Sitting Bull

in 1872, despite repeated warnings from the Lakota Sioux tribes, white people came into the valley of the Yellowstone River to plan their railroad through the as yet unceded Indian territory. The iron track would connect St. Paul, Minn. and Seattle, Wash., splitting the northern Great Plains, in what is now Montana, like a knife.

The Sioux tribes, led by Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and others, vowed to fight and they did. The whites had already pushed them west. Their people had migrated from Minnesota to hunt buffalo astride the horses brought to their land by the white tribe. Now there was nowhere else to go.

Sitting Bull and his band, the Hunkpapas, had been skirmishing with whites and their soldiers for a decade, and the killing would continue for nearly 10 more years, including the momentous battle of Little Big Horn. By 1980 Sitting Bull was the most famous of all Native Americans, one of the last irreconcilables, the man who had masterminded the death of Gen. George Armstrong Custer and 262 of his men in the Seventh Cavalry in 1876, America's centennial year.

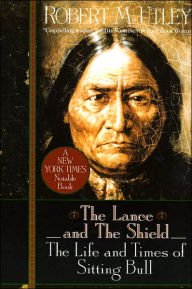

In "The Lance and the Shield: The Life and Times of Sitting Bull," Robert Utley rises to the challenge of writing a biography of a man who hadn't left much of a paper trail. It is full of vivid detail and drama.

For example, during an otherwise unremarkable August 1872 scuffle between the Sioux and a U.S. Army command escorting railway engineers (one soldier and two warriors died), Sitting Bull decided it was a good time for a smoke. With pipe and tobacco pouch, he walked within view and range of the Army rifles and calmly sat down to puff away. Four others, including his nephew While Bull, nervously joined him.

As bullets zipped past or kicked up the sand about them, the four passed the pipe. When the tobacco burned out, Sitting Bull cleaned the bowl, placed the pipe back in his pouch and slowly walked back to his warriors and safety.

Already a showman (later, in 1885 he would star in Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show), Sitting Bull was sending a message to both sides in the battle for the last Sioux homeland: I am unafraid and ready to die; I would rather be red and dead than white and all right.

After his eventual surrender in 1881 - when no safe refuge remained and there were no more buffalo to feed his people - and after he had seen the marvels of the white tribe, Sitting Bull remained convinced that the old ways of his people, however irretrievable, were superior. He said: "The life of the white men is slavery. They are prisoners in towns and farms. The life my people want is the life of freedom. I have seen nothing that a white man has, houses or railways or clothing or food, that is as good as the right to move in the open country, and live in our own fashion."

To a U.S. government bent upon turning "wild" Indians into carbon copies of "civilized" whites, such talk was disquieting. And though he farmed and sent his children to reservation schools, Sitting Bull ever remained irreconcilable. Rather than pray to the Christian God, he helped foment the traditional spiritual practice known as the "Ghost Dance," with it messianic prophecy of kingdom come and the eternal damnation of the white race.

For exercising his freedom to worship, the Hunkpapa chief would die in 1890 in a botched attempt to arrest him. The bullets were fired not by whites but by Indian reservation police, fellow Sioux, including some whom he had led in battle.

In his latest book on the Sioux and how the West was lost, Utley, a former chief historian of the National Park Service, does a masterful job. It is not easy to chronicle a man who was not mentioned in print until 1865, when he was 34, or thereabouts.

The author relies on accounts of the chief's surviving kin and tribesmen, gleaned from research of an earlier biographer, as well as reports by journalists, soldiers, and government records. The book is no polemic, although Utley clearly is sympathetic to his subject, whom he terms an "Indian patriot."

If the author can be criticized, it is for being too restrained. He lets Gen. Custer off the hook for helping to stir up the antagonism of Indians toward him and his men. No mention is made of Custer's unprovoked massacre, in 1868, of Cheyenne in Oklahoma, including women and children and more than 600 horses. He mistakenly attacked a peaceful group who actually were living on a government reservation. Surely that was part of Sitting Bull's life and times and his determination to fight on in spite of great odds.

At Little Big Horn Custer was trying mightily to repeat his "triumph" of eight years earlier.