Operation Vengeance

Next to Adolph Hitler, he was the most infamous man on the planet during World War II. For Americans, it was personal. He had been responsible for the deaths of more than 2,400 U.S. service men and women in little more than two terrifying hours on December 7, 1941. He was the face of duplicity and arrogance, the poster boy for wartime propaganda in the Pacific theater.

Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto was the Osama bin Laden of his day.

So in April 1943 – 16 months after the attack on Pearl Harbor – when the U.S. Army Air Force had an opportunity, however steep the odds, to launch a stealthy attack on Yamamoto, the brass jumped at the chance.

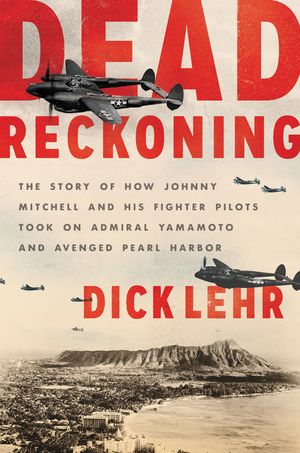

“Dead Reckoning: The Story of How Johnny Mitchell and his Fighter Pilots Took on Admiral Yamamoto and Avenged Pearl Harbor” (Harper, 416 pp., ★★★½ out of four) tells this white-knuckle tale and sheds new light on an important, albeit little-remembered turning point in the war.

While the book's title gives the ending away, author Dick Lehr, a professor of journalism at Boston University, maintains palpable tension throughout. It is a surpassingly improbable feat that these young Americans flyboys accomplished, led by ace pilot and mission planner Major Johnny Mitchell.

The drama is set in another time of sky-high anxiety, when the world was even more topsy-turvy than it is today, having careened without respite from the Great Depression to the most terrible war in human history. The action – including the crucial battle to hold Guadalcanal, the launching pad for Operation Vengeance – unfolds as the reader gets to know the two main protagonists, Mitchell and Yamamoto.

One key to elevating the ambitious American from rural Mississippi to his proper role at center stage of the story is a trove of letters that the author obtained from Mitchell’s family, including those between Mitchell and his young bride, Annie Lee.

These often poignant missives are balanced by correspondence already in the public record between Yamamoto, who was married with children, and his longtime mistress, who was a geisha. The author artfully weaves this compelling human element into the narrative.

The admiral may not have been much of a family man, but he was far from the cartoonish caricature depicted in wartime propaganda. He was a brilliant strategist and leader to be sure, but he also was on the outs with the militarists who came to dominate the Japanese government in the 1930s. He opposed his country’s invasion of China as well as the 1940 Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy – the latter because he correctly anticipated that it would lead to war with the United States, which he also argued against.

Having spent considerable time traveling throughout America – including a stint as naval attaché in Washington D.C. and as a student at Harvard – Yamamoto believed, correctly again, that war with America would be a long shot at best. Without a powerful sucker punch like Pearl Harbor, there would be no chance of winning or forcing an acceptable peace.

If Yamamoto’s arguments had won the day – as opposed to earning him assassination threats from pro-war extremists – there would have been no Pearl Harbor.

Yet in spite of his reservations, Yamamoto, like Johnny Mitchell, was a patriot. They would do their duty, and do it exceedingly well, regardless of the costs.

Yamamoto’s importance to his country’s war effort and morale was evident: Japan delayed announcing his death for a more than a month. Americans remained mum as well, not wanting to reveal the role that breaking the Japanese code had played in his demise.

After a well-earned respite stateside, Major Mitchell would return to action in the Pacific theater. He continued to serve his country, including flying more than 110 combat missions during the Korean War, until his retirement in 1958.