War of the Worlds

Fake news is old hat today. Witness: John Stewart and Stephen Colbert, The Onion, and recent examples of TV newscasters getting frisky with the facts. Ultimately, what’s news may be in the eye (or ear) of the beholder. But the Gold Standard of bogus broadcasting remains Orson Welles’s 1938 “War of the Worlds” on CBS Radio, which convinced many listeners that the Martians had landed – in, of all places, New Jersey.

And it wasn’t even news per se: It was a regularly scheduled dramatic performance of "The Mercury Theatre on the Air" that incorporated simulated reporting to advance the plot line. The Martians descended on the sleepy town of Grover’s Mills on Halloween eve, and quickly crushed New Jersey and America’s hastily assembled armed forces (talk about rapid deployment) in about 40 minutes of air time (and now a word from our sponsor).

If the subsequent real news reports on the fallout from Welles’s fakery are to be believed, myriad Americans panicked: purportedly stampeding in the streets, clogging highways, and loading their trusty guns (if they weren’t already loaded). Welles, that 23-year-old phenom of stage and later screen, apparently had made a fool of an entire nation. He had freaked out what would later become known as the “Greatest Generation.” Or so the storyline went. At the time, this narrative was far scarier to many Americans than the original broadcast. Was America a nation of sheep ready to believe any nonsense that came over the airwaves?

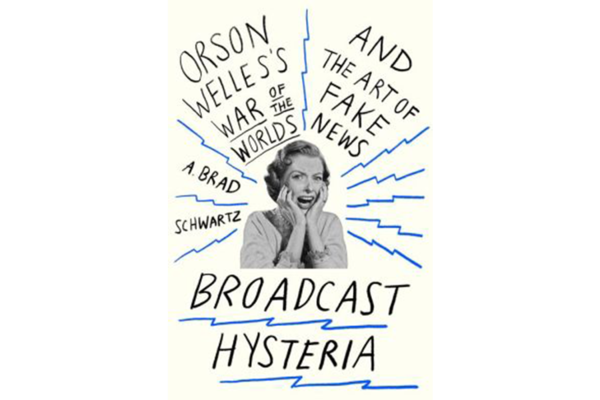

But what Americans have come to accept as settled history about this infamous event ain’t necessarily so, according to A. Brad Schwartz in Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News. A 2012 grad of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, the young author is something of a phenom himself. His well researched first book, which grew out of his honors thesis, challenges conventional wisdom. He also deftly places Welles’s caper in the perspective of the time, when a real world war was looming, and the new medium of radio was enjoying a fleeting “Golden Age” as it simultaneously was experimenting with other dubious forms of journalism.

Schwartz begins his account with the saga of a New York City couple, John and Estelle Paultz, who believed. They fretted about family in New Jersey and ran to the rooftop to look for evidence of the invasion, whether explosions or clouds of poison gas that were reported to be heading north from Jersey. They fled their apartment and headed for the subway, telling anyone they saw about the invasion. They were surprised by the normalcy they encountered. The world was ending and no one seemed to have noticed but them. Before they realized they had been fooled, they were stranded in Connecticut, on a train, with 56 cents to their name. Some kindly Yale students chipped in to pay for their round trip.

John and Estelle were not alone. Many were concerned, even terrified, but most were not. The author reports that no Americans died or were substantially harmed in the perpetrating of this hoax: “Even for fully frightened listeners, panic was the exception, not the rule.” After all, the show was far from the highest rated offering that evening, reaching perhaps four million radio sets.

Among other sources, the author mines nearly 2,000 surviving letters from people responding to the broadcast, including some 1,400 sent directly to Welles and "The Mercury Theater" that only become part of the public record in the past decade. A surprising number of people, among them many who had been duped, praised Welles for his theatrical tour de force. Others were more worried that the show would inspire the government to increase censorship of radio programming.

How listeners reacted to the broadcast depended, Schwartz shows, on the context of how they heard, or misheard the “news” or if they learned of the “invasion” from others. It was a time, after all, when a real world war and invasions were distinct possibilities. Referencing a study of public reaction at the time, the author writes that roughly “a third of the listeners thought it was an attack from an earthly enemy, a third thought it was some other kind of disaster, and a third believed in supernatural invaders.” Clearly the consumption of news, like journalism itself, is not an exact science.

And while there were examples of individuals being terrified and panicking, there was no mass hysteria. What was hysterical was how real reporters from allegedly bona fide news organizations blew the impact of the broadcast out of proportion, Schwartz insists. Like Welles, these scribes apparently subscribed to the maxim attributed to Mark Twain: “Never let the truth stand in the way of a good story.”

Welles’s great hoax has become part of American folklore, copied periodically here and abroad. One such broadcast resulted in fatalities. Fake news became part of the culture. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor three years after “War of the Worlds,” radio journalists were careful to note that what they were reporting was the real deal.