The Real Count of MC

Most of us will depart this vale of tears little noted beyond our immediate circle of friends and family. The obituary in the local paper will be paid for, and our headshots will not live on in Webster’s Dictionary. Within a few generations, all conscious connections to the living will vanish. How many of us can name our eight great-grandparents?

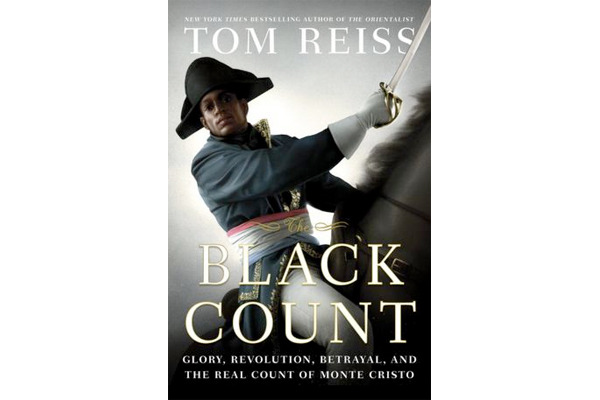

Sometimes even quite remarkable people rapidly dissipate into the murk of eternity. In his second book, "The Black Count: Glory, Revolution, Betrayal, and the Real Count of Monte Cristo," Tom Reiss has resurrected one such lost soul, offering him up to us in all his swashbuckling relevance.

Alexandre Dumas would lead what can only be described as two fictional lives. The first was his own improbable saga: up from slavery in Haiti to the rank of general in the French Army, leading 50,000 men into battle and fighting alongside Napoleon in Italy and Egypt. Josephine and her husband were pledged to be godparents of his firstborn son. Dumas’ second incarnation was serving as the inspiration for the character Edmond Dantès in “The Count of Monte Cristo,” the adventure novel written by his son, the infinitely more famous Alexandre Dumas.

If there is a soupçon of difference in drama between the flesh-and-blood hero and the literary version, it is vanishingly slim. The real Count (his father was a Marquis) was born in 1762 in Jérémie, Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) to a down-and-out French nobleman on the lam and his slave mistress. His first 12 years were relatively carefree. Dumas roamed the countryside around his father’s modest farm in this backwater of Haiti, which Reiss described as “the mulatto capital of the Western world.” Mixed-race offspring could be freemen and society at the highest levels was quite diverse.

But when push came to shove, and his father needed cash to return to France to reclaim his estate, Dumas was sold – actually, pawned is more accurate – into slavery in Port-au-Prince. The father would reclaim him two years later (but not his three siblings, whom he also had sold into slavery). Once a teenager in France, Dumas was treated like a true son, and began an ambitious regimen of education in the literary and military arts. But he never forgave his father and took his name from his mother.

Reiss has written a remarkable and almost compulsively researched account of a man who played a critical, if largely overlooked, role in the French Revolution. The author, who also has been published in The New Yorker and The New York Times, spent a decade on the case, and it shows. The reader gets to know not only Dumas in all his glory but also colonial Haiti, revolutionary France, feudal Italy, and barely medieval Egypt in the bargain. Reiss toured the dungeon where Dumas languished. He spent two years questing after a statue of the hero that once graced the Place Malesherbes in Paris (the Nazis, it turns out, melted it down during World War II). He visited the Musée Alexandre Dumas in Villers-Cotterêts, France (devoted primarily to Dumas the novelist), where he engaged a safecracker to open a long-neglected cache of the General’s letters.

The context of Dumas’ phenomenal career path is painted in rich detail. Despite being financially dependent on an extensive West Indian slave empire (Haiti was the richest colony in the world during the second half of the 18th century), France took the lead in proclaiming human rights, well ahead of Great Britain and the United States. Slavery throughout the empire was abolished in 1794, and people of color in France enjoyed full rights of citizenship, at least for a time.

Napoleon’s rise to power would reverse this truly revolutionary trend, and Dumas would be swept up in the avalanche of racial backsliding. The Black Count’s commanding presence alone, never mind his accomplishments, were a living rebuke to the prevailing racial theories of that and later times. Seeing the tall and confident Dumas standing next to the diminutive Napoleon, Egyptians assumed the former was the leader of the French forces. This didn’t bode well for the subordinate’s career. When his next son was born, Dumas looked elsewhere for godparents.

If nitpicking such a diligent and engaging effort must be made, it is that the context sometimes is a bit too much, distracting from the narrative here and there, noteworthy perhaps only because the reader wants to get back to the rattling good tale. The political machinations of southern Italy circa 1800 are dizzying. There are also points of omission which are not explained (and which may have a perfectly obvious explanation): what, for example, were young Dumas’ two years of non-familial slavery like in Haiti? If Reiss knows, he doesn’t let on; if no documentation exists for this critical period, the reader needs to know.

Otherwise, delve in. The Black Count is no longer languishing in the shrouded corners of fickle history.