History in a House

It’s an extraordinary trek that Mac Griswold guides the reader on, less of distance than through time, beginning in the infancy of the America, before we were one nation, when our ancestors — white, black, and Native American — were defined as much by who they weren’t as by who they were.

The trip begins in a rowboat mirroring the coast of Shelter Island, an idyll nestled between Orient and Montauk points on Long Island’s east end. It is here, in 1984, that the author and her main character, a grand 18th-century manor, meet: “The reflection of the house in the glassy water doesn’t tremble. No wind. I hold my breath, too, as if the building would disappear if the water moved…. This place isn’t self-consciously ‘historic;’ it’s not restored in any sense. It has simply been here, waiting for time to pass. Waiting for me.”

No one is home that day, but Griswold writes the owners several times, finally gets an answer, and returns to the house to meet Alice and Andy Fiske, he being the fifteenth member of the founding family to live on the property stretching back to 1652.

They are a nice couple, the kind that dress up to go to the Post Office, but on the manor tour a sordid piece of family laundry is aired: Andy points matter of factly to the “slave staircase,” narrowing winding steps that lead to a cramped, drafty attic long since closed off. He had been talking about the “servants” who had built his circa 1735 house, and it is now clear that the term is an egregious euphemism.

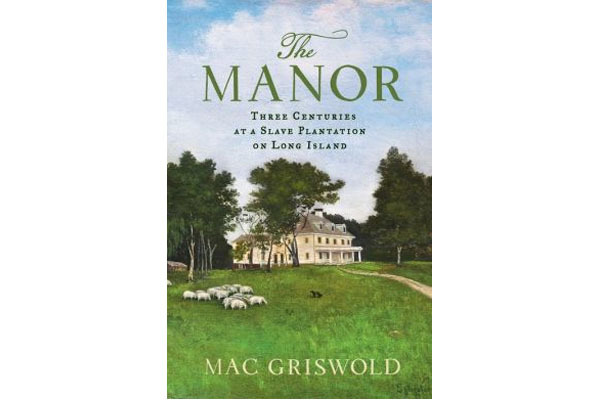

At that moment "The Manor: Three Centuries as a Slave Plantation on Long Island" is conceived, but the gestation period is long. The author of several books on gardening and plants, Griswold also has written for newspapers such as The New York Times. With Alice Fiske’s generous support (Andy had passed away) Griswold returns in 1996 to research the manor and grounds. The project would continue off and on for a decade.

She is a landscape historian and engages archaeologists, architectural historians, local history buffs, and even a dowser to help her unlock the past: where the buildings tumbled down and where the Indians lived before and after the whites took over; forgotten cemeteries; and onetime gardens and fields — where slaves had tended crops and animals to be shipped to the West Indies to fed fellow slaves there.

Northern slave culture was distinct in many ways from its counterparts elsewhere by nature of the land, climate, and agriculture. Farms tended to be smaller and more diverse in what they produced than sprawling Southern and Caribbean plantations, and their workers needed to master various skills or trades to be productive. They were, therefore, not as expendable or as numerous, but they were slaves just the same; America’s “peculiar institution” was not peculiar to the South.

In 1680, family patriarch Nathaniel Sylvester listed 24 human beings among the many “possessions” in his will. They had contributed greatly to his considerable wealth. New York State did not completely abolish slavery within its borders until 1827. Slaves were never compensated for their suffering or for the work that they did.

The number of slaves on the island would gradually diminish, and Nathaniel’s tribe, like the Indians, would resort to land sales to make ends meet. Familial continuity on the island, which now [2013] stands at 361 years, often was in doubt. But, in the nick of time, a prosperous scion or a well-heeled spouse would appear to save the day, to keep the estate stately and solvent. The most recent example is Eben Fiske Ostby, Andy’s nephew and a co-founder of Pixar. Much of the family land is now in conservation easements and a nonprofit educational farm operation has been established.

The reader should know up front that this journey is not always easy or confined to one small upscale island. This is no breezy survey. The author’s mission is ambitious and she is attentive to telling and even minute details. It encompasses glaciers, the English Civil War, diverse and obscure flora, Barbados, West Africa, Amsterdam, Victorian women’s fashion (one will learn what a farthingale is, or was), and a cast of characters who are sometimes hard to place (the genealogy in the front helps). Her notes alone, in small print, consume 116 pages. There are stretches when one longs for Long Island again.

But this ambitious narrative is well worth it. The multifaceted story – albeit about a house on a small island and the mostly un-famous people who lived there – is not provincial or obscure. It is a transcendent saga about the power of history and place, about who we were as a people, centuries before, and how that identity is part of who we became. As William Faulkner noted, “The past is never dead. It's not even past.”

The author clearly was fond of Alice Fiske who, before she died in 2006, endowed the Fiske Center for Archaeology Research at the University of Massachusetts in memory of her late husband. She was a pleasant, intelligent woman without whom this book would not have been possible.

Her annual Christmas party at the manor was a grand occasion, with guests of all descriptions and walks of life. But they were all white, including the director of the local historical society, whose husband is black and Native American. Alice did not invite him.