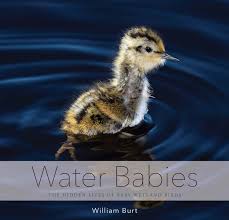

Water Babies

The subjects of William Burt's latest book of bird photography, "Water Babies: The Hidden Lives Of Baby Wetland Birds," are an astonishing lot. There is no accounting for their diversity. Downy cute ones abound, of course, but some chicks toddle across the pages looking more like dinosaurs, or mad scientists, or psychedelic rock posters, than anything else. Nature and the author, it seems, share a sense of humor.

Often great disparity is evident between mother and child. Many of the young look adopted, and odd acquisitions at that. It's an enigma to Burt, who has been observing and documenting shorebirds for more than four decades: "It is just stunning to me that the young can have an entirely different design; I don't quite understand it."

Many of the most riveting photos in the book (W.W. Norton/Countryman, 352 pages, $29.95) — there are more than 220 portraits of 43 species — are those that capture parent and offspring together. The images of tiny grebes "ferry-boating" atop mamma's back are perhaps the most fetching of all, although the wee black-necked stilt gazing up at mom's chic pink legs is in the running. Almost every page holds a surprise.

William Burt's 'Water Babies'

Western grebe mother and passenger. (William Burt)

From his teenage years visiting his grandfather in Old Lyme, where he now lives, Burt has been fascinated by the mystery of birds. The more elusive the species, the more he is attracted to it. By way of explaining his life's singular passion, he writes in the introduction that long ago "a strange unbirdlike bird stepped out before me" and proceeded to skedaddle back into the marshes. He followed it, and thrashed about in the reeds to no avail.

Burt was 14 years old, and he has been following birds ever since. He goes to the most extraordinary lengths to find and photograph them, whether along Connecticut's shore or more often in watery locales like Saskatchewan, North Dakota and the Everglades. In the wildest places, he hires a person with a gun to watch his back.

Burt doesn't do backyard robins or osprey on manmade nests. He shoots birds that are rarely seen and the most challenging to capture on film. He spent more than a decade pursuing reclusive rails, like the one that eluded him as a boy, for his 1994 book "Shadowbirds."

Bird Photographer William Burt

Photographer William Burt of Old Lyme is known for his extraordinary shots of rarely seen birds. He has a new book “Water Babies: The Hidden Lives Of Baby Wetland Birds'' (Provided by W.W. Norton Co.)

His combination of perseverance and skill has earned him rave reviews from his peers and prominent naturalists, among them the late Roger Tory Peterson, the founding father of modern American birding. Burt and Peterson, who also lived in Old Lyme, became fast friends, and this book is dedicated to Peterson's memory.

Burt's photos, often accompanied by his prose, have been published in national magazines and exhibited widely. A selection of his "Water Babies" photos is on display at the Connecticut River Museum in Essex through Oct. 12.

Burt's latest opus, his fourth, encompasses several accessible species, such as piping plovers and snowy egrets, but the fieldwork still took him seven years to complete. He knew from the start that baby birds would be elusive quarry. There was a degree of difficulty involved in finding their nests during the small window of time, a week or two, when mother and chicks are together and being decidedly reclusive.

Surprisingly, Burt discovered that the most elusive species for his book happened to be a Connecticut regular — the elegant black-crowned night heron: "They're common here, sure, but where do they nest? They nest on offshore islands and in certain swamps and normally their nests are very high up and inaccessible. I didn't even know what a young night heron looked like."

William Burt's 'Water Babies'

Black-crowned night heron young sounding the alarm. (William Burt)

So he put the word out on the street to his network of birders and biologists throughout the continent. The call came from a woman in North Dakota who knew of an island in a remote prairie marsh where the birds nested in shrubs. Burt packed his car full of his makeshift gear, including the "floating blind" he built himself, and headed west.

"The island was full of night heron nests, these baskets full of the most God-awful-looking creatures you've ever seen in your life," he recalled. "Each nest was a madhouse. The chicks looked insane, lunging at me with their wild yellow eyes."

Stalking His Subjects

The jumble of young herons is, indeed, a sight, one that inspires equal parts laughter and wonder. The mother is like a Shakespearean sonnet; her young are a gaggle of bad puns.

Even when Burt located the heron colony, the dance was just beginning. To get the intimate, richly detailed images that fill his books, he has to get close, ideally within 10 feet of his subjects. He does this on foot or from stationary blinds, but there are times when he spends five hours belly-deep in cold water, stalking skulking birds from his floating photo lab.

William Burt's 'Water Babies'

A piping plover chick in full stride at Old Lyme beach. (William Burt)

Other places, like Old Lyme, are more convenient, but his photograph of a running piping plover chick on Griswold Point took nearly 500 shots until he was satisfied.

The results clearly justify his extreme effort. His photographs provide a wormhole into a parallel universe that hardly any of us will visit, or even if we did, could see as Burt does.

Not prone to proselytizing, Burt has seen great changes in the decades he has been prowling wetlands. Black rails, the most elusive of all his subjects, used to infest the Maryland marshes but are now gone from there, a development he called "devastating." Closer to home, on Great Island in Old Lyme, spring and summer are not silent, but they are less noisy than before: "I was out there several weeks ago and you don't hear rails calling and there are many fewer salt marsh sparrows out there. It's a quieter place. It seems that there are far fewer of the marsh birds nesting there. It's pretty striking. That's my impression. I'd guess the cause is sea-level rise."

Burt's new book is a paean to what we have not yet lost. It is humbling to see the richness of the world we share with such ethereal creatures. And although we might rarely see them, it is clear we hold them in the palm of our hand.