Cold War Musician

He was every bit as famous as Presley and Sinatra, neither of whom had a tickertape parade down New York City’s Canyon of Heroes. Before he died in 2013, he had performed for every US president from Harry Truman to Barack Obama. His soulful soaring sound brought tears to people’s eyes, among them Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who would hug him, kiss him on both cheeks, and hang out with him at his Moscow dacha.

In 1958, at 23, this supernova of classical music — from Texas, of all places — graced the cover of Time magazine. He had taken both the Soviet Union and the United States by storm while winning a prestigious international music competition in Moscow. By the end of his last performance there, the judges, many of them Russians, abandoned all objectivity: They stood and cheered right along with the audience. He didn’t just win; he buried the competition. He also stole the heart of a saber-rattling nation that threatened his country with weapons of mass destruction.

He was tall and handsome, with big wavy hair, and was mobbed by fans at home and abroad. The one sure thing Americans and the Russians could agree on during the Cold War was that this man, né Harvey Lavan (Van) Cliburn, played the piano like nobody else.

In 1960, after the Soviets shot down an American spy plane and a petulant Khrushchev torpedoed his summit meeting with President Dwight Eisenhower, things got chilly, indeed. All planned superpower contacts were cancelled except one. The Soviet leader insisted that Van Cliburn still come to Moscow to perform his Russian repertoire: Tchaikovsky, Rackmaninoff, Scriabin, etc. So he did.

For years thereafter, when American and Soviet leaders met, Van Cliburn was often there, too, applying his music like a salve to the inevitable abrasions of geopoliticing. He was with Nixon and Brezhnev in 1972, with Reagan and Gorbachev in 1987, with Bush and Putin in 2001.

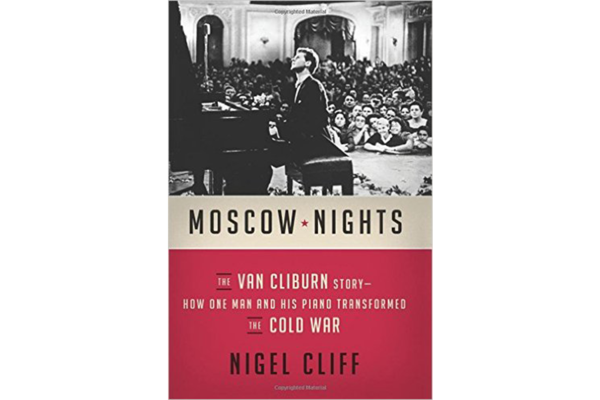

Nigel Cliff’s fourth book is an engaging, richly detailed account of a remarkable man. That Van Cliburn has faded so from our collective memory is almost as astonishing as this improbable tale itself.

Moscow Nights, The Van Cliburn Story: How One Man and His Piano Transformed The Cold War is not a biography per se — there are two that the author draws on — but rather a narrative organized on the intersection of his charismatic music and superpower rivalry, from the 1950s right into this new century. There are whole chapters devoted to Cold War machinations: for example, Sputnik and the space race, Khrushchev’s two visits to America, and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

In 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan were trying to agree on wholesale reductions of their nations’ nuclear arsenals, but the negotiations had become contentious. That evening, at a White House dinner, with feelings still raw, Van Cliburn took center stage.

He deviated from the approved program, first playing the Soviet national anthem to the astonished star-studded audience, then the Star Spangled Banner. Next he spoke extemporaneously about his love for music, for his country, and for the Russian people. Way past his allotted time, he agreed to play an encore at the request of Raisa Gorbachev. His rendition of “Moscow Nights” turned the formal affair “into a full-throated sing-along,” Cliff writes.

The author asserts that this remarkable moment contributed to an improved atmosphere in the subsequent negotiations: Four years hence Gorbachev and George H.W. Bush would agree to eliminate 80 percent of the world’s strategic nuclear weapons. It’s seems like a bit of a causal stretch, but who knows. Let it go.

The book is not all politics, of course. Cliff deftly places his subject in the context of the evolving musical culture of the past two centuries. Before Van Cliburn fell hard for Russia and its people, he already had embraced their music.

At the age of three he could play complex pieces by ear, and his mother, a distinguished pianist herself who had met the great Sergei Rackmaninoff, facilitated matters from there. At the Julliard School he had to audition to earn the chance of studying with the legendary, and Russian-born Rosina Lhévinne. “His playing thrilled a deep Russian chord in her,” Cliff writes. “She found space in her class.”

Soon he would be thrilling packed auditoria, including Carnegie Hall, and even larger audiences. In 1955, Steve Allen invited the 21-year-old to perform on the Tonight Show. Elvis, who was the same age, wouldn’t debut on national TV until the following year.

But it would take Russian audiences to propel Van Cliburn into an even higher orbit. He transported them back to a time before commissars and programmed socialist realism: “His playing was ecstatically lyrical, thrillingly Romantic, and symphonic in scale—tears glistened in many eyes,” Cliff writes.

That he was better at playing their music, Tchaikovsky in particular, than their own virtuosos was a revelation. That Russian officialdom would play fair and let him win their own competition was an eye-opener for many Americans. It was hard not to smile seeing the rotund, five-foot-three-inch Khrushchev straining up to hug and kiss the lanky, six-foot four-inch American. Perhaps the world wasn’t doomed to unrelenting hardball politics after all.

The FBI, of course, took note of the young man’s affection for America’s rival, opened a file on him, and listened in on his phone calls. They learned that he was gay, but that was all, other than that he was a good Christian and loved his country.

Not everyone on the other side of the Iron Curtain was happy with this young American phenom. One wizened Russian pianist wondered why Van Cliburn swayed back and forth so much and looked skyward when he played. A fellow countryman explained it to him: “He looks up because he is speaking to God.”