Nora Ephron

It almost would be easier to list the things that Nora Ephron didn’t do — and the famous people she didn’t know — than the other way round. Before she died in 2012 at the age of 71, she wrote screenplays, including When Harry Met Sally… and Silkwood. She wrote best-selling books such as I Feel Bad About My Neck and directed the hit movies Sleepless in Seattle and Julie & Julia.

Ephron also was a reporter, producer, essayist, schmoozer, gossip, gourmand, and critic. She wrote about her breasts, about aging, about sex. She hung out with Meryl Streep, Steven Spielberg, Steve Martin, Tom Hanks and myriad other glitterati, and tooted about on David Geffen’s ginormous yacht. Eventually it would be more accurate to say such people hung out with her. She was a force of nature.

Ephron threw A-list dinner parties and was the toast of whatever town she happened to be in, whether New York, Washington, Beverly Hills or the Hamptons. She was a feminist and a foodie, an accomplished cook who ate like a bird, a fast friend but dangerous when crossed. Words were her weapons and she knew how to deploy them.

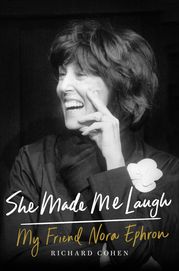

"She Made Me Laugh: My Friend Nora Ephron" (Simon & Schuster, 282 pp., **½ out of four stars) by Richard Cohen, a Washington Post columnist, is not a formal biography but rather a breezy and very personal remembrance of her life and loves, her ups and downs. The two met in 1968 because they shared a mutual friend, Watergate sleuth Carl Bernstein, who would become the second of Ephron’s three husbands and the father of her two children.

Not surprisingly, Cohen writes nice things about his friend, but not always. He found Heartburn, her novel that became a movie starring Jack Nicholson and Streep, to be one toke over the line. The thinly fictionalized account of her unhappy marriage to the unfaithful Bernstein savaged her ex. Cohen criticizes Ephron, who got her start as a journalist, for a biased rendering: “She wrote the history of their marriage, but she did not tell it all.”

Indeed, Ephron often was unkind in print to people who had done her no harm as well as a few, like New York Post publisher Dorothy Schiff, who had done her a solid. In describing the tone and substance of her 1972 Esquire piece on her 10th Wellesley College reunion, Cohen writes that it “reeked of condescension,” adding: “(her classmates) had taken their husbands’ names. She had taken the world by storm.”

Cohen provides proper context for Ephron’s times and trials, and he writes engagingly when he isn’t being too clever by half. The reader grows weary of learning, for example, how Ephron and her posse dined on truffle sandwiches in Nice or imbibed Château d'Yquem, “a celebrated sauterne with the retail value of a nice car.”

As might be expected, Ephron’s good friend leaves things out, such as how she figured out that Mark Felt was Deep Throat, the Watergate source whose identity her ex and Bob Woodward were keeping secret. By her own account, she did all she could to spill the beans, to no avail. Felt was finally outed by his family in 2005.