The Amazing Mr. Mays

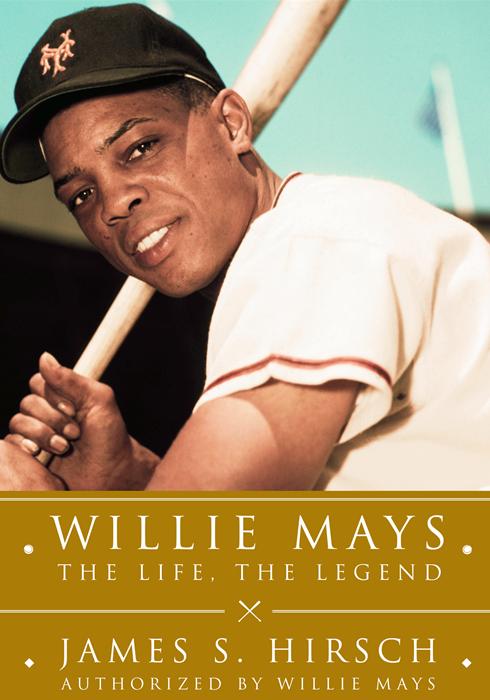

If biases be told, this reviewer is a lifelong Willie Mays fan who can’t imagine a book about his idol being anything but a must-read. Over the years there have been a number of slap-dash biographies of the greatest baseball player ever to lace up spikes, though none recently, and none that have stood the test of time. "Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend" by James S. Hirsch, is long overdue, not only because it brings Willie Mays into sharp focus, but also for documenting, in broad strokes and in intimate details, the evolving times during which the “Say Hey Kid” ruled the diamond – and the hearts of millions of Americans – from his kingdom in center field.

Willie Mays made his mark in four decades, and his career touched all the bases to a degree that only a handful of baseball players can claim. He got his professional start at age 15 in the gritty industrial leagues of Birmingham, Ala. He even played ball with white kids in the neighborhood until grown-ups called the police.

He graduated to the Negro Leagues in the late 1940s, and made the jump to the minors in Trenton, N.J., where he was the only black player in the league in 1950. He had just turned 19. The next spring, he was called up by the New York Giants, who were the runts of the city’s three-team litter. Mays became Rookie of the Year, and the Giants caught the Brooklyn Dodgers to win the National League pennant. In 1954, his first full season in the big leagues (he was in the Army the previous two), Mays was the league’s Most Valuable Player, his team won the World Series, and he made the cover of Time magazine. He was 23.

After his early minor and major league seasons, Mays kept right on playing through the winter, barnstorming the country with black and white all-stars, an activity that would soon fade into history. He slept in segregated hotels, South and North, apart from his white teammates, and when barnstorming disappeared, he played winter ball throughout the Caribbean.

So how good was Willie Mays? He was unlike anything baseball had seen before, or since. He could run like Ty Cobb, field like Joe DiMaggio (only better), hit for power like Babe Ruth, make catches and throws that left his peers shaking their heads in disbelief, swearing that they had never even seen anything to compare it to. He stole bases like a whirlwind, terrifying pitchers, catchers, and fielders alike. He scored from first on a bunt once and could score from second on a ground out. He owned the base paths.

In a game of numbers, he was always better than the box score. Of his over-the-shoulder catch in the 1954 World Series, widely considered to be the greatest catch ever made, Mays insists that he had it all the way, that he was already thinking about the throw well before the ball nestled in his mitt. He was nearly 500 feet from home plate, in the Siberia that was center field in the Polo Grounds, and he wanted to prevent the man at second base from tagging up and scoring. His back to the plate, he caught the ball and spun like a ballerina, throwing in one fluid motion as if he had choreographed it, which he had. The man stayed at third. The Greatest Catch of All Time wasn’t even his best. That’s how good Willie Mays was at our national pastime.

Style was another measure of the man. Willie played the game with a flair, joy, and aggression that was the great legacy of the Negro Leagues. He understood that baseball was entertainment. His hat would fly off as he rounded the bases or made an improbable catch. He played the outfield as if he were an infielder. He gobbled up fly balls (7,095 of them, more than anyone ever) with his patented “basket catch.” No one did it that way, before or since. He threw behind runners (no one does that anymore), decoyed outfielders into thinking they could throw him out so a teammate could advance a base. He did all this and more while looking like he was having the time of his life.

For all his talents and high spirits, Willie took the game to heart. When lesser superstars were playing cards or nursing hangovers before games, Mays, who didn’t drink or smoke, would be talking to the starting hurler about how he should pitch to the opposing lineup. At times he played so hard he would collapse from exhaustion and be taken to the hospital.

Willie wasn’t good at everything. He hasn’t always been adept at handling personal and professional relationships, or money. Part of what made him so endearing, if clearly naive, was that he signed his early contracts without bothering to check the amount. Some black players, like Jackie Robinson, felt he should be more outspoken about racial injustices. When the Giants moved to San Francisco, Willie and his wife had trouble buying a house with cash. He was called every name in the book from the bleachers early on. His response was to play harder. Soon enough the cheers drowned out the jeers. Dodger fans, in Brooklyn and Los Angeles, cheered for him. That’s how good Willie Mays was.

What Willie Mays has done to combat racism is hard to quantify. He was a living rebuke to the notion that whites were superior, that black Americans were to be avoided, relegated to ghettos, kept out of the mainstream. In 1954 the city of Birmingham proclaimed a “Willie Mays Day,” but the festivities were called off at the last moment by police commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, who would turn fire hoses and dogs on peaceful demonstrators nine years hence. Connor understood what Willie Mays meant for business as usual.

White kids all across America could see that he was someone special, someone they wanted to emulate. When my mother noticed that her last-born of five boys was suddenly walking oddly, she was perplexed. Until we were all in the living room watching the Giants on TV and she saw Willie Mays striding to the plate. It became clear to her then.