Women and Islam

By Jackson Holahan

The Carter Family of country music fame, in their 1928 hit, reminds us all to “Keep on the Sunny Side of Life.” This is welcome advice for those who run into life’s pettier misfortunes: stepping in a puddle, depositing lunch on one’s trousers or, say, believing in Tiger Woods’s steadfast family values. Bouncy lyrics aside, sometimes keeping on the sunny side prevents one from grasping the depravity and anomie of certain situations. The status of women in the Middle East is one of these instances.

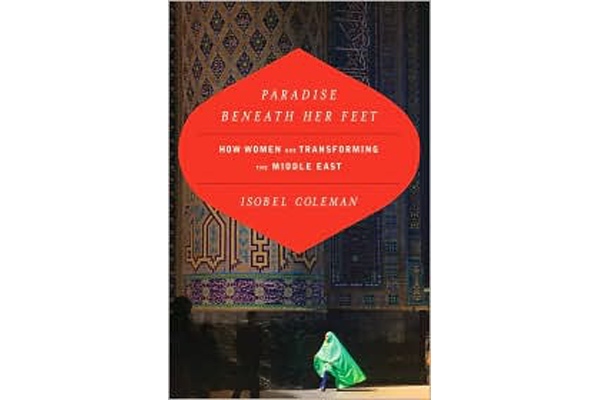

In her latest book, "Paradise Beneath Her Feet: How Women Are Transforming the Middle East," Dr. Isobel Coleman, a senior fellow on the Council of Foreign Relations, would have us believe that women across the Middle East are successfully empowering one another to end what is often a brutal repression of their gender.

Coleman’s work deserves praise for its noble aims. During her extensive travels from Morocco to Afghanistan, Coleman details numerous encounters with various women who are working on the local, provincial, and national levels to improve the lot of their sex’s standing. Take Salama al-Khafaji from Iraq, a dentist who is the only person on the Iraq Governing Council elected by her peers and not appointed by US officials. Khafaji has used her position to push for female education and scholarship, much to the disdain of the Shiite orthodoxy. She has paid a heavy price for her trailblazing zeal. Insurgents murdered her son in broad daylight and her husband divorced her after she refused to temper her reformist views.

Coleman’s work is filled with three-to-five page snapshots of courageous stories like Khafaji’s, which in a way are as encouraging as they are disheartening. Every gain women make in many of these profiles seems to be achieved in the wake of some great personal loss.

Unfortunately, aside from being connected by diverse conceptions of female empowerment, Coleman’s vignettes seem pieced together until acceptable book-length pagination was achieved. Rather than delve deeply into a handful of women’s accomplishments, Coleman adopts the more-is-better approach and seems to give a superficial account of every woman in the Middle East who has conducted anything resembling a feminist mission.

In a book that so directly addresses the cultural and religious reverberations of Islam, “Paradise Beneath Her Feet” is curiously devoid of any direct engagement with the Koran’s treatment of women. Coleman repeatedly reminds us that the Koran does not allow for the mistreatment or subjugation of women, but not once leads us to the passages in question that, apparently, have been so misconstrued.

The tale of the underdog is an American favorite. The 1980 US Olympic Hockey team made us believe in miracles, as Al Michaels so exuberantly proclaimed. Coleman’s book reads like an underdog tale, constantly tapping on the heartstrings of readers’ desire to see these women treated as the intelligent, independent, and competent human beings they are. Unfortunately, even the rosiest take on the lasting effects of these women’s actions falls well short of anything resembling an underdog triumph.

After spending 250 pages lauding the work of women improving their gender’s political and economic standing, Coleman remarks, “For all their good intentions, these women will never be able to overturn 1,400 years of oppressive Islamic law.” In a book so filled with genuine passion and commitment to female empowerment, the above quote seems woefully inadequate to describe the extent to which such oppressive laws are, in many countries, discounting the value and contribution of 50 percent of a population.

A very thick undercurrent of resentment and disgust toward Islam typifies this book’s tone. There is plenty to be angry about, especially from the perspective of an American reader. Something is wrong when women are not accorded even the most basic rights of marriage, divorce, inheritance, and education as are their male counterparts. What is equally frustrating is the unwillingness of foreign intellectuals, Coleman among them, to call these attitudes what they truly are: disgraceful anachronisms that have done nothing to position the societies that nurture them as competitive and useful in the modern world.

Coleman’s argument should strike a discordant note in the minds of many of its readers. It will never be possible for any group to create a meaningful society while ignoring and persecuting one-half of its human capital.