Where's the Beef?

The story of McDonald’s is a quintessential American saga — it could be subtitled the life, rather than the death, of a salesman. Ray Kroc, a high school dropout and the son of immigrants, not only conquered the fast-food world, he started his assault when he was well into his 50s and wouldn’t taste success for another decade.

In 1961, with a $2.7 million loan, he bought out the two brothers who had started McDonald’s and began to run the company his way. With fewer than 1,000 franchises under his belt, Kroc took McDonald’s stock public in 1965 and became an instant millionaire, 33 times over. Today there are more than 36,000 McDonald’s worldwide.

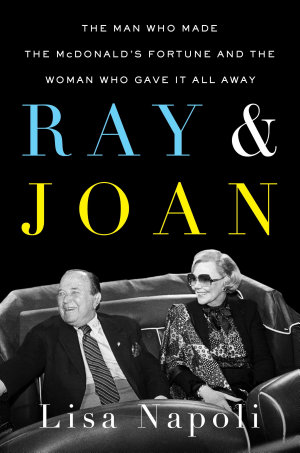

That last numerical nugget is one of the many things readers won’t find in the surprisingly cursory duel biography, Ray & Joan: The Man Who Made the McDonald’s Fortune and the Woman Who Gave It All Away (Dutton, 266 pp., ** out of four stars). It's not that author Lisa Napoli, an experienced journalist, hasn’t done considerable research or doesn’t cover the basics. She simply leaves things out that would have enlivened her narrative.

The first page is tantalizing enough, with the promise of a peek inside the gated world of those devil-may-care “one-percenters.” Ray Kroc apparently would fire people — actually, have his secretary do the honors — for drinking the wrong cocktail. “Manhattans, he thought, were for sissies,” Napoli writes. Joan, Ray’s third wife, also had an underling discharge “a once-beloved cook who deigned to ask for a modest raise after years of service.”

But thereafter the book settles into a fairly humdrum tale that offers little that is new or particularly insightful. Ray was a workaholic and a high functioning alcoholic, and he and Joan had some real donnybrooks. These are not explored in any detail, even though Joan once filed for divorce citing physical and mental cruelty and obtained a temporary restraining order against her husband. The couple reconciled.

We learn that Ray was a "staunch conservative," that he ordered, for example, the flags at all McDonald’s to fly at full-staff after four Kent State students were killed by National Guardsmen in 1970. He gave more than $250,000 to Richard Nixon’s 1972 reelection campaign, but then the trail goes cold.

Joan, on the other hand, was a liberal, something she hid from the world until after her husband’s death in 1984. In addition to embarking on a life of laudatory philanthropy, the widow gave $1 million to the Democratic Party in 1987 and $3.6 million to the Carter Center. (If she gave another penny to the Democrats before she died in 2003, the reader doesn’t find out).

“St. Joan of the Arches” was, indeed, a godsend to myriad causes, from National Public Radio to the Salvation Army, which alone received more than $1.5 billion (yes, billion) from her. She gave most of her fortune away; this is documented in too much detail.

Joan Kroc, the author cautions, was not a saint. But rather than explore her complex personality, Napoli only provides bromides, such as, “She had a bawdy sense of humor, and she smoked like a fiend.” An example of an off-color joke would have been most welcome at this point.

The reader is left with many questions about Joan and Ray, who smoked and drank too much.

Maybe we'll learn more from The Founder, the movie starring Michael Keaton as Ray Kroc. It's set to open in New York and Los Angeles on Dec. 16 and nationwide on Jan. 20.