Eleanor and Alice

First cousins Alice Roosevelt, the darling of the tabloids a century ago, and Eleanor Roosevelt, that relentless do-gooder, were not always catty rivals. Born in 1884, they became fast friends at the age of three, playing together at Sagamore Hill, the Long Island estate of Teddy Roosevelt. He was Alice’s father and Eleanor’s uncle. While Teddy had a tortured relationship with Alice, whose mother had died giving birth to her, he freely proclaimed Eleanor to be his favorite niece. Maybe that’s how the tiff got started.

Once begun, however, it would intensify over the decades, particularly as ideology and the political ambition of loved ones were thrown into the mix. But it was more than mere politics. These two were polar opposites in many ways.

Alice loved to party and gossip while she was advising Republicans in high places, albeit from behind the curtain. Her only child was not fathered by her husband, Congressman Nick Longworth, but rather by Senator William Borah (long suspected, this was confirmed when their correspondence became public in 2007). She never worked: rather she kibitzed and she skewered. Her wit didn’t spare fellow travelers: Thomas Dewey was “the little man on the wedding cake” and Calvin Coolidge looked like he’d been “weaned on a pickle.” Her death certificate listed her occupation as “gadfly.”

Eleanor meanwhile was serious to a fault, a liberal idealist to the left of husband Franklin, that purported traitor to his class. Fun for fun’s sake was frowned upon. Good works were more important than good times – often more important than her own family. As First Lady during the Great Depression, Eleanor remade that role, writing a newspaper column, holding press conferences (for women reporters only), and giving speeches on issues of the day. Despite her natural shyness, she became a leading lady on the political stage while her husband was president – and after his death in 1945 until hers in 1962.

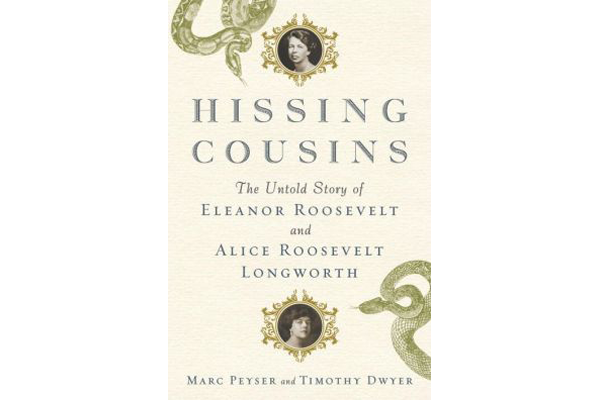

In their first book, Hissing Cousins: The Untold Story of Eleanor Roosevelt and Alice Roosevelt Longworth, authors Marc Peyser and Timothy Dwyer have brought this odd couple back into focus. It is hardly an “untold story,” but they ably have resurrected a compelling drama dimmed by the fog of time. The research is thorough and the prose is stylishly authoritative, comme ça: “They were born in the same year and neighborhood, shared the same friends, lived in the same houses (including the White one), married the same type of men. They were arguably the most famous women in the country, if not the world…One of them whispered behind the scenes and one of them spoke to audiences around the world, but they made their voices heard – and count.”

Eleanor’s place in our national heritage is secure, but Alice has faded to an unread footnote. And yet once she was “Princess Alice” in the White House, confidant of Presidents from her father to Richard Nixon, the subject of two “60 Minutes” profiles late in her life. Her White House debutante bash in 1903 was international news. She smoked. She drank. She likely danced the Hoochie Coochie. When questioned about his daughter’s behavior, Teddy replied, “I can run the country or I can control Alice. I can’t possibly do both.”

The tension between Eleanor and Alice was at once familial and political, centering on which branch of the Roosevelt tree would prevail in politics: the Sagamore Hill GOP gang or the Hyde Park band of Democrats. For all the acrimony between the two camps, Franklin and Teddy liked and admired one another despite party allegiances, and their progressive ideals were virtually indistinguishable. But Teddy’s descendants, Alice in particular, did not cotton to the Roosevelt presidential crest being passed to Franklin rather than to her brother, Teddy Roosevelt, Jr.

For all that, the cousins didn’t burn every bridge. They visited, they wrote one another, they commiserated during sad times. Alice could say the nastiest things about Franklin and still get invited to the White House.

Alice’s and Eleanor’s differences were in part ideological. The former opposed Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations and remained an adamant isolationist in the run up to World War II (a position her Rough Riding father almost surely would have disagreed with). She was Mrs. Republican, confidant to Presidents from William Howard Taft to Richard Nixon. Indeed, the first President she visited in the White House was Benjamin Harrison and the last Gerald Ford. Eleanor was Mrs. Democrat, upon whom John F. Kennedy called at Hyde Park, hat-in-hand, to win her favor in 1960. Without her support – crucial to energizing black, female and liberal voters – he almost certainly would have lost the election.

In her “60 Minutes” interview seven years after Eleanor’s death, Alice remained catty to the end, even doing her well-honed impression of her toothy cousin for a national TV audience. She may have been naughty, but she was wicked good fun. She managed to infiltrate the Kennedy White House and charmed Democratic stalwart Arthur Schlesinger, who wrote in his journal: “I would rather spend an evening with Alice Longworth than with Eleanor Roosevelt. Politics, I came to conclude, is not everything.”