Jerky Jocks

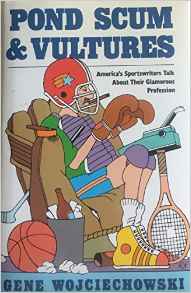

As if it isn`t enough warning that this is a book by a sportswriter about sportswriters, its first line, which ends with a period, is not a sentence. It reads: "About the title." Author Gene Wojciechowski is clearly proud of his title (an insult tossed at him by a professional athlete) and his book. He is already dreaming of a sequel. This is unfortunate, because a little pond scum goes a long way.

The book consists of incident after incident in which jocks are allegedly jerks to sports journalists (the last term, some would insist, is an oxymoron). The author gets his tales from 130 fellow scribes and maintains that each and every account is "totally true." Reaching this rarefied plateau of veracity is akin to athletes who give 110 percent 110 percent of the time.

Heres a typical case of scribe abuse. In 1989 a San Diego Union reporter approached ornery quarterback Jim McMahon after a game. McMahon clearly didnt want to talk. But the sporting public has a right to know, so the intrepid journalist persisted: "What about the problems the team's been having in its two-minute offense?" The gridiron star remained Sphinx-like. "I didnt hear your answer," the reporter said after a pause. McMahon then replied, in a fashion; he blew his nose at the reporters shoulder.

Are you ready for the sequel yet?

For some reason, the author believes that his readers will be astounded at tales of boorish, lewd and menacing conduct by the Jim McMahons of the world. This book is really a spinoff of Art Linkletters Kids Say the Darndest Things. Only in this case the kids are fully grown (physically, at least), rich and slightly better educated in most cases than Linkletters subjects.

In fact, after following the puerile antics of George Steinbrenner, Darryl Strawberry, Pete Rose and their ilk, very few Americans will be surprised by Wojciechowski`s revelations. Twenty years ago Jim Bouton established in "Ball Four" that our sports heroes, like Mickey Mantle, were not exactly Supreme Court material, much less the sort of people whom we would want our children to emulate.

What the author could have addressed if he wanted to write a more thoughtful book about his profession is what exactly is the role of sports chroniclers. Are they, in truth, journalists? Or are most of them simply publicists for big-time sports? For example, the American press covers games like the Super Bowl far more comprehensively than it does more weighty matters, like the savings and loan scandal.

It would be interesting to compare how much money a paper spends on its sports department versus what it budgets for state capital coverage.

Forgiving the fact that the author has taken the easy, anecdotal route to royalties, "Pond Scum" is different for its obvious bias against jocks. Many athletes are polite beyond imagining to the right-to-know possees which shadow them for half the year. For every jerky Jim McMahon, there are probably a dozen athletes with the patience of Job, accommodating types who answer questions like, "How does it feel fumbling away the Super Bowl like you did?"

"Pond scum" may not be a fair epithet for the majority of sportswriters but it sums this opus up fairly well.