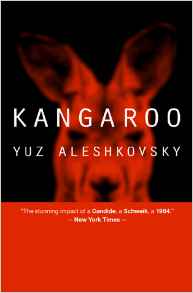

A Russian Novel

Underpinning the continuous fantasies that embody "Kangaroo" is a powerful satiric allegory worthy of George Orwell's "Animal Farm." The more the novel's protagonist, Fan Fanych, feels a growing empathy with animals, particularly those caged in zoos, the more he is oppressed by his Soviet keepers.

Fanych frequently proposes that he and his friend Kolya (to whom the book is narrated) toast members of the animal kingdom: "Let's drink to anteaters and armadillos, who yearn for their native jungles forever. God give their children freedom someday, or at least their grandchildren."

Like the author, Yuz Aleshkovsky, a Russian emigree who spent time in the Gulag, Fanych is an independent-minded Jew, an a priori criminal stoically awaiting an offical charge. When he is finally called in by the KGB in 1949, he has a choice of 10 crimes to be accused of. Possessing a flair for the dramatic, Fanych picks this one: "That he did, on a night between July 14, 1789 and Jan. 9, 1905, bestially rape and sadistically murder in the Moscow Zoo a Royal Holstein kangaroo answering to the name of Gemma . . . "

His trial, as might be expected, is a phantasmagoric journey into the unreal jungle of the Soviet legal system. Having first made up the crime, the authorities must now concoct the evidence: Fanych offers to write a screen play for the movie that will convict him. Instead of allegedly duplicating life, Socialist Realist art has become reality. The defendant finds himself caught up in his own propaganda. As the film rolls on, he begins rooting for the state and against himself.

After the show trial, parasite Fanych is sentenced to a labor camp containing purged comrades of Lenin, sad old Bolsheviks who, despite their cruel fate, still cling to their faith in the inevitable worldwide triumph of Soviet communism. They have risen above their individual tragedies, seeing themselves as martyrs to the cause of Historical Necessity. Isolated from the world — even from state disinformation — they cheer wildly when Fanych tells them that Winston Churchill is being tried in the Moscow City Court. In a nation built on unreality, their little sphere is simply more unreal than others.

During his incarceration, Fanych reminisces about the time he happened upon the meeting of Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill at Yalta in 1945. Hidden in the basement, he looks out through a grate and can see only the feet of the world's great leaders. At one point, he is observing Stalin sitting alone when the dictator's own right foot starts a rebellion: his unruly body part declares, "Hey, Stalin. You`re an (expletive deleted)!" The self-abuse continues and the leader of world revolution ponders his choices. A foot's not a conscience, so he can't shut it up. Amputation is a possibility but then, "Can you rely on the left foot?" The answer is no, of course, when enemies and traitors are everywhere.

Fanych is eventually freed, after Stalin's death, and returns to Moscow to look up his KGB prosecutor. He is nowhere to be found and there is no record of his ever having existed. There is also no record of Fanych's bestial crime. He goes to the zoo and determines that a kangaroo named Gemma actually had been murdered. He wishes that the animals in the zoo and the people of the Soviet Union might one day be free of their unnatural worlds. Like a zoo, Fanych concludes, the Soviet state is a crime against nature; and "The world doesn't forgive men who try to turn it inside out."

Some readers may not forgive Aleshkovsky for his flights of fancy. At times, his magic-carpet rides are too long or simply without redeeming significance. Also, the novel was written in 1975 in the Soviet Union for a Russian audience, and therefore many of the indigenous references will be lost on Westerners. Still, "Kangaro" will reward those who persist through these stretches. Delivered with a searing and insightful wit, Aleshkovsky's message is universal and compelling: humankind should be free, or at least struggling to be so.