Very Spicy Book

When Sarah Lohman describes herself as a “historic gastronomist,” she is being too modest. She is, in addition, an accomplished writer, an intrepid traveler, dogged researcher and pundit. She knows what Americans eat, what our ancestors ate, and why.

In tracing the spicy sagas of eight flavors that most modern consumers take for granted — such as black pepper, vanilla and soy sauce — Lohman’s engaging narrative encompasses a good deal of social and political history as well. She stirs in a soupçon of travelogue for good measure by exploring food destinations, including a Mexican vanilla plantation.

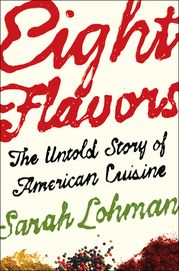

Boiled down to its essence, "Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine" (Simon & Schuster, 229 pp., three and a half stars out of four) is as much about national identity as it is about food. Just as individuals are what they eat, a nation’s evolving food preferences reveal a great deal about its character. And America boasts “the most fascinating and complicated cuisine on the planet,” according to Lohman.

So where did all of our flavorful faves come from? The vast majority migrated here from other places and other people. For example, when Thomas Jefferson was posted in France in the 1780s, he took a shine to the food; he returned home not simply with recipes for decadent delicacies, but also with a French chef in tow.

As she does throughout the book, the author liberally seasons her chapters with recipes — like French vanilla ice cream, exactly as Jefferson copied it down. The reader learns, too, what was cooking in Martha Washington’s kitchen, such as black pepper cookies with a shelf life of six months — yum!

Tastes often changed when Americans went off to war. After invading and defeating Mexico in the 1840s, soldiers returned home craving spicy bowls of chili. Texans, including a German immigrant who invented chili powder, capitalized on this novel flavor and helped to spread it far and wide.

Garlic was a bit player in domestic fare until waves of Italian immigrants arrived in the late 19th and early 20th century. Initially, the pungent plant was viewed as alien and off-putting, the peculiar province of “foreigners.” Today, garlic is “used more frequently in American food than any other flavor in this book,” Lohman writes.

While foreign dishes were welcomed heartily, the foreigners who introduced them often were not. In telling the tale of Prince Ranji Smile, the author tackles immigration policy. Smile arrived from India at the dawn of the 20th century and popularized curry dishes from his homeland. He was America’s first celebrity chef. The 1921 Fannie Farmer Cookbook contained 20 recipes that required curry powder. But a 1923 U.S. Supreme Court decision denied citizenship to Indian nationals like Smile, including those who previously had obtained it.

Lohman serves up more than history and recipes. She delves into the chemical minutiae of flavors and how genetics, culture and even mother’s milk affect food choices. Most of all, she writes with passion and insight, if occasional hyperbole: “In America, we have an infinite number of national identities — but these eight flavors are common to all of us.”