Watergate Revisited

Like a bad penny, the Watergate scandal keeps returning.

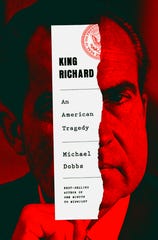

The last of the secretly recorded White House tapes that sealed President Richard Nixon’s fate would not be released until 2013. During the past half century the suffix “gate” routinely has been appended to every noteworthy instance of political malfeasance. But you never forget your first scandal, even if its twists and turns have grown hazy in the fog of history. Thankfully, journalist and academic Michael Dobbs rides to the rescue, bringing Watergate back into focus in his latest book, “King Richard: Nixon and Watergate: An American Tragedy” (Knopf, 416 pp., ★★★★ out of four).

Nearly 50 years ago, on June 17, 1972, burglars were arrested breaking into the Democratic National Committee Headquarters, which was housed in the Watergate hotel in Washington, D.C. The gang who couldn’t burgle straight was there to get dirt on the opposition at the behest of Nixon’s reelection committee, known aptly by the acronym CREEP.

Nixon, of course, needs no introduction, but Dobbs reacquaints the reader with a supporting multitude of misbehaving miscreants, a cast of characters worthy of a Graham Greene novel – connivers, fabulists, rats and back-stabbers.

Remember mouthy Martha Mitchell? How about the closed-mouthed E. Gordon Liddy? Say “hey” again to L. Patrick Gray, who as the acting director of the FBI destroyed documents from E. Howard Hunt, one of the Watergate burglars. Gray was the boss of Mark Felt, aka Deep Throat, a bureau veteran who thought he should have gotten the top job.

This fast-paced opus would be a rollicking fun read, a beach book even, if it weren’t so doggone real – and if it wasn’t so reminiscent of recent machinations in our nation’s capital. But fun or not, this is an important book at this moment in our tortured political history.

Nixon also believed reporters were the enemy. He made a list and checked it often. Democrats were his enemies, as were labor leaders, think tankers and of course protesters. His list included Paul Newman and Joe Namath.

Nixon was consumed with hate and he imagined others were as permeated with venom as he was. Of the protesters at his triumphal second inauguration, he said, “They’re really so frustrated. They hate the country. They hate themselves. And that’s what it’s really about. It isn’t just the war. It’s everything.”

A likely reason many of the protesters were there was that in 1968, then-candidate Nixon had proclaimed that he had a “secret plan” to end the Vietnam War. Four years into his presidency the war continued apace and more than 20,000 American soldiers and countless Vietnamese had perished during his first term.

The book begins with Nixon on top of the world. He has thrashed the hapless Democrat George McGovern in a landslide of truly epic proportions, winning 49 states. His approval rating at his second inauguration was a staggering 68%. But while his friends, family and supporters celebrated on election night, Nixon would later admit that he couldn’t explain “the melancholy that settled over me on that victorious night.”

Soon enough, melancholy would be the appropriate emotion. The first 100 days of Nixon’s second term increasingly would be consumed by the metastasizing scandal. Dobbs masterfully captures the great unraveling in his vivid and illuminating narrative. By May 1973, just months into his second term, Nixon was already contemplating resigning. The amount of time he and his staff were spending on Watergate, rather than running the country, was stunning.

Watergate, Nixon knew, was just the tip of the slippery iceberg. Nine month earlier, the White House “Plumbers” also had broken into the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, looking for dirt on the man who had released the Pentagon Papers to the media. They found none.

While there is incontrovertible evidence that Nixon actively covered up Watergate, there never has been conclusive proof he ordered the break-in. But his relentless thirst for ammunition to use against political enemies surely motivated his ethically challenged underlings. Bob Haldeman, Nixon's chief of staff who served 18 months in jail for his role in Watergate, thought this to be the case.

Dobbs recounts a revealing incident of a Nixonian target that ultimately wasn’t burgled – the Brookings Institution, which the president believed harbored material he could use against his predecessor, Lyndon Johnson. Nixon told his aides, “I want it implemented on a thievery basis. Goddamn it, get in and get those files. Blow the safe and get it.”

Curiously, Dobbs closes the book in July 1973, more than a year before Nixon resigned. The author doesn't address the drama and national trauma that transpired in between. Many readers, even those who lived through Watergate and watched the Senate hearings on television, will be left wondering how in the name of Sam Ervin, Nixon held on for that long. Perhaps a sequel is in the works?