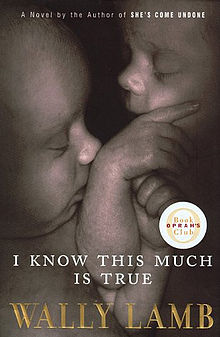

Wally Lamb's 2nd Novel

Wally Lamb’s second novel, "I Know This Much Is True," has outdone his bestselling first, and that's going some. The latest by Norwich Free Academy’s best-known former teacher is an epic tale of love and hate, good and evil, tragedy and triumph, all set mostly in the eastern Connecticut mill town of Three Rivers (which any local yokel with a GED diploma will determine is Norwich before reaching page two.

Lamb’s prose is vivid and engaging. His characters are wonderfully diverse. He moves effortlessly from Norwich circa 1990 to 19th century Sicily, bringing both places and their inhabitants to life. Then, little by little, he makes the connection between the two, weaves the thin, subtle threads that bind these disparate places and people together.

While most of the scenes are close to home — familiar names and places abound, some disguised, like Hewett City, and some not, like New London, for some unknown reason — the book's themes are complex and universal.

Dominick Birdsey, the son of Concettina Tempesta, is a third generation Italian-American who is down on his luck. In fact, his entire life has been something of an emotional, almost Biblical tempest. Born in 1950, he has had to contend with many plagues: a missing father; an abusive stepfather (who works at Electric Boat); a meek, hair-lipped mother who likes his identical twin brother, Thomas, best; and the difficulty of finding his own identity amid all this familial chaos. Dominick is four when he first realizes that he and Thomas are not one and the same person.

The importance of establishing a separate persona becomes all the more critical when Thomas, always a sweet but somewhat strange child, develops schizophrenia while the twins are attending the University of Connecticut. Dominick’s hope of distancing himself from his troubled brother is complicated by an equally strong urge to protect his alter ego from a hostile world.

If Thomas is getting more insane by the day, Dominick isn’t far behind. His first child has died in her crib and soon after his wife of 16 years divorces him.

He tells the psychiatrist who is now treating both him and his brother: “You want to know what it’s like for me? Do you? It’s like … It’s like … my brother has been an anchor on me my whole life. Pulling me down. Even before he got sick … an anchor: And you know what I get? I get just enough rope to break the surface. To breath. But I’m never going to …You know what I used to think? I used to think that eventually—you know, sooner or later — I was going to get away from him. Cut the cord, you know?”

There are other twins in the novel. Ralph and Penny Ann Drinkwater, of the local Wequonnic Indian Tribe (a composite exhibiting characteristics of two real life local native American sovereign nations), are another pair. They become “untwined” when Penny Ann, a third grade classmate of the Birdeys, is abducted, sexually abused and found dead below the Falls of the Sachem River.

Concettina is also a twin. Her brother was stillborn, an outcome that is monumentally disappointing to her father, who is left with no sons to carry on the family name — only a disfigured daughter whom he thinks no one will ever marry off his hands.

Many things, however, are not what they seem in and about Three Rivers. Consettina will find her love and Dominick will learn that his mother is not so meek after all.

And Thomas, for all his delusions and paranoia, is often quite sane, like the fool in a Shakespearean play. “That’s the trouble with survival of the fittest, isn’t it, Dominick?” Thomas says one day out of the blue. “The corpse at your feet. That little inconvenience.” It will take Dominick many chapters to fully appreciate this shaft of wisdom breaking through his brother’s madness.

Lamb is too astute to wallow in life’s grimness, its downright insanity, without offering interludes of humor, glimmers of hope, of salvation even. The book, after all, is 901 pages. If the reader is reduced to tears in places, in others the laughter flows like water over the Sachem River Falls.

If Lamb exhibits any less than admirable writerly qualities, he seems toward the end of his novel to be wrapping everything up, like a tidy Christmas present, for the reader. After brilliantly describing in hundreds of pages how capricious and untidy the world can be, he seems to be a little too intent on cleaning up the mess in the last few chapters.

That aside, from the very first page Lamb’s prose grabs hold and doesn’t let go. The last page arrives too soon. You feel like part of the family, like Dominico could have been your grandfather, like you might have gone to school with Dominick. The characters are as vivid and familiar as the places they inhabit.