Murder Most Archaic

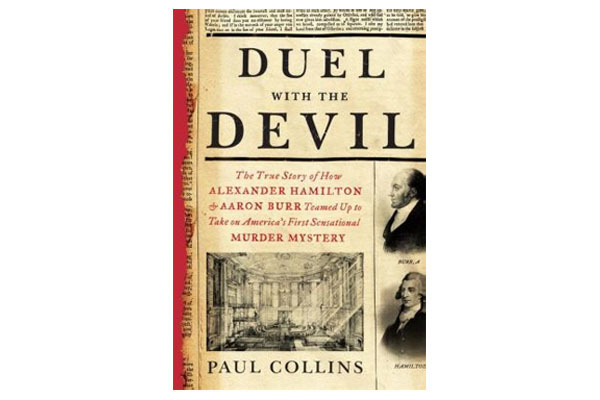

Forget about that fictitious dog that didn’t bark. In "Duel with the Devil" Paul Collins serves up a historical “who done it” that will try your powers of deduction.

Who killed the fetching young Quaker woman is anything but elementary, my dear readers. This engrossing tale boasts the one-horse sleigh which doesn’t jingle, things that go bump in the night, and tantalizingly thin boardinghouse walls. And there is no shortage of suspects.

What more can one ask of a murder mystery, set in New York City circa 1800, the first truly tabloid crime in our nation's history? Well, for good measure, stir in two founding fathers, Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton (who detested one another), and a future Supreme Court Judge (Henry Brockholst Livingston): they formed the legal Dream Team defending the alleged killer.

The defendant needed all three: The whole city thinks he done it. But this is more than simply a good detective story. The book is as much about the time and the place and the people as it is about a devilishly twisted plot.

When Elma Sands, disappears on a late December night in 1799, suspicion quickly falls on Levi Weeks, a fellow boardinghouse resident whose lacerated knee recently had been tenderly tended to by the now missing miss. When she is found dead at the bottom of a well, suspicion turns to certainty.

The rumors that the young couple left together that fateful night and that they recently were betrothed were enough for the man and woman in the street. In those rough and ready times, Weeks’ life would have been in serious jeopardy had he not been arrested, jailed, and charged, on sheer speculation, with the murder. There was no evidence to speak of, nor, for that matter, even any absolute certainty that a homicide had been committed. But back then, it was arrest first, ask questions later.

Enter the legal glitterati: Hamilton, Burr, and Livingston, three of the best lawyers not just in lower Manhattan but perhaps in all the land. The first two were heavily indebted to Week’s brother Ezra, a wealthy and well connected contractor, and they would work the case gratis.

The trio didn’t disappoint, especially Burr, who would spring a classic ambuscade on one of the key prosecution witnesses, the purported gentleman who ran the boardinghouse where Weeks and Sands lived. Yes, he confessed warily, the walls between his establishment and its neighbor were astonishingly thin. He would regret this candid testimony soon enough.

In his eighth book, the author, who is a professor of creative nonfiction and a regular guest on NPR, where he is known as a "literary detective", does not merely purvey murder most archaic. He places the reader in his personal “Way Back Machine” so one can see, feel, and smell how things were when America was still wet behind the ears, Greenwich Village was the sticks, and yellow fever stalked lower Manhattan like the Devil himself.

The War for Independence was nearly 20 years distant, but New York City was just getting back to normal in 1800. Collins writes: “Great swaths of the city had been destroyed by fire in the Revolutionary War, and what wasn’t burned out of spite was burned for survival. When he reconnoitered the British occupied island in 1781, George Washington found it ‘totally stripped of trees,’ with the old woods and orchards chopped down…. It was only now, a generation later that the city had truly recovered.”

On the legal front, practices had steadily been advancing during the 18th century, but they still had a ways to go; and the state of scientific knowledge was decidedly spotty. Malaria was thought by many to be caused by miasma rising from wetlands and to dissolve these pernicious vapors residents regularly fired muskets and even cannons into the gloom. A surer prevention, however, was to head for the hills and many that could would. Fully one third of Manhattan’s 60,000 residents fled during high summer and early fall.

On the lighter side, the diligence of the legal process 200-plus years ago is decidedly charming. For two straight nights the trial went into the wee hours, marathon sessions whose goal was thorough but speedy justice. When it was finally time for the jury to deliberate, the charge from the judge was surprising: He told the jurors not only what he thought their verdict should be, but he threw in the opinion of the mayor as well.

After teaming up in this instance, Hamilton and Burr would, four years hence, be involved in another and far more personal murder case, when Burr gunned down Hamilton in a duel in Weehawken, N. J. Hamilton is thought to have given away his shot in hopes that Burr would miss and both would survive. Burr still holds the singular distinction of being the only U.S. vice president to hold the office while under indictment for murder.

Clearly, truth is often more astonishing than fiction.