Rick Bragg's South

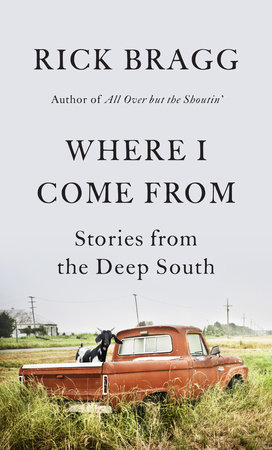

Rick Bragg has a complicated relationship with the American South, where he was born and raised, and which he left for a spell. Even when he was away, he longed to be back home again. Now he is in his ninth book, “Where I Come From: Stories from the Deep South” (Knopf, 256 pp., ★★★½ out of four).

He dearly loves his native Alabama and environs, the bona fide parts, and he writes mostly about these: his family, local legends, indigenous food, personal foibles and southern shenanigans. He’s a son of the southland who isn’t much of a coon hunter or fisherman. Once, he cast and hooked a goat named Ramrod.

He has no use for the rebel flag, or cotillions or swaths of the “new” South populated by “posers” off gassing clichés.

Of his aunt Jo he writes, “She was not the South of meanness and small-mindedness, not the political South that yearns to turn back time.”

On his travels elsewhere, the author picked up some bad habits. Upon one return, his older brother Sam, who never left, is watching him as he opens the trunk of his car. Sam asks, pointing an accusing finger, “What’s that?”

“They’re golf clubs,” replies younger brother, in shame.

“Where I Come From" consists of short pieces, mostly two-pagers, eclectic nuggets about places and people he knows well. He writes about women sporting “kitchen-sink permanents” and men who still carry pocket knives and can fix water pumps. He laments the passing of the steel guitar (among other trends) in country music.

He visits with Harper Lee and Jerry Lee Lewis and pens a paean to Pat Conroy, a friend and fellow southern writer who passed away in 2016. He writes about his affair with Tupperware — while acknowledging that his mother preferred old margarine tubs and thought “Tupperware was just showing off.”

There are longer pieces throughout, and almost all of the chapters are credited to columns published in Southern Living magazine. The former Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist for The New York Times is now a regular contributor to Garden & Gun magazine. It makes perfect sense.

The larger slices of southern life are the most welcome (the reader often is still hungry when the tidbits end). “Jubilee” is an eye-popping eight-pager about a rare natural phenomenon in Mobile Bay, when, for an hour or less in the summer, fish, crabs and eels swarm the shallows like a benign Biblical plague, apparently trying to escape their watery home. When the call goes out, the locals rush to shore, clad in whatever they have on at the time, rods and whatnot in hand. Some of the writhing bounty can simply be scooped up in five-gallon buckets. Without even trying, Bragg explains why it is humans came to believe in miracles.

Rick Bragg is an imperfect man who wishes at times that he and the rest of us could be better than we are. What he writes about “To Kill a Mockingbird” is telling: “[It] was a kind of gospel, north and south, appealing, through the beauty of the story, for us to be better than we were, to live up to our finer natures, and not our baser ones, to rise inside our own consciences and not wallow in the mob.”