Women at the Front

American women have been fighting and dying for their country since the Revolutionary War. But, in a classic Catch-22, women – because they weren’t officially supposed to be on the front lines – did not reap the same career opportunities as their male counterparts for being in harm’s way.

Finally, in 2015, all combat roles were open to women; by then nearly 150 had died and more than 850 had been wounded in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Besides shooting to kill, women made unique contributions to America’s two Middle Eastern wars. Because of cultural sensitivities, half the populations of Iraq and Afghanistan were off-limits to male soldiers. Knowing this, insurgents often used women’s bodies to hide sensitive materials, such as documents, rolls of film and cellphone SIM cards.

Enter FETs, or female engagement teams, whose members could effectively frisk women at checkpoints and on combat missions, while also extracting valuable intelligence.

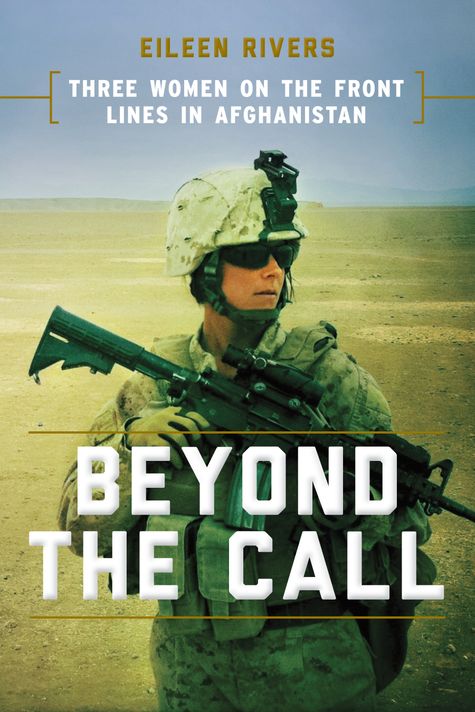

“Beyond the Call: Three Women on the Front Lines in Afghanistan” (Da Capo Press, 288 pp., ★★★ out of four) by Eileen Rivers, digital content editor for USA TODAY's editorial page and herself an Army veteran, makes an important contribution to understanding the evolving role of women in service to their country. She ably documents how females in arms, who represent 16 percent of America’s military, make their nation stronger.

Members of Female Engagement Team (FET), US Marines GySgt Michelle Hill (L) and Cpl. Reagan Odhner (C) from the 1st battalion 7th Marines Regiment unload their M4 rifles after a patrol with Afghanistan National Army (ANA) soldiers in Sangin in Helmand Province on June 6, 2012.

Members of Female Engagement Team (FET), US Marines GySgt Michelle Hill (L) and Cpl. Reagan Odhner (C) from the 1st battalion 7th Marines Regiment unload their M4 rifles after a patrol with Afghanistan National Army (ANA) soldiers in Sangin in Helmand Province on June 6, 2012. (Photo: ADEK BERRY, AFP/Getty Images)

The book is not without flaws, including occasional unsubstantiated assertions. Rivers writes about a woman who disguised herself as a man and fought in the Revolutionary War: Deborah Sampson could read, which the author inaccurately terms as “a rarity in eighteenth century America.”

Here are five things to know about American women in the military:

- Ability to gather intelligence.

They were uniquely able to gain valuable intelligence from their interaction with Muslim women by, as Rivers writes, “talking to the people who had observed the enemy most – the women who lived among them, were victims of their violence, and had spent years watching insurgents’ day-to-day activities.”

- Helping empower local women.

The work of FETs went beyond security- and intelligence-gathering to encompass nation-building objectives: strengthening local communities by empowering women to work, register to vote and serve as police officers.

Author Eileen Rivers.

Author Eileen Rivers. (Photo: Mick Cochran, USA TODAY)

- Restrictions on female soldiers.

Female American soldiers and many Afghan women had this in common: The former could not leave their base, on foot or in a vehicle, without being accompanied by a male soldier; the latter often were confined to their homes unless accompanied by a male relative.

- Engaging with Muslim women.

Begun by the Army in 2004 and adopted by the Marines in 2006, the use of female soldiers to engage with Muslim women had grown by 2011 to consist of 149 FET teams from 14 countries in Afghanistan alone.

- Increasing roles for women in the military.

The progress of women in the military has been slow but relentless: In 1901, female nurses became part of the U.S. Army; more than 100,000 women served in World War II; in 1980, the first female West Pointers graduated; in 1989, a woman led a combat unit in action for the first time; in 1993, women were cleared to fly helicopters during combat missions; in 2015 two women graduated from the arduous Ranger School at Fort Benning, Georgia.