strong, often outpaced the capacity of Tupper’s factories — for example, in 1953 when sales doubled from the previous year. Ensconced in her fiefdom near Orlando, Wise wasn’t shy about telling her boss up north to pick up the pace.

She also understood the value of positive publicity, even as her growing celebrity made Tupper jealous. The Tupperware craze was featured in national magazines such as Life, and Wise graced the cover of Businessweek, the first woman to do so.

Long before Oprah and Ellen were handing out cars like M&Ms, Wise rained down Cadillacs and Fords (not to mention mink stoles) on her top performing sales people. Tupperware not only afforded many housewives the opportunity to work outside the home, it also showered them with recognition for their good works.

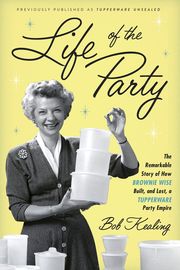

"Life of the Party "by Bob Kealing is a workmanlike account of the rise and fall and eventual resurrection of Brownie Wise, who was simultaneously a woman of her time and well ahead of it. While she stood up to Tupper and other male colleagues, she surrounded herself with a cast of all-male junior executives.

Kealing is an Orlando TV reporter who is sympathetic to his subject — to a fault. He leaves the reader hungry at various points for additional information about Wise’s private life and her relationship with her closest colleague who stayed on to run sales after Tupper unceremoniously fired her.

Most notably, the author introduces two-time presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson, of all people, as “someone special in her life” and essentially leaves it at that. They wrote affectionate letters to one another and she called him Andy — end of love story.

The author glosses over this bombshell as if he was loath to pry. A movie based on his book starring Sandra Bullock is in the works; Hollywood undoubtedly will make much more of the Andy Stevenson angle.