Are We Getting Zippy Yet?

Humanity can be divided neatly into two categories. Them that gets Zippy the Pinhead, and them that don’t. The legion of the latter can be refined further. Most simply pass over the non-conformist comic strip for the infinitely more predictable Beetle Bailey or Garfield; the rest get miffed at Zippy and his creator, Bill Griffith, who draws in blissful obscurity from his home nestled in the thickets of East Haddam, Connecticut.

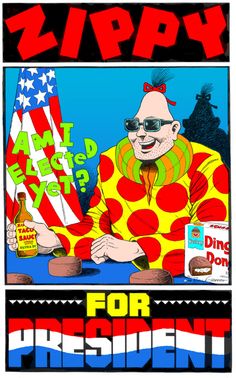

Wrathful readers can froth over Zippy in the comic pages of The Hartford Courant. Their pique is understandable. After all, Zippy is a fugitive from those anti-establishment underground comics that oozed out of San Francisco in the 1970s. He’s a deformed, self-described “bumbling surreal oaf” who sports a polka-dotted muumuu, a red bow atop his cone-shaped head, and (like Nixon) a perpetual five o’clock shadow. Zippy freely admits to delivering incoherent ramblings — rather than de rigueur cartoon punch lines —like it was his job, which it is. His spawn are named Meltdown and Fuelrod. His favorite meal is Ding Dongs smothered in taco sauce.

Need more? Zippy readers must be ever vigilant for:

• Devilishly hard word like “toroids:” mal mots whose dense dictionary definitions frequently fail to enlighten – so here’s the vernacular: “All donuts are toroids, but not all toroids are donuts.”

• Obscure references to expired beat poets, dead philosophers and the theme songs from ancient sitcoms like "The Patty Duke Show."

• Non sequiturs that can cure male pattern baldness. The strip's serious adult character, Griffy (modeled on guess who), says to the preternaturally adolescent Zippy, “You know what Kierkegaard believed, don’t you?” The Pinhead replies, “That pickled herring is fine as an appetizer but don’t try to tell me it’s an entrée!”

Even people who like strip — and its fans are hardcore — concede that the Zippy the Pinhead is an acquired taste with inherently limited appeal. Creator Griffith himself, through his cartoon persona, says he prays “everyday for limited popular acclaim.” Well, he has succeeded beyond his wildest dreams. He doesn’t draw Zippy to conform with the increasingly sketchy artistry of his peers (some actually outsource the chore), dumb the strip down, or otherwise allow crass marketeering to gain the upper hand (no Zippy movie yet or product endorsements, just the occasional regional theatre production). His idiosyncratic characters remain steadfastly true to their eccentric selves. They may pun shamelessly, but they don’t pander. Love them or leave them for Hi and Lois.

What is perhaps most remarkable about counter-culture Zippy, suggesting that the world may be as surreal as his strip alleges, is that he is published in scads of big city newspapers nationwide, like The Boston Globe and The Washington Post. More than 10 million readers a day have the opportunity to put some zip in their morning routine. What’s more, the strip is bigger than Garfield, literally. Because of the intricacy of his artwork and the amount of dialogue, Griffith demands more space than his peers have been reduced to. And he gets it. In The Hartford Courant, Zippy is a third larger than that lazy, infernal feline, who several years back flat out stole the line for which the Pinhead is most famous — he’s even immortalized for it in Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations:

“Are we having fun yet?”

Griffith and his characters get their jollies skewering the likes of Garfield, Chuckee Cheese, Steve Martin’s cloying family comedies, Homeland Security (gasp!), the fifth food group (preservatives) — just about anything that litters the post-real modern American landscape of spin, hype, legalized fraud, mass marketing, “reality” TV etc. Those zippy non-sequiturs actually have a point. You see, Zippy doesn’t believe in God, he believes in Nancy and Sluggo. When Satan pokes him with his spear, the Pinhead is unafraid because, he explains, “Rush Limbaugh is the Devil.” The cat is out of the bag, Zippy and Griffy are unreconstructed nor-eastern Liberals (more gasps). During the Terry Schiavo crusade [to keep alive a woman in a vegetative state], Zippy can be seen compulsively slicing zucchinis and cucumbers in a food processor; Griffy observes “You may have slipped into a Persistent Vegematic State!!” Zippy replies “At last!”

For all his left-leaning anti-establishment quirkiness, Griffith is considered by many observers to be head and shoulders above his more popular peers. His strip’s high artistry and relevant content stand out on a page dominated by formulaic fluff and draw-by-numbers scribblers, according to many critics like Time magazine’s Andrew Arnold. The legendary R. Crumb says flatly that Zippy is “the only comic strip in the world that I like.” Gary Groth, founding editor of the Comics Journal also finds Zippy hip.

Bill Griffith, 59, wasn’t having fun yet growing us in Levittown, New York, of all places, that epithet for dreary post-World War II conformity. His father was a career soldier. “It was a great place to escape from and I’m grateful to it,” Griffith explains. “It gave me something to fight against. It showed me what I didn’t want to do and didn’t want to be.” Helping him make his getaway were his mother, who supported his artistic stirrings, and next door neighbors Ed and Carol Emshwiller. Carol, now in her 80s, is a novelist and her late husband was a science fiction illustrator, filmmaker and academic. He and young Bill worked on quirky film projects together.

In 1962, Griffith’s great escape progressed further when he entered Pratt Institute for Art to become a serious artist. He even had a few gallery shows, but something didn’t feel right. A fellow student who was heavily into comic strips planted a seed in Griffith’s disaffected mind: all art is art, but some art is more fun. This seminal notion would germinate over the next few years, during which Griffith quit Pratt, took the grand tour of Europe, and labored at menial jobs, wondering all the while what he could possibly do to make his way in the world.

On the boat to Europe he struck up a friendship with another passenger, Jonathan Buller, who had just been suspended from Columbia University. Comic serendipity was once again in the air. Buller, too, was a refugee from Levitttown (they had gone to different high schools and had never met before), an artistic soul who would encouraged Griffith to give the comics genre a whirl. “After we got back from Europe, Buller and I were both living in New York City and he challenged me to do a comic strip,” Griffith recalls. “My art was already tending that way on its own, and I figured how hard could it be to get published in an underground weekly?”

The editor of the East Village Other was “toking away” when the freelance cartoonist delivered his unsolicited drawing, and upon viewing it exclaimed, predictably enough, “Far out, man.” The next month Griffith struck again, debuting in Screw Magazine, and he was hooked: “I remember walking into the Screw office to pick up two dozen copies of the issue with my cartoon in it, and I asked the guy how many papers they printed: he said 10,000. I never had twelve people look at my art before and this thrilled me. That’s when I stopped painting. I just stopped.”

The cartoonist would not give birth to Zippy until the early 1970s, after he moved to San Francisco, where R. Crumb of Zap Comics was pioneering underground strips replete with sex, drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll, not to mention radical politics. Griffith and another cartoonist started their own magazine, Arcade, and while the living wasn’t exactly easy, doing art beat the dickens out of suffocating in an office.

Griffith and Zippy came up for air, or more precisely were plucked from the underground by William Randolph Hearst III, who had just inherited The San Francisco Examiner. The strip was then running in the Berkley Barb, among other obscure weeklies, as well as the more prestigious National Lampoon.

“Hearst hired me and I thought he wanted me to do it weekly,” says Griffith. “When I realized it was every day, I told him I needed six months to gear up.” The serendipitous ascent continued when the syndicate King Features offered to take Zippy national. “My first impulse was to sabotage the whole deal by making crazy demands,” says Griffith, who gave it the old college-drop-out try. King agreed to everything, the money, the tumescent strip, even ceding the copyright for the original artwork, which can be purchased, along with other Zippy paraphernalia, at zippythepinhead.com.

The web site, Zippy’s lone concession to crass commercialism, is full of helpful icons to click like “strip search.” There are also thoughtful articles on the cartoon genre and electronic reprints of Griffith’s other artistic credits — including the “cartoon journalism” pieces he did for The New Yorker magazine in the mid 1990s. The site even has a reader tutorial section, a six-step program to fathoming Zippy.

After more than three decades of cartooning, Griffith now can do it daily with relative ease. He is still published in The San Francisco Examiner and about 200 other aboveground newspapers — not as many as Garfield, but about 185 more than he ever thought he’d be in.

Bill Griffith and his wife Diane moved from San Francisco to rural Connecticut in 1998. Both of their parents had lived near them in California and passed away during a trying emotional period in the mid 1990s. The couple felt it was time for a change of scenery. One of the reasons they chose rural East Haddam was because of Jonathan Buller, who also became a cartoonist and now writes and illustrates children’s books in nearby Lyme.

“The move was a big creative shot in the arm for the strip and this wasn’t planned” Griffith says. “In a new place your eyes open again. I don’t know why exactly but I started to travel around more, to notice where I was more.” One of the hallmarks of his strip has always been “roadside attractions” — picturesque diners, architectural oddities and bizarre commercial icons, such as the giant muffler man. For Zippy, Connecticut was a whole new world to explore and wax surreal in. In Norwich he engaged a humongous bowling pin in philosophical ramblings, while Griffith uses the frosted layer cake architecture of Hadlyme’s Gillette Castle as a backdrop for many strips. A field trip to (sur) Real Art Ways in Hartford was inevitable.

The whole Nutmeg angle has lead to a new subdivision of Zippy readers: them that think they get it. After a series of strips set at O’Rourke’s Diner in Middletown, The Middletown Press bought Zippy only to find that the Pinhead quickly migrated to other picturesque and far-flung locales. In addition to ideas derived from his own travels, Griffith has shoeboxes stuffed with photographs of roadside curiosities that his loyal readers send him. The paper has since dropped the strip.

Fellow artist Jonathan Buller is among those who get Zippy. “It’s not a joke like you’ll see in Blondie. It’s a kind of wit that has a purpose. It’s never just scrambled eggs. Once in a while I don’t get a particular reference, but Zippy is completely comprehensible to me.” He refers to a recent strip where Zippy and a fallen roadside commercial mannequin are lying on their backs singing TV theme songs. Zippy is belting out the upbeat lyrics from the Patty Duke Show and his inanimate playmate is crooning the Sopranos’ dark requiem. “These two lunatics are on their backs singing TV theme songs,” says Buller. “I find that kind of funny. It’s not a joke that you’re going to be slapping your knee over.”