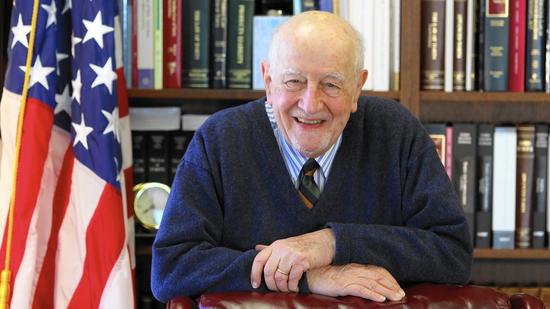

The Honorable Guido Calabresi

[Link to original story in New Haven Living and photos by Stan Godlewski]

Guido Calabresi, who is 83, continues to do many-splendored things.

He is a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit, one step below the Supreme Court. He is a professor at the Yale Law School, where he began teaching in 1959 and which he led as dean from 1985 to 1994. He is a distinguished scholar credited with co-founding a new field of law that bequeathed to the world, among other benefits, the concept of no-fault accidents. His latest book on torts is coming out shortly while several others are percolating in his fertile mind.

The Honorable Guido Calabresi — who beseeches one and all to "Call me Guido" — has taught two of the current members of the Supreme Court and was instrumental in getting a third justice a job after law school.

Not incidentally, he and his wife, Anne, are purveyors of their very own olive oil, from their hilltop grove in Tuscany; they share the harvest with friends and family. The couple's three children have excelled in their respective fields: medicine, academia and journalism.

If America has been very good to the Italian-born Calabresi, he and his family have returned the favor, with interest. He and Anne are involved in numerous community endeavors in New Haven, and he even served two terms as selectman of their hometown of Woodbridge. In some ways the two could not be more different. His ancestors are Italian, Catholic and Jewish; hers are English Protestants who were present at the birth of the Connecticut Colony.

"You can't talk about Guido and New Haven without talking about his lifelong collaborator, Anne Gordon Audubon Tyler Calebresi," says Norman Silber, who is conducting an oral history project on him at the invitation of Yale. A senior research scholar at the Yale Law School and law professor at Hofstra University, Silber adds, "The two of them are rooted in Connecticut. Both are extremely generous with their time, he in particular with his students. It's quite clear when you're talking to Guido that he is paying extraordinary attention and cares deeply about connecting with the person who is in front of him."

For all his erudition and achievements, Guido Calabresi describes himself first and foremost as a refugee, an immigrant — and, most strikingly of all, as a beneficiary of affirmative action. He came to America at age 7 in 1939 with his parents, who had long opposed and finally fled Mussolini's fascist rule in Italy.

"When I am asked what the most important part of my legal education has been, I tell people that I am a refugee, an immigrant," he says. "We came here without a penny. Being an outsider shaped me, it made me more empathetic. I was sworn in as a judge on the 55th anniversary of the day I landed in this country. I wanted to show all that America had done for me and why I am a patriot. I mentioned the people who helped me. I was given affirmative action. It is nothing new. It has always been given. People only make a fuss about it today because it is given now to African Americans. I was offered positions because I was Italian American."

Calabresi clearly took full advantage of every opportunity afforded him. He graduated from New Haven schools, attending the Foote School on a scholarship, where he met Anne, and then Hopkins School. He was summa cum laude at Yale in economics and a Rhodes Scholar — first in his class at Oxford. He was first in his class at the Yale Law School — after which he clerked for Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black.

Harold Hongju Koh, also the son of political refugees, speaks of his colleague and friend with an affection bordering on beatification. In 1962, Calabresi was instrumental in getting Koh's older brother admitted to Hopkins, which later accepted Harold as well. Harold Koh, who a la Calabresi rose to become dean of the Yale Law School and is now its Sterling Professor of International Law, states flatly, "There is no one like him in any law school in America, and there never will be."

The Italian Flag, And A Bobblehead Doll

Koh recalls an incident that illustrates the bond Calabresi forms with his students: "For his birthday each year they keep trying to come up with ways to fool him. One year all of his students dressed in the colors of the Italian flag. Some wore green and sat together in one section and others were in all red or white and were grouped in two other sections. So Guido is teaching to a room that has become a giant Italian flag. When he figured it out, very quickly, everyone just cracked up."

Calabresi's downtown New Haven office is a sprawling well-windowed complex on the 18th floor, with sweeping views of the city and beyond. One wall is decorated with candid photos of the law clerks from his 21 years on the bench, virtually all of whom have gone on to have impressive careers. As the tour continues, a current law clerk passes by whose attire can only be described as "clambake casual." A Bobblehead Doll of the boss in his robes presides over the reception area. One assistant's desk is spare and well-ordered; another's looks like the Augean Stables. The message is clear: As long as the work gets done, to each his own.

Peaking out from behind the judge's desk is a pair of circa 1970 sneakers, which he dons when he exercises on the carpet. He had a coronary bypass operation within the past year and wears a hearing aid. But his face and hands look remarkably young. He is like a favorite uncle, the one brimming with kick-ass stories. National Public Radio ranks his commencement address to the 1988 graduating class of Connecticut College as among the best ever.

A Scathing Review Of Rehnquist's Court

Courtly persona aside, Calabresi isn't afraid to mix it up. In 1991, while still dean, he wrote an op-ed piece defending controversial Supreme Court nominee and Yale Law grad Clarence Thomas, whose legal mind, he insisted, was first rate and whose humble upbringing would contribute an important perspective to that august body. He also noted that he was a Democrat and a liberal and that he differed with Thomas on issues like affirmative action.

The article was written prior to the allegations made by Anita Hill, and it included a scathing review of the nation's highest court, which was led at the time by Chief Justice William Rehnquist. Calabresi wrote that he "despised" Rehnquist's court, finding "its aggressive, willful, statist behavior disgusting — the very opposite of what a judicious moderate, or even conservative, judicial body should do."

The broadside may have cost him a chance to become U.S. solicitor general, who argues cases before that "despised" court. Three years hence, in 1994, President Bill Clinton named him to his current position on the 2nd Circuit Court, whose rulings were subject to review by Rehnquist et al.

In 1998 one of his students, the daughter of immigrants, joined him on the bench. Now a Supreme Court justice, Sonia Sotomayor thinks highly of him: "Guido is not just brilliant but a caring and giving human being. He is a loyal and supportive friend, colleague and mentor.It is always so much fun to listen to him think through a problem out loud.He is humorous yet so very deep in his analysis."

Friendships notwithstanding, Calabresi is still critical of the Supreme Court, if less impolitic: "I would never say today that I despise the court, but yes, I am very critical of it. There is a reason I think that the court has many problems and that is — it's an odd reason — too many justices of the court have come from the same kind of background. Almost all have been court of appeals justices. It's good training, it's important, I am one myself, but it causes them to see things too much from one point of view."

He proceeds to conjure another era, when the Supreme Court had a different makeup: when it voted unanimously in 1954 to strike down segregated schools. He reels off the names of the nine justices from that time, headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren, highlighting the diversity of experience that each member embodied, from politics and administration to academia and trial law.

"You had people bringing in different parts of the law, so they listened and talked to each other because they knew that each brought something of value to consider," he says. "I believe the courts are becoming and have become too political. But in fact our court, the 2nd Circuit Court, is not that political, it's not an ideological court."

Judge Richard C. Wesley, who terms himself "a moderate conservative from upstate New York," has served with Calabresi on the bench for the past 12 years and says that he and his "left of center" colleague agree on the law: "We have sat together on three-judge panels and have not dissented from one another yet. I would guess in at least 300 cases. … He's enormous fun to be with. He remains joyful about life and about what he does."

In addition to being a judge, scholar and teacher, Calabresi is no slouch as an administrator. Harold Koh and many others credit him with resuscitating the Yale Law School after taking over as dean in 1985, elevating it to its perennial position as being regarded as the best in the nation. "It was on the precipice when Guido took over and he brought it back by his sheer energy and his outreach to everyone," Koh says. "There was a financial crisis and the building was falling apart. He talked every day about humanity and excellence, that we can't be excellent at the cost of humanity; that is still the pervasive value of the school and what distinguishes it from everywhere else."

Legal theory is all well and good, but the law ultimately is about people, according to Calabresi, who expounds on more than torts in his classes. "I tell my students two things make for a happy life: Find something to do that is fun and useful, which is what I have been lucky enough to do, and find somebody to spend your life with. Anne and I have been married for 54 years. She is an incredible person, an amazing, amazing person."

Guido Calabresi is no piker himself and he is still having fun. To the obligatory question about retiring, he responds with a question: "Why would I do that?"