Victor, Sojourning Soviet Journalist

Victor Gribachev, a Soviet journalist, was trying gamely to make sense out of the chaos below his perch in the gallery of the Connecticut House of Representatives. Rep. Mary Mushinsky was arguing for an amendment that would require Connecticut cars to get better gas milage. "I have never seen one of our Soviet deputies pregnant," Victor exclaimed about the woman who was debating for two, as it were.

Next he noted that the legislator sitting next to Mushinsky was reading the newspaper — no, his head started to bob and he nodded off!

Turning to a fellow journalist, Victor pleaded, "David, can you tell me what is going on here?"

Somehow the words "democracy in action" seemed inappropriate, if not downright satiric. Were I quicker-witted I might have suggested that we have an inalienable "right to doze" in the Constitution State. What confused Victor was not simply this one lackadaisical lawmaker. The entire floor of the House was a beehive of private conversations, laughing leaders, and scurrying staffers. I tried to explain that in Connecticut there is also something known as the "party line" and that the fate of this amendment was probably a foregone conclusion (indeed, it was easily defeated).

Victor looked at me as if I belonged with the inmates down below. Shaking his head gravely, his natural Mohawk strip atop his balding pate moving like the arrow of an unsettled compass, he suggested we take five for a smoke.

Soon, however, the most astonishing moment of the day — and perhaps of his entire three-month sojourn in Connecticut, occurred. Rep. David Anderson would introduce this bright, shy 40-year-old man to the full House. The same people who didn't have the time of day for one of their own members rose in unison, clapping, whistling, and stomping their feet for Victor Gribachev, member of the Community Party and temporary pundit for The Day newspaper of New London.

This wayfaring homebody, a devoted family man and polite to a fault, was a long way from Moscow and the confusion to which he is accustomed. Victor works for The Journalist Magazine (similar to the Columbia Journalism Review) and was participating in an exchange program of American and Soviet scribes.

Despite being perceptive about other aspects of our culture, Victor never got the hang of our legislature (he didn't even write about it). He found it as elusive as our national pastime, which he observed at Fenway Park along with Day publisher Reid MacCluggage. Before this mandatory field trip (Victor described it as "non negotiable"), he asked, "What does the man holding the club do?" I tried to explain, but he shook his head and reached for another of his potent Soviet smokes.

Victor's stay here was not easy for him. He missed his family dearly and worried how his wife was coping with their 8-month-old son (they also have a daughter, 11, and a son, 20). He does not make fiends easily and fended off waves of invitations from his new colleagues for dinner, the theater, cookouts etc., in part, because there were so many community and official engagements he simply could not refuse. At times he was tempted to preface his conversations with curious and impolitic Americans with "Yes, I own a dishwasher and a color TV also." Throughout his visit, Victor was busy making notes and collecting data for a book he hopes to write about American journalism.

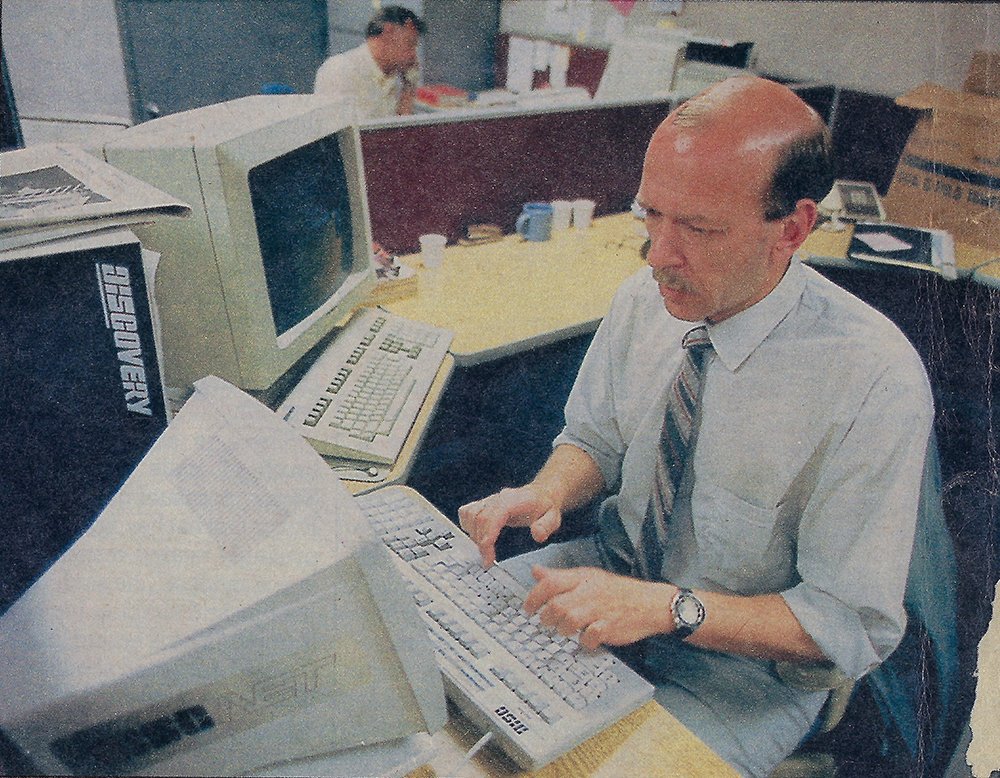

Then there was the challenge of writing coherently in English about a strange place with its peculiar inhabitants, and on a computer, no less. The only censorship he had to deal with was his own politeness and the lack of space in the paper. He wrote many more columns than The Day could absorb and was far too respectful a guest to include observations like this under his byline: "I go to cafeteria and I see some really fat women consuming big amounts of food and speaking of diet. First you eat, then you go to Weight Watchers. Everyone is health-oriented here and that is good, but it shouldn't be the main thing."

Victor mastered word processing in a day, rather than the two weeks he had anticipated, and surprised himself by his other accomplishments. His columns appeared twice a week and were often quite compelling. To his delight, his American editors gave him free rein, even maintaining a policy of non-intervention with much of his Russified prose: sentences like "I am not the celebrity and surely never will be the one" added an appealing exotic flavor to his observations. Like many visitors before him, he was both attracted and repelled by this restless "land of opportunity."

"I hate to shop," Victor said several times as we meandered through the interminable neon promenade of Waterford's Crystal Mall, that gaudy pantheon to capitalism. Yet shop he must, because relatives and friends back home had put in their orders. He brought with him paper cutouts of their various shoe sizes. He could buy a VCR, but wasn't sure if he would. Money was not the issue: his salary here was $280 a week plus lodging. He simply was't sold on the notion of spending more time in front of the tube (although he did develop a taste here for CNN and reruns of MA*SH*. All he wanted for himself were some camouflage T-Shirts to wear fishing back home. But mall prices were too high, he decided.

So we went down a flight of stairs to fast-food alley and ordered coffee. "All you want is coffee? the girl behind the counter asked, her eyes darting between us. It was mid-afternoon and the taco stand was empty. Her supervisor came by to look us over upon hearing Victor's accented reply, "Yes, thank you, just coffee, please." Reassured by her boss that it was all right to dispense coffee only, she asked, "Large or small? Cream and sugar? For here or to go?"

Victor contained his growing agitation until we were seated. "What is the big idea of putting on these lids," he grumbled. He had come from a land of too little to one where there was way too much. In the spirit of glasnost, he freely conceded the point in his very first column in America: "What troubles them [Soviet citizens] may be summed up in a short phrase: We don't know where we can get nutrious food for our children ... the inability to take care of children drives you mad."

Our superstores stocked to the rafters with myriad wonders would revolutionize life in Moscow. Money is not the problem for the likes of Victor. He is comfortably middle class by our standards, owning a $12,000 Fiat and having use of his father's dacha near Moscow. And yet every morning before work he gets in his car and drives to the "milk kitchen" to get his daily prescription of dairy products for his baby. The women at his office slip out during the workday to shop because if they wait until 5 p.m. "there will be nothing," he explained with disgust.

The pendulum has swung the other way. Russians now compulsively speak of the ills of their nation the way they once touted only its "historic achievements." Victor wrote about drug addiction in his country, Russian motorcycle gangs (sporting obscenities scrawled in English on their jackets), even an incipient Soviet mafia that he said is growing bigger and bolder right along with other private enterprises in the former Communist "paradise." Chronicling our society's defects, as Soviet journalists did exclusively for so long, is now considered passé back home. "Our readers want to hear that everything is good in America; it is because of our guilt from the Cold War," he said.

"I would take hundreds of Crystal Malls home with me," he said wistfully as we sipped our coffee, thinking no doubt of his wife, who does most of the hunting and gathering for the family. When he visited the United States in 1974 as an interpreter for a group of touring Soviets during the first wave of detente, he was astonished to fine watermelons, among other wonders, for sale in the dead of winter. No lines, just grab as many as you could carry.

So he put one in his shopping cart. To his greater surprise, the checkout clerk insisted he let her replace it with one that didn't have a slight blemish. Was this some sort of trick? he wondered. So Victor clung to his flawed watermelon like it were a life raft. Enough already! Let me go in peace with my imperfect fruit. It was all he could do to contain his excitement about this brave new consumer paradise, he recalled with a smile.

But for all its apparent splendor, the Crystal mall is not pushing watermelons. More typical of its stock in trade are talking scales ("You weigh 194 pounds; have a nice day"). "Does the mall have an inn?" Victor asked. He was disappointed that it didn't. He pointed out that there was a bank, and places to eat and rest inside the mall, that the exit signs are far harder to locate than the entrances. "With the inn, there would be no need for exit signs," he concluded with a grin. He termed the purpose of the mall to be, "Robbery with a smile."

After listening to George H.W. Bush tell graduating Coast Guard Academy cadets in New London [in 1989] that "Communism is dead," Victor was prodded by publisher MacCluggage into rebutting the speech in his column (Victor had risen and applauded Bush's remarks with the rest of the visitor's gallery). He wrote just enough about the shortcomings of our society to ask: "Is capitalism dead?" He went on to describe in greater detail his own country's problems and efforts being made to solve them. He cautioned, however, "The biggest mistake would be to consider this process a conversion to a capitalist society."

Yet in private, he confessed that many Soviets, including himself, are not sure themselves what to call the recent tumult in their nation. "Right now an engineer who is working eight hours a day is earning one-fifth as much as some guy making stone-washed jeans," he said, asking, "So where is the progress for the working person? Our leaders cannot explain this gap and how we should be dealing with it."

Sitting on a bench at State Pier in New London, with Electric Boat Shipyard across the Thames River, Victor spoke of his children's future: "They are nice kids, and I am not worried in terms of paying for college education — that depends on knowledge only. I am not worried about them getting jobs; they will have lots of opportunities. What I am worried about is their beliefs. I brought them up so they are proud to live in the Soviet Union, a socialist country, and they understand that there are a lot of benefits. But right now they see there are a lot of hardships. I hope they will not be so frustrated about it that it will ruin their beliefs in socialism."

His oldest son is planning to apply to join the Communist Party, as Victor did nine years ago. About one in every ten Soviet citizens is a member. Victor is atypical in other ways, too. He cooks for his family and helps around the house, habits that he said make him "not like so many Russian guys." He works very hard, appearing at The Day newspaper almost every day, Sundays and holidays included. When he left for Moscow, there were more than a dozen unpublished columns in his computer file. Also, he does not drink.

In many ways, Victor resembles a solidly conservative American, wary of a society in great flux. He strongly favors the death penalty. He opposes flag burning, and pointed out in a column that if it was wrong to burn Old Glory it should be wrong to burn any flag, even that of Iran, a nation for which he shares America's general distain. He is skeptical of Mikhail Gorbachev, whose foreign policy he likes but whose economic moves he faults, and he is wary of other Soviet politicians as well. "It is easier to criticize everything than it is to offer a constructive program; I am very worried about this," he said, referring to the turmoil of budding (and televised) democracy at home. He is concerned, too, that when the newly invigorated Soviet press is through exposing skeletons in closets, there will be no heroes of socialism left.

A casual question about Raisa Gorbachev ignited a surprisingly heated response: "She is not modest," he said, pursing his lips and shaking his head his head in disgust and adding "She is acting like she is number one. We are mad about her" [i.e. mad at her]. He and Nancy Reagan agree on this point.

For all his shyness, sometimes gloomy Russian fatalism, and homesickness, Victor enjoyed himself at times. He found his coworkers and Americans in general very friendly, at time too friendly. "I am not here to give bear hugs and be bear-hugged by all the Americans," he said. "I am a working journalist!"

One of the stories he worked and delighted in was about the World Whores Congress that was held in San Francisco this summer. His efforts to interview various officials of this bourgeoise Internationale became a running gag. "Oh, yes, sure, David, we have whores in Soviet Union, but so far they haven't had the time to set up a congress," he told me with a big grin.

Victor grew to like journalism American style. "I feel so free writing here," he said. "You have to fulfill your duties, but you are free. The publisher doesn't edit. It is a matter of trust. When you have a good team, you trust it. All our [Soviet] editors-in-chief trust only themselves. They change your words and they change your opinions. There is self-censorship in our journalism also. I wish I could preserve this sense of freedom back home: this is my article, my opinion and go to hell."

In a booth at the Triple Restaurant in East Hartford, Victor spies a favorite tune on the tabletop jukebox and fishes for some change. We have just taken a tour of the Mark Twain House, but it is this twangy hillbilly song that lightens up his face for the first time all day. It's a lament from long ago by Hank Williams:

"There's a tear in my beer 'cause I'm crying for you dear

You are on my lonely mind

Into these last few beers I have shed a million tears

You are on my lonely mind

I'm gonna keep drinking 'till I can't move a toe

And then maybe my heart won't hurt me so."

Victor is back home now. He gave my two-year-old son, Jackson, a Soviet transistor radio. I gave him a tape with "A Tear in my Beer" on it. In our last conversation he insisted that Jackson needed a little sister. He hoped to get a week off upon his return to take his family to their dacha in the country. He was looking forward to it even though he admitted that the lake nearby is "a little bit polluted and there are lots of cans and bottles in the forest." I said that we have that problem here, too.

He replied, "Nobody cares, David, that's how it is."